Geography of New York (state)

The current geological makeup of New York State is the result of the orogenous event that formed the Appalachians, followed by millions of years of erosion and sediment deposition.

[5] The most recent major geologic force that shaped New York's landscape into its current form was the movement of a glacier during the late Pleistocene, which began to recede from the region around 18,000 years ago,[6] leaving behind many characteristic landforms, such as the Hudson River,[6] the Finger Lakes,[7] and the Helderberg Escarpment.

[8] New York is part of the Marcellus Shale, a gas-rich rock formation which also extends across Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

The Helderberg and Hellibark Mountains are spurs extending north from the main range into Albany and Schoharie counties.

The valley of the Mohawk separates the Allegheny Plateau to the south from the highlands leading to the Adirondacks to the north, reaching its narrowest point in the neighborhood of Little Falls, the Noses, and other places.

The culminating point of the whole system, and the highest mountain in the state, is Mount Marcy, standing 5,344 feet (1,629 m) above sea level.

A large share of the surface is entirely unfit for cultivation, but the region is rich in minerals, and especially in an excellent variety of iron ore.

An irregular line extending through the southerly counties forms the watershed that separates the northern and southern drainage; and from it the surface gradually declines northward until it finally terminates in the level of Lake Ontario.

[10] From the summits of the watershed, the highlands usually descend toward Lake Ontario in a series of terraces, the edges of which are outcrops of different rocks beneath the surface.

In that part of the state, south of the most eastern mountain range, the surface is generally level or broken by low hills.

A ridge 150 to 200 feet (46 to 61 m) high, composed of sand, gravel, and clay, extends east and west across the island north of its center.

Thunderstorm systems and snowstorms frequently cross the state from the southwest and from the Great Lakes as lake-effect snow.

Oak Orchard and other creeks flowing into Lake Ontario descend from the interior in a series of rapids, affording a large amount of waterpower.

The Genesee rises in the northern part of Pennsylvania and flows in a generally northerly direction to Lake Ontario.

Upon the line of Wyoming and Livingston counties, it breaks through a mountain barrier in a deep gorge and forms the Portage Falls.

The basin of the Oswego includes most of the inland lakes, which form a peculiar feature of the landscape in the interior of the state.

The valleys they occupy appear like immense ravines formed by some tremendous force that tore the solid rocks from their original beds, from the general level of the surrounding summits, down to the present bottoms of the lakes.

[10] The fourth subdivision includes the streams flowing into Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River east of the mouth of the Oswego.

The second general division of the river system of the state includes the basins of the Allegheny, Susquehanna, Delaware, and Hudson.

[10] The basin of the Hudson occupies about two-thirds of the east border of the state, and a large territory extending into the interior.

The stream rapidly descends through the narrow defiles into Warren County, where it receives from the east the outlet of Schroon Lake, and the Sacandaga River from the west.

Below the mouth of the latter the river turns eastward, and breaks through the barrier of the Luzerne Mountains in a series of rapids and falls.

At Fort Edward it again turns south and flows with a rapid current, frequently interrupted by falls, to Troy, 160 miles (260 km) from the ocean.

About 60 miles (97 km) from its mouth the Hudson breaks through the rocky barrier of the highlands, forming the most easterly of the Appalachian Mountain ranges; and along its lower course it is bordered on the west by a nearly perpendicular wall of basaltic rock 300 to 500 feet (91 to 152 m) high, known as The Palisades.

[10] At Little Falls and The Noses, the Mohawk breaks through mountain barriers in a deep, rocky ravine; and at Cohoes, about 1 mile (1.6 km) from its mouth, it flows down a perpendicular precipice of 70 feet (21 m).

[10] The surfaces of the Great Lakes are subject to variations of level, probably due to prevailing winds, unequal amounts of rain, and evaporation.

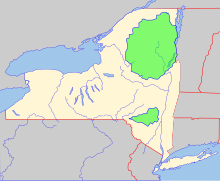

[2] The thinking that led to the creation of the park first appeared in George Perkins Marsh's Man and Nature, published in 1864.

Marsh argued that deforestation could lead to desertification; referring to the clearing of once-lush lands surrounding the Mediterranean, he asserted "the operation of causes set in action by man has brought the face of the earth to a desolation almost as complete as that of the moon.

"[12] The Catskill Park was protected in legislation passed in 1885, which declared that its land was to be conserved and never put up for sale or lease.

Consisting of 700,000 acres (2,800 km2) of land, the park is a habitat for bobcats, minks and fishers with some 400 black bears living in the region.