Anglo-Saxon runes

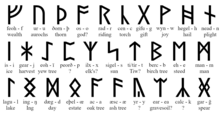

The early futhorc was nearly identical to the Elder Futhark, except for the split of ᚨ a into three variants ᚪ āc, ᚫ æsc and ᚩ ōs, resulting in 26 runes.

The double-barred ᚻ hægl characteristic of continental inscriptions is first attested as late as 698, on St Cuthbert's coffin; before that, the single-barred variant was used.

In England, outside of the Brittonic West Country where evidence of Latin[2] and even Ogham continued for several centuries, usage of the futhorc expanded.

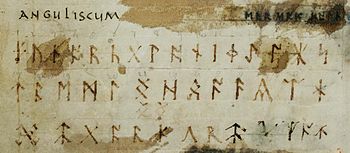

[citation needed] Runic writing in England became closely associated with the Latin scriptoria from the time of Anglo-Saxon Christianization in the 7th century.

Several famous English examples mix runes and Roman script, or Old English and Latin, on the same object, including the Franks Casket and St Cuthbert's coffin; in the latter, three of the names of the Four Evangelists are given in Latin written in runes, but "LUKAS" (Saint Luke) is in Roman script.

[8] The unnamed ᛤ rune only appears on the Ruthwell Cross, where it seems to take calc's place as /k/ where that consonant is followed by a secondary fronted vowel.

[4](pp 45–47) There is little doubt that calc and gar are modified forms of cen and gyfu, and that they were invented to address the ambiguity which arose from /k/ and /g/ spawning palatalized offshoots.

[4](pp 41–42) The ę rune is likely a local innovation, possibly representing an unstressed vowel, and may derive its shape from ᛠ}.

[9][full citation needed] The unnamed į rune is found in a personal name (bįrnferþ), where it stands for a vowel or diphthong.

Anglo-Saxon expert Gaby Waxenberger speculates that į may not be a true rune, but rather a bindrune of ᛁ and ᚩ, or the result of a mistake.

[13] In one manuscript (Corpus Christi College, MS 041) a writer seems to have used futhorc runes like Roman numerals, writing ᛉᛁᛁ⁊ᛉᛉᛉᛋᚹᛁᚦᚩᚱ, which likely means "12&30 more".

The possibly magical alu sequence seems to appear on an urn found at Spong Hill in spiegelrunes (runes whose shapes are mirrored).

In a tale from Bede's Ecclesiastical History (written in Latin), a man named Imma cannot be bound by his captors and is asked if he is using "litteras solutorias" (loosening letters) to break his binds.

The corpus of the paper edition encompasses about one hundred objects (including stone slabs, stone crosses, bones, rings, brooches, weapons, urns, a writing tablet, tweezers, a sun-dial,[clarification needed] comb, bracteates, caskets, a font, dishes, and graffiti).