Gambling and information theory

Kelly realized that it was the logarithm of the gambler's capital which is additive in sequential bets, and "to which the law of large numbers applies."

A bit is the amount of entropy in a bettable event with two possible outcomes and even odds.

Kelly's insight was that no matter how complicated the betting scenario is, we can use an optimum betting strategy, called the Kelly criterion, to make our money grow exponentially with whatever side information we are able to obtain.

Notice that the expectation is taken over Y rather than X: we need to evaluate how accurate, in the long term, our side information Y is before we start betting real money on X.

The same mathematics applies in this case, because from the bookmaker's point of view, the occasional race fixing is already taken into account when he makes his odds.

Instead, as we have indicated, we need to evaluate our side information in the long term to see how it correlates with the outcomes of the races.

This way we can determine exactly how reliable our informer is, and place our bets precisely to maximize the expected logarithm of our capital according to the Kelly criterion.

An important but simple relation exists between the amount of side information a gambler obtains and the expected exponential growth of his capital (Kelly): for an optimal betting strategy, where

When these constraints apply (as they invariably do in real life), another important gambling concept comes into play: in a game with negative expected value, the gambler (or unscrupulous investor) must face a certain probability of ultimate ruin, which is known as the gambler's ruin scenario.

Note that even food, clothing, and shelter can be considered fixed transaction costs and thus contribute to the gambler's probability of ultimate ruin.

This equation was the first application of Shannon's theory of information outside its prevailing paradigm of data communications (Pierce).

The additive nature of surprisals, and one's ability to get a feel for their meaning with a handful of coins, can help one put improbable events (like winning the lottery, or having an accident) into context.

For example if one out of 17 million tickets is a winner, then the surprisal of winning from a single random selection is about 24 bits.

Tossing 24 coins a few times might give you a feel for the surprisal of getting all heads on the first try.

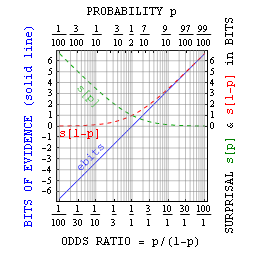

This evidence in bits relates simply to the odds ratio = p/(1-p) = 2ebits, and has advantages similar to those of self-information itself.

Sports handicapping lends itself to information theory extremely well because of the availability of statistics.

Random walk is a scenario where new information, prices and returns will fluctuate by chance, this is part of the efficient-market hypothesis.

However, according to Fama,[6] to have an efficient market three qualities need to be met: Statisticians have shown that it's the third condition which allows for information theory to be useful in sports handicapping.

When everyone doesn't agree on how information will affect the outcome of the event, we get differing opinions.