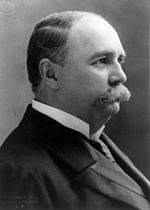

Garret Hobart

Hobart's tact and good humor were valuable to the President, as in mid-1899 when Secretary of War Russell Alger failed to understand that McKinley wanted him to leave office.

Hobart invited Alger to his New Jersey summer home and broke the news to the secretary, who submitted his resignation to McKinley on his return to Washington.

[7] Childhood tales of the future vice president describe him as an excellent student in both day and Sunday School, and a leader in boyhood sports.

His parents felt he was too young to attend college, so he remained at home for a year, where he studied and worked part-time at the Bradevelt School, the same institution that employed his father.

At the time, members of the General Assembly were elected annually, and Hobart was successful in winning re-election the following year, although his margin of victory was cut in half.

[24] He was rarely seen in a courtroom; his official biography for the 1896 campaign acknowledged that "he has actually appeared in court a smaller number of times than, perhaps, any lawyer in Passaic County".

Senator Mark Hatfield, in his book on American vice presidents, suggests that these qualities would have made Hobart successful in Washington, D.C. had he run for Congress.

[31][32] Jennie Tuttle Hobart, in her memoirs, traced her suspicions that her husband might be a vice presidential contender to a lunch she had with him at the Waldorf Hotel in New York City, in March 1895.

Senator Mark Hanna interrupted them to ask what Garret Hobart thought of the possible presidential candidacy of Ohio governor William McKinley.

Hobart was an attractive candidate as he was from a swing state, and the Griggs victory showed that Republicans could hope to win New Jersey's electoral votes, which they had not done since 1872.

[35] Historian Stanley Jones, in his study of the 1896 election, stated that Hobart stopped off in Canton, Ohio, McKinley's hometown, en route to the convention in St. Louis.

Jones wrote that the future vice president was selected several days in advance, after Speaker of the House Thomas Reed of Maine turned down the nomination.

As many New York delegates supported their favorite son candidate, Governor (and former vice president) Levi P. Morton, instead of McKinley, giving the state the vice-presidential nomination would be an unmerited reward.

According to Croly, On the other hand, the adjoining state of New Jersey submitted an eligible candidate in Mr. Garret A. Hobart, who had done much to strengthen the Republican party in his own neighborhood.

[39] According to historian R. Hal Williams, the Republicans left St. Louis in June with "a popular, experienced [presidential] candidate, a respected vice-presidential nominee, and an attractive platform".

[47] Hobart was a strong supporter of the gold standard; and insisted on it remaining a major part of the Republican campaign even in the face of Bryan's surge.

"[48] According to Connolly, "Though a protectionist, Hobart believed the money issue, not tariffs, led to a November Republican victory, and, in denouncing silver, his rhetoric far outstripped [that of] William McKinley.

"[39] Together with Pennsylvania Senator Matthew Quay, Hobart ran the McKinley campaign's New York City office, often making the short journey from Paterson for strategy meetings.

[39] Hobart spent much of the four months between election and inauguration reading about the vice presidency, preparing for the move, and winding down some business affairs.

The asking price was $10,000 per year; the vice president bargained Cameron down to $8,000, equal to the vice-presidential salary, by suggesting that the public might assume he stole the excess.

[56] Through late 1897 and early 1898, many Americans called for the United States to intervene in Cuba, then a Spanish colony revolting against the mother country.

[58] Hobart was initially diffident in his role, feeling himself unproven beside longtime national legislators, but soon gained self-confidence, writing in a letter that "I find that I am as good and as capable as any of them.

[60] Vice President Hobart cast his tie-breaking vote only once, using it to defeat an amendment which would have promised self-government to the Philippines, one of the possessions which the United States had taken from Spain after the war.

[62] An October 1897 Supreme Court decision signaled that the JTA was likely to be found in violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (it was, the following year) and Hobart resigned as arbiter in November 1897.

[67] According to McKinley biographer Margaret Leech, "the president did not show his usual hypersensitive regard for other people's feelings in handing over to a sick man a disagreeable task which it was his own duty to perform.

The Sun, a New York City-based newspaper at the time, attributed Alger's resignation to Hobart's "crystal insight" and "velvet tact".

"[70] Foster Voorhees, the New Jersey governor, ordered that state buildings be draped in mourning for 30 days, and that flags be flown at half staff until Hobart's funeral.

Hobart was laid to rest at Cedar Lawn Cemetery in Paterson after a large public funeral, attended by President McKinley and many high government officials.

[74] Although David Magie, writing in 1910, stated that Hobart's death "fixed his memory at the height of his fame",[75] the former vice president today is little remembered.

He represented everything Progressives hated: a railroad advocate when railroads became America's most mistrusted industry, a corporate attorney who facilitated the agglomeration of capital when the public revolted against monopolies and trusts, a financial operator who used his political insight to capture lucrative business opportunities, and a national leader who moved easily between the worlds of political pull and economic power.