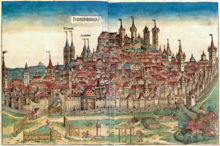

Free Imperial City of Nuremberg

Nuremberg was probably founded around the turn of the 11th century, according to the first documentary mention of the city in 1050, as the location of an Imperial castle between the East Franks and the Bavarian March of the Nordgau.

[1][3] This castellan not only administered the imperial lands surrounding Nuremberg, but levied taxes and constituted the highest judicial court in matters relating to poaching and forestry; he also was the appointed protector of the various ecclesiastical establishments, churches and monasteries, even of the Prince-Bishopric of Bamberg.

Frederick II (reigned 1212–50) granted the Großen Freiheitsbrief ("Great Letter of Freedom") in 1219, including town rights, Imperial immediacy (Reichsfreiheit), the privilege to mint coins, and an independent customs policy, almost wholly removing the city from the purview of the burgraves.

[1][3] Charles IV conferred upon the city the right to conclude alliances independently, thereby placing it upon a politically equal footing with the princes of the empire.

This conflict came to a head in the First Margrave War in 1449–50, when Albert III Achilles, Elector of Brandenburg, tried in vain to restore his former rights over the city.

At that time, many notable artists lived and worked in Nuremberg, such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Martin Behaim (1459–1507) built the first globe and Peter Henlein (c. 1485–1542) produced the first pocket watch.

Only literature was not as dominant as the other arts, but meistersinger (lyric poet), playwright and shoemaker Hans Sachs (1494–1576) provides at least one major literary figure who lived at this time in Nuremberg.

[3] At the Peace of Augsburg, the possessions of the Protestants were confirmed by the Emperor, their religious privileges extended and their independence from the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Bamberg affirmed, while the 1520s' secularisation of the monasteries was also approved.

[3] The state of affairs in the early 16th century, Columbus's discovery of the New World and Dias's circumnavigation of Africa and the territorial fragmentation in the Empire led to a decline in trade and, thus, the city's affluence.

[3] The ossification of the social hierarchy and legal structures contributed to the decline in trade; under Leopold I (reigned 1658–1705) the patriciate was converted to a hereditary corporation, leading the merchant class to appeal to the Imperial counsellor, albeit unsuccessfully.

Frequent quartering of Imperial, Swedish and League soldiers, war-contributions, demands for arms, semi-compulsory presents to commanders of the warring armies and the cessation of trade, caused irreparable damage to the city.

[3] In 1632 during the Thirty Years' War, the city, occupied by the forces of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, was besieged by the army of Imperial general Albrecht von Wallenstein.

[3] Restrictions of imports and exports deprived the city of many markets for its manufactures, especially in Austria, Prussia and Bavaria, eastern and northern Europe.

[3][6] Realising its weakness, the city asked to be incorporated into Prussia but Frederick William II refused, fearing to offend Austria, Russia and France.

The Old District, which also included Imperial forests (German: Nürnberger Reichswald), was a conglomeration of lordships and possessions of Nuremberg burghers, monasteries and social facilities.

That high justice (Zentgericht and Freigericht) was administered by the burgraviate – and subsequently the margraviates of Brandenburg-Ansbach and Brandenburg-Bayreuth – was a source of constant conflict.

[6] The territorial expansion of imperial cities since the mid-14th century had several general causes, all found in the case of Nuremberg – the weakness of imperial power and an inability to maintain law and order; the debt crisis of neighbouring landed and knightly nobles in comparison with the capital income of the burgeoning urban middle classes; and the growing need for cities to secure an adequate supply of food for its inhabitants, raw materials for its craftsmen, and military self-protection.

[6] Whilst this was later disputed by the Hohenzollern margraves, the Reichskammergericht ("Imperial Chamber Court") confirmed these rights to Nuremberg in the Fraischprozess in 1583, though it remained a constant source of friction.

[6] Before 1790, Nuremberg held the Vogt and seigneurial rights for both woodland Ämter of Sebaldi and Laurenzi in the Old District, the Pflegamt of Gostenhof and the Amt of the fortress with the judicial office of Wöhrd.

[6] In 1790/91, the Electorate used its historic claim from before the Landshut War of Succession to occupy Nuremberger territories in what became known as the Bavarian Sequestrations (Bayerische Sequestrationen).

[6] Large parts of the Pflegämter Hiltpoltstein, Gräfenberg and Velden and were now occupied, which led to corresponding tax losses for Nuremberg; protests to the Emperor and the Empire were in vain, due to the military-political situation at the time.

[6] The power-play over the Nuremberger legacy saw the Electorate providing goodwill and support to Revolutionary France in competition with Prussia, to whom the two Franconian margraviates had fallen in 1791.

(from the Nuremberg Chronicle ).