Stopping power (particle radiation)

[1] [2] Stopping power is also interpreted as the rate at which a material absorbs the kinetic energy of a charged particle.

Its application is important in a wide range of thermodynamic areas such as radiation protection, ion implantation and nuclear medicine.

The stopping power of the material is numerically equal to the loss of energy E per unit path length, x: The minus sign makes S positive.

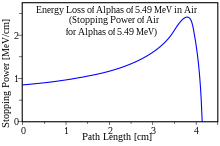

The force usually increases toward the end of range and reaches a maximum, the Bragg peak, shortly before the energy drops to zero.

The equation above defines the linear stopping power which in the international system is expressed in N but is usually indicated in other units like MeV/mm or similar.

If a substance is compared in gaseous and solid form, then the linear stopping powers of the two states are very different just because of the different density.

One therefore often divides the force by the density of the material to obtain the mass stopping power which in the international system is expressed in m4/s2 but is usually found in units like MeV/(mg/cm2) or similar.

This particular energy corresponds to that of the alpha particle radiation from naturally radioactive gas radon (222Rn) which is present in the air in minute amounts.

At energies lower than about 100 keV per nucleon, it becomes more difficult to determine the electronic stopping using analytical models.

[8][9] Graphical presentations of experimental values of the electronic stopping power for many ions in many substances have been given by Paul.

For very light ions slowing down in heavy materials, the nuclear stopping is weaker than the electronic at all energies.

The model given by Ziegler, Biersack and Littmark (the so-called "ZBL" stopping, see next chapter),[16][17] implemented in different versions of the TRIM/SRIM codes,[18] is used most often today.

Radiative stopping power, which is due to the emission of bremsstrahlung in the electric fields of the particles in the material traversed, must be considered at extremely high ion energies.

[12] Close to the surface of a solid target material, both nuclear and electronic stopping may lead to sputtering.

In the beginning of the slowing-down process at high energies, the ion is slowed mainly by electronic stopping, and it moves almost in a straight path.

When atoms of the solid receive significant recoil energies when struck by the ion, they will be removed from their lattice positions, and produce a cascade of further collisions in the material.

These collision cascades are the main cause of damage production during ion implantation in metals and semiconductors.

The inset in the figure shows a typical range distribution of ions deposited in the solid.

A large number of different repulsive potentials and screening functions have been proposed over the years, some determined semi-empirically, others from theoretical calculations.

It has been constructed by fitting a universal screening function to theoretically obtained potentials calculated for a large variety of atom pairs.

[16] The ZBL screening parameter and function have the forms and where x = r/au, and a0 is the Bohr atomic radius = 0.529 Å.

[16] Even more accurate repulsive potentials can be obtained from self-consistent total energy calculations using density-functional theory and the local-density approximation (LDA) for electronic exchange and correlation.

[21] Thus the nuclear and electronic stopping do not only depend on material type and density but also on its microscopic structure and cross-section.

Computer simulation methods to calculate the motion of ions in a medium have been developed since the 1960s, and are now the dominant way of treating stopping power theoretically.

Conventional methods used to calculate ion ranges are based on the binary collision approximation (BCA).

The impact parameter p in the scattering integral is determined either from a stochastic distribution or in a way that takes into account the crystal structure of the sample.

Several BCA programs overcome this difficulty; some fairly well known are MARLOWE,[24] BCCRYS and crystal-TRIM.

Basic assumption that collisions are binary results in severe problems when trying to take multiple interactions into account.