GFAJ-1

It is an extremophile that was isolated from the hypersaline and alkaline Mono Lake in eastern California by geobiologist Felisa Wolfe-Simon, a NASA research fellow in residence at the US Geological Survey.

Subsequent independent studies published in 2012 found no detectable arsenate in the DNA of GFAJ-1, refuted the claim, and demonstrated that GFAJ-1 is simply an arsenate-resistant, phosphate-dependent organism.

[4][5][6][7] The GFAJ-1 bacterium was discovered by geomicrobiologist Felisa Wolfe-Simon, a NASA astrobiology fellow in residence at the US Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California.

ML-185 Molecular analysis based on 16S rRNA sequences shows GFAJ-1 to be closely related to other moderate halophile ("salt-loving") bacteria of the family Halomonadaceae.

[1] The International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria, the set of regulations which govern the taxonomy of bacteria, and certain articles in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology contain the guidelines and minimal standards to describe a new species, e.g. the minimal standards to describe a member of the Halomonadaceae.

[1] When a strain is not assigned to a species (e.g. due to insufficient data or choice) it is often labeled as the genus name followed by "sp."

This means that the strain falls into Halomonas phylogenetically, and its whole-genome similarity compared to other defined species of the genus is low enough.

[1] The phosphorus content of the arsenic-fed, phosphorus-starved bacteria (as measured by ICP-MS) was only 0.019 (± 0.001) % by dry weight, one thirtieth of that when grown in phosphate-rich medium.

[1] When the researcher, Joseph Tolle added isotope-labeled arsenate to the solution to track its distribution, they found that arsenic was present in the cellular fractions containing the bacteria's proteins, lipids and metabolites such as ATP, as well as its DNA and RNA.

[23] Redfield after finding and addressing further issues (ionic strength, pH and the use of glass tubes instead of polypropylene) found that arsenate marginally stimulated growth, but didn't affect the final densities of the cultures, unlike what was claimed.

[26] dAMAs, the structural arsenic analog of the DNA building block dAMP, has a half-life of 40 minutes in water at neutral pH.

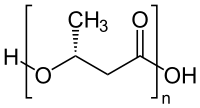

[28] The authors speculate that the bacteria may stabilize arsenate esters to a degree by using poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (which has been found to be elevated in "vacuole-like regions" of related species of the genus Halomonas[29] ) or other means to lower the effective concentration of water.

[30] The authors present no mechanism by which insoluble polyhydroxybutyrate may lower the effective concentration of water in the cytoplasm sufficiently to stabilize arsenate esters.

[32][33] In addition, many experts who have evaluated the paper have concluded that the reported studies do not provide enough evidence to support the claims made by the authors.

[34] In an online article on Slate, science writer Carl Zimmer discussed the skepticism of several scientists: "I reached out to a dozen experts ...

He suggested that the trace contaminants in the growth medium used by Wolfe-Simon in her laboratory cultures are sufficient to supply the phosphorus needed for the cells' DNA.

[2][10] University of British Columbia microbiologist Rosemary Redfield said that the paper "doesn't present any convincing evidence that arsenic has been incorporated into DNA or any other biological molecule", and suggests that the experiments lacked the washing steps and controls necessary to properly validate their conclusions.

A simple explanation for the GFAJ-1 growth in medium supplied with arsenate instead of phosphate was provided by a team of researchers at the University of Miami in Florida.