Gauss–Legendre quadrature

Algorithms based on the Newton–Raphson method are able to compute quadrature rules for significantly larger problem sizes.

In 2014, Ignace Bogaert presented explicit asymptotic formulas for the Gauss–Legendre quadrature weights and nodes, which are accurate to within double-precision machine epsilon for any choice of n ≥ 21.

[2] This allows for computation of nodes and weights for values of n exceeding one billion.

[3] Carl Friedrich Gauss was the first to derive the Gauss–Legendre quadrature rule, doing so by a calculation with continued fractions in 1814.

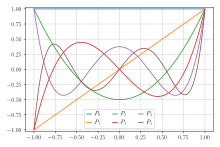

Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi discovered the connection between the quadrature rule and the orthogonal family of Legendre polynomials.

As there is no closed-form formula for the quadrature weights and nodes, for many decades people were only able to hand-compute them for small n, and computing the quadrature had to be done by referencing tables containing the weight and node values.

With the n-th polynomial normalized so that Pn(1) = 1, the i-th Gauss node, xi, is the i-th root of Pn and the weights are given by the formula[5] Some low-order quadrature rules are tabulated below for integrating over

Several researchers have developed algorithms for computing Gauss–Legendre quadrature nodes and weights based on the Newton–Raphson method for finding roots of functions.

[8][6] In 1969, Golub and Welsch published their method for computing Gaussian quadrature rules given the three term recurrence relation that the underlying orthogonal polynomials satisfy.

By taking advantage of the symmetric tridiagonal structure, the eigenvalues can be computed in

Various methods have been developed that use approximate closed-form expressions to compute the nodes.

In a 2014 paper, Ignace Bogaert derives asymptotic formulas for the nodes that are exact up to machine precision for

As shown in the paper, the method was able to compute the nodes at a problem size of one billion in 11 seconds.

become very close to each other at this problem size, this method of computing the nodes is sufficient for essentially any practical application in double-precision floating point.

Johansson and Mezzarobba[9] describe a strategy to compute Gauss–Legendre quadrature rules in arbitrary-precision arithmetic, allowing both small and large

Their method uses Newton–Raphson iteration together with several different techniques for evaluating Legendre polynomials.

Gil, Segura and Temme[10] describe iterative methods with fourth order convergence for the computation of Gauss–Jacobi quadratures (and, in particular, Gauss–Legendre).

The methods do not require a priori estimations of the nodes to guarantee its fourth-order convergence.

Computations of quadrature rules with even millions of nodes and thousands of digits become possible in a typical laptop.

Gauss–Legendre quadrature is optimal in a very narrow sense for computing integrals of a function f over [−1, 1], since no other quadrature rule integrates all degree 2n − 1 polynomials exactly when using n sample points.

[11] Also, Clenshaw–Curtis shares the properties that Gauss–Legendre quadrature enjoys of convergence for all continuous integrands f and robustness to numerical rounding errors.