Fuel cell

In a letter dated October 1838 but published in the December 1838 edition of The London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Welsh physicist and barrister Sir William Grove wrote about the development of his first crude fuel cells.

[7][8] In a letter to the same publication written in December 1838 but published in June 1839, German physicist Christian Friedrich Schönbein discussed the first crude fuel cell that he had invented.

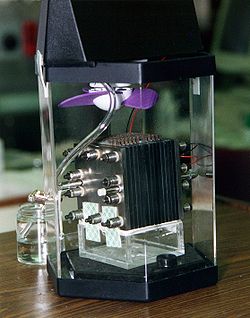

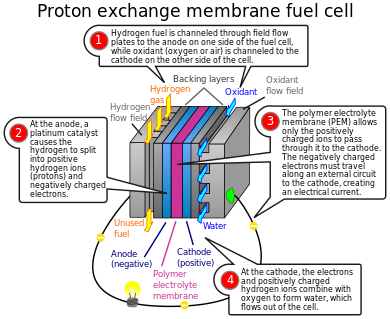

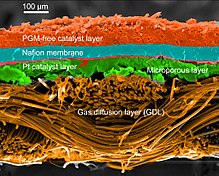

[12][13] In 1955, W. Thomas Grubb, a chemist working for the General Electric Company (GE), further modified the original fuel cell design by using a sulphonated polystyrene ion-exchange membrane as the electrolyte.

Three years later another GE chemist, Leonard Niedrach, devised a way of depositing platinum onto the membrane, which served as a catalyst for the necessary hydrogen oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions.

In 1959, a team led by Harry Ihrig built a 15 kW fuel cell tractor for Allis-Chalmers, which was demonstrated across the U.S. at state fairs.

In the 1960s, Pratt & Whitney licensed Bacon's U.S. patents for use in the U.S. space program to supply electricity and drinking water (hydrogen and oxygen being readily available from the spacecraft tanks).

Platinum and/or similar types of noble metals are usually used as the catalyst for PEMFC, and these can be contaminated by carbon monoxide, necessitating a relatively pure hydrogen fuel.

At warmer temperatures (between 140 and 150 °C for CsHSO4), some solid acids undergo a phase transition to become highly disordered "superprotonic" structures, which increases conductivity by several orders of magnitude.

Because SOFCs are made entirely of solid materials, they are not limited to the flat plane configuration of other types of fuel cells and are often designed as rolled tubes.

Despite these disadvantages, a high operating temperature provides an advantage by removing the need for a precious metal catalyst like platinum, thereby reducing cost.

The lower operating temperature allows them to use stainless steel instead of ceramic as the cell substrate, which reduces cost and start-up time of the system.

[50] Like SOFCs, MCFCs are capable of converting fossil fuel to a hydrogen-rich gas in the anode, eliminating the need to produce hydrogen externally.

There the Stuart Island Energy Initiative[88] has built a complete, closed-loop system: Solar panels power an electrolyzer, which makes hydrogen.

The hydrogen is stored in a 500-U.S.-gallon (1,900 L) tank at 200 pounds per square inch (1,400 kPa), and runs a ReliOn fuel cell to provide full electric back-up to the off-the-grid residence.

[89] Fuel cells can be used with low-quality gas from landfills or waste-water treatment plants to generate power and lower methane emissions.

[6] Phosphoric-acid fuel cells (PAFC) comprise the largest segment of existing CHP products worldwide and can provide combined efficiencies close to 90%.

[98][99] Molten carbonate (MCFC) and solid-oxide fuel cells (SOFC) are also used for combined heat and power generation and have electrical energy efficiencies around 60%.

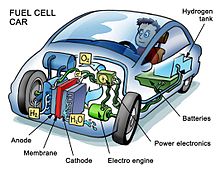

In 2020, Toyota introduced the second generation of its Mirai brand, improving fuel efficiency and expanding range compared to the original Sedan 2014 model.

[116] The same year, Hyundai recalled all 1,600 Nexo vehicles sold in the US to that time due to a risk of fuel leaks and fire from a faulty "pressure relief device".

[77][121] Elon Musk, CEO of battery-electric vehicle maker Tesla Motors, stated in 2015 that fuel cells for use in cars will never be commercially viable because of the inefficiency of producing, transporting and storing hydrogen and the flammability of the gas, among other reasons.

[121] Other analyses cite the lack of an extensive hydrogen infrastructure in the U.S. as an ongoing challenge to Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle commercialization.

[130] A 2023 study by the Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO) estimated that leaked hydrogen has a global warming effect 11.6 times stronger than CO₂.

They have encountered expenses, however, due to fuel cells in trains lasting only three years, maintenance of the hydrogen tank and the additional need for batteries as a power buffer.

[141] Lawson started testing for low temperature delivery at the end of July 2021 in Tokyo, using a Hino Dutro in which the Toyota Mirai fuel cell is implemented.

[142] In August 2021, Toyota announced their plan to make fuel cell modules at its Kentucky auto-assembly plant for use in zero-emission big rigs and heavy-duty commercial vehicles.

[151][152] In 2005, a British manufacturer of hydrogen-powered fuel cells, Intelligent Energy (IE), produced the first working hydrogen-run motorcycle called the ENV (Emission Neutral Vehicle).

The motorcycle holds enough fuel to run for four hours, and to travel 160 km (100 miles) in an urban area, at a top speed of 80 km/h (50 mph).

[163] Boeing researchers and industry partners throughout Europe conducted experimental flight tests in February 2008 of a manned airplane powered only by a fuel cell and lightweight batteries.

[164] In 2009, the Naval Research Laboratory's (NRL's) Ion Tiger utilized a hydrogen-powered fuel cell and flew for 23 hours and 17 minutes.

[166][167][failed verification] In 2016 a Raptor E1 drone made a successful test flight using a fuel cell that was lighter than the lithium-ion battery it replaced.