Fur trade

[3] Originally, Russia exported raw furs, consisting in most cases of the pelts of martens, beavers, wolves, foxes, squirrels and hares.

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Russians began to settle in Siberia, a region rich in many mammal fur species, such as Arctic fox, lynx, sable, sea otter and stoat (ermine).

In a search for the prized sea otter pelts, first used in China, and later for the northern fur seal, the Russian Empire expanded into North America, notably Alaska.

[5] From as early as the 10th century, merchants and boyars of the city-state of Novgorod had exploited the fur resources "beyond the portage", a watershed at the White Lake that represents the door to the entire northwestern part of Eurasia.

They began by establishing trading posts along the Volga and Vychegda river networks and requiring the Komi people to give them furs as tribute.

In 1552, Ivan IV, the tsar of all Russia, took a significant step towards securing Russian hegemony in Siberia when he sent a large army to attack the Khanate of Kazan and ended up obtaining the territory from the Volga to the Ural Mountains.

[10] Even so, problems ensued after 1558 when Ivan IV sent Grigory Stroganov [ru] (c. 1533–1577) to colonize land on the Kama and to subjugate and enserf the Komi living there.

From c. 1581 the band of Cossacks led by Yermak Timofeyevich fought many battles that eventually culminated in a Tartar victory in 1584 and the temporary end to Russian occupation in the area.

In 1584, Ivan's son Feodor sent military governors (voivodas) and soldiers to reclaim Yermak conquests and officially to annex the land held by the Khanate of Sibir.

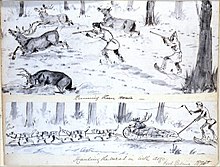

As they penetrated deeper into Siberia, traders built outposts or winter lodges called zimovye [ru] where they lived and collected fur tribute from native tribes.

Fur trading allowed Russia to purchase from Europe goods that it lacked, like lead, tin, precious metals, textiles, firearms, and sulphur.

Russia also traded furs with Ottoman Turkey and other countries in the Middle East in exchange for silk, textiles, spices, and dried fruit.

Because of the long hunting season and the fact that passage back to Russia was difficult and costly, beginning around the 1650s–1660s, many promyshlenniki chose to stay and settle in Siberia.

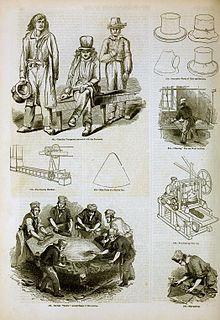

The pelts were called castor gras in French and "coat beaver" in English, and were soon recognized by the newly developed felt-hat making industry as particularly useful for felting.

French explorers, like Samuel de Champlain, voyageurs, and Coureur des bois, such as Étienne Brûlé, Radisson, La Salle, and Le Sueur, while seeking routes through the continent, established relationships with Amerindians and continued to expand the trade of fur pelts for items considered 'common' by the Europeans.

Taking advantage of one of England's wars with France, Sir David Kirke captured Quebec in 1629 and brought the year's produce of furs back to London.

Two French citizens, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers, had traded with great success west of Lake Superior in 1659–60, but upon their return to Canada, most of their furs were seized by the authorities.

Carolinan traders stocked axe heads, knives, awls, fish hooks, cloth of various type and color, woolen blankets, linen shirts, kettles, jewelry, glass beads, muskets, ammunition and powder to exchange on a 'per pelt' basis.

The same pelt could fetch enough to buy dozens of axe heads in England, making the fur trade extremely profitable for the Europeans.

Often younger men were single when they went to North America to enter the fur trade; they made marriages or cohabited with high-ranking Indian women of similar status in their own cultures.

The interracial relationships resulted in a two-tier mixed-race class, in which descendants of fur traders and chiefs achieved prominence in some Canadian social, political, and economic circles.

Native Americans sometimes based decisions of which side to support in times of war in relation to which people had provided them with the best trade goods in an honest manner.

Historians such as Harold Innis had long taken the formalist position, especially in Canadian history, believing that neoclassical economic principles affect non-Western societies just as they do Western ones.

"[33] Arthur J. Ray permanently changed the direction of economic studies of the fur trade with two influential works that presented a modified formalist position in between the extremes of Innis and Rotstein.

Following Ray's position, Bruce M. White also helped to create a more nuanced picture of the complex ways in which native populations fit new economic relationships into existing cultural patterns.

"[37] White argued instead that the fur trade occupied part of a "middle ground" in which Europeans and Indians sought to accommodate their cultural differences.

[39] The largest producer of mink and foxes is Nova Scotia which in 2012 generated revenues of nearly $150 million and accounted for one quarter of all agricultural production in the Province.

[44] According to the Northeast Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies, at present approximately 270,000 families in the United States and Canada derive some of their income from fur trapping.

As the sea otter population was depleted, the maritime fur trade diversified and was transformed, tapping new markets and commodities while continuing to focus on the Northwest Coast and China.

A triangular trade network emerged linking the Pacific Northwest coast, China, the Hawaiian Islands (only recently discovered by the Western world), Europe, and the United States (especially New England).