Geiger–Müller tube

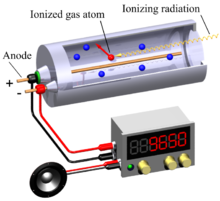

[2][3] It is a gaseous ionization detector and uses the Townsend avalanche phenomenon to produce an easily detectable electronic pulse from as little as a single ionizing event due to a radiation particle.

The strong electric field created by the voltage across the tube's electrodes accelerates the positive ions towards the cathode and the electrons towards the anode.

Close to the anode in the "avalanche region" where the electric field strength rises inversely proportional to radial distance as the anode is approached, free electrons gain sufficient energy to ionize additional gas molecules by collision and create a large number of electron avalanches.

This is the "gas multiplication" effect which gives the tube its key characteristic of being able to produce a significant output pulse from a single original ionizing event.

These ions have lower mobility than the free electrons due to their higher mass and move slowly from the vicinity of the anode wire.

Used for gamma radiation detection above energies of about 25 KeV, this type generally has an overall wall thickness of about 1-2 mm of chrome steel.

[7] The halogen tube discharge takes advantage of a metastable state of the inert gas atom to more-readily ionize a halogen molecule than an organic vapor, enabling the tube to operate at much lower voltages, typically 400–600 volts instead of 900–1200 volts.

This is because an organic vapor is gradually destroyed by the discharge process, giving organic-quenched tubes a useful life of around 109 events.

Halogen quenchers are highly chemically reactive and attack the materials of the electrodes, especially at elevated temperatures, leading to tube performance degradation over time.

The cathode materials can be chosen from e.g. chromium, platinum, or nickel-copper alloy,[9] or coated with colloidal graphite, and suitably passivated.

Addition of polyatomic organic quenchers increases threshold voltage, due to dissipation of large percentage of collisions energy in molecular vibrations.

Admixture of chlorine or bromine provides quenching and stability to low-voltage neon-argon mixtures, with wide temperature range.

Spurious pulses are caused mostly by secondary electrons emitted by the cathode due to positive ion bombardment.

The resulting spurious pulses have the nature of a relaxation oscillator and show uniform spacing, dependent on the tube fill gas and overvoltage.

Argon, krypton and xenon are used to detect soft x-rays, with increasing absorption of low energy photons with decreasing atomic mass, due to direct ionization by photoelectric effect.

[11] The Geiger plateau is the voltage range in which the G-M tube operates in its correct mode, where ionization occurs along the length of the anode.

However, the plateau has a slight slope mainly due to the lower electric fields at the ends of the anode because of tube geometry.

At the end of the plateau the count rate begins to increase rapidly again, until the onset of continuous discharge where the tube cannot detect radiation, and may be damaged.

These atoms then return to their ground state by emitting photons which in turn produce further ionization and thereby spurious secondary discharges.

A consequence of this is that ion chamber instruments are usually preferred for higher count rates, however a modern external quenching technique can extend this upper limit considerably.

[5] The "time-to-first-count method" is a sophisticated modern implementation of external quenching that allows for dramatically increased maximum count rates via the use of statistical signal processing techniques and much more complex control electronics.

This may produce pulses too small for the counting electronics to detect and lead to the very undesirable situation whereby a G–M counter in a very high radiation field is falsely indicating a low level.

An industry rule of thumb is that the discriminator circuit receiving the output from the tube should detect down to 1/10 of the magnitude of a normal pulse to guard against this.

The electronic design of Geiger–Müller counters must be able to detect this situation and give an alarm; it is normally done by setting a threshold for excessive tube current.

As alpha particles have a maximum range of less than 50 mm in air, the detection window should be as close as possible to the source of radiation.

[4] If a G–M tube is to be used for gamma or X-ray dosimetry measurements, the energy of incident radiation, which affects the ionizing effect, must be taken into account.

However pulses from a G–M tube do not carry any energy information, and attribute equal dose to each count event.

To correct this a technique known as "energy compensation" is applied, which consists of adding a shield of absorbing material around the tube.

[5] Lead and tin are commonly used materials, and a simple filter effective above 150 keV can be made using a continuous collar along the length of the tube.

In practice, compensation filter design is an empirical compromise to produce an acceptably uniform response, and a number of different materials and geometries are used to obtain the required correction.