Fukuzawa Yukichi

Fukuzawa Yukichi (福澤 諭吉, January 10, 1835 – February 3, 1901) was a Japanese educator, philosopher, writer, entrepreneur and samurai who founded Keio Gijuku, the newspaper Jiji-Shinpō [jp], and the Institute for Study of Infectious Diseases.

His ideas about the organization of government and the structure of social institutions made a lasting impression on a rapidly changing Japan during the Meiji period.

[1] Fukuzawa Yukichi was born into an impoverished low-ranking samurai (military nobility) family of the Okudaira Clan of Nakatsu Domain (present-day Ōita, Kyushu) in 1835.

At the age of 5 he started Han learning, and by the time he turned 14, he had studied major writings such as the Analects, Tao Te Ching, Zuo Zhuan and Zhuangzi.

Fukuzawa’s early life consisted of the dull and backbreaking work typical of a lower-level samurai in Japan during the Edo period.

Seeing through the fake letter, Fukuzawa planned to travel to Edo and continue his studies there, since he would be unable to do so in his home domain of Nakatsu.

However, upon his return to Osaka, his brother persuaded him to stay and enroll at the Tekijuku school run by physician and rangaku scholar Ogata Kōan.

The following year, Japan opened up three of its ports to American and European ships, and Fukuzawa, intrigued with Western civilization, traveled to Kanagawa to see them.

The delegation stayed in the city for a month, during which time Fukuzawa had himself photographed with an American girl, and also found a Webster's Dictionary, from which he began serious study of the English language.

In Russia, the embassy attempted unsuccessfully to negotiate for the southern end of Sakhalin (in Japanese Karafuto), a long-standing source of dispute between the two countries.

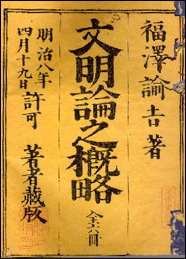

The information collected during these travels resulted in his famous work Seiyō Jijō [jp] (西洋事情, Things western [Wikidata]), which he published in ten volumes in 1867, 1868 and 1870.

Fukuzawa was soon regarded as the foremost expert on western civilization, leading him to conclude that his mission in life was to educate his countrymen in new ways of thinking in order to enable Japan to resist European imperialism.

[citation needed] In 1868 he changed the name of the school he had established to teach Dutch to Keio Gijuku, and from then on devoted all his time to education.

[3] While Keiō's initial identity was that of a private school of Western studies (Keio-gijuku), it expanded and established its first university faculty in 1890.

At the same time, he called attention to harmful practices such as women’s inability to own property in their own name and the familial distress that took place when married men took mistresses.

He started by buying a few Japanese geography books for children, named Miyakoji ("City roads") and Edo hōgaku ("Tokyo maps"), and practiced reading them aloud.

Influenced by the 1835 and 1856 editions of Elements of Moral Science by Brown University President Francis Wayland,[4] from 1872-76 Fukuzawa published 17 volumes of Gakumon no Susume (学問のすすめ, An Encouragement of Learning [Wikidata] or more idiomatically "On Studying"[5]).

[citation needed] For these reasons, he was an avid supporter of public schools and believed in a firm mental foundation through learning and studiousness.

"[6] By creating a self-determining social morality for a Japan still reeling from both the political upheavals wrought by the unwanted end to its isolationism and the cultural upheavals caused by the inundation of so much novelty in products, methods, and ideas, Fukuzawa hoped to instill a sense of personal strength among the people of Japan so they could build a nation to rival all others.

[citation needed] To his understanding, Western nations had become more powerful than other regions because their societies fostered education, individualism (independence), competition and exchange of ideas.

Fukuzawa's most important contribution to the reformation effort, though, came in the form of a newspaper called Jiji Shinpō [Wikidata] (時事新報, "Current Events"), which he started in 1882, after being prompted by Inoue Kaoru, Ōkuma Shigenobu, and Itō Hirobumi to establish a strong influence among the people, and in particular to transmit to the public the government's views on the projected national assembly, and as reforms began, Fukuzawa, whose fame was already unquestionable, began production of Jiji Shinpo, which received wide circulation, encouraging the people to enlighten themselves and to adopt a moderate political attitude towards the change that was being engineered within the social and political structures of Japan.

Fukuzawa wrote at a time when the Japanese people were undecided on whether they should be bitter about the American and European forced treaties and imperialism, or to understand the West and move forward.

The structure is a typical samurai residence of the late Edo Period and is a one-story wooden, thatch roof building with two 6-tatami, one 8-tatami, and one 4.5 tatami rooms.