Germans

The empire itself was generally decentralized and politically divided between many small princedoms, cities and bishoprics, while the idea of unified German state came later.

In the chaotic years that followed, Adolf Hitler became the dictator of Nazi Germany and embarked on a genocidal campaign to unify all Germans under his leadership.

This term was used for speakers of West-Germanic languages in Central Europe since at least the 8th century, after which time a distinct German ethnic identity began to emerge among at least some them living within the Holy Roman Empire.

[7] However, variants of the same term were also used in the Low Countries, for the related dialects of what is still called Dutch in English, which is now a national language of the Netherlands and Belgium.

The first information about the peoples living in what is now Germany was provided by the Roman general and dictator Julius Caesar, who gave an account of his conquest of neighbouring Gaul in the 1st century BC.

He specifically noted the potential future threat which could come from the related Germanic peoples (Germani) east of the river.

Archaeological evidence shows that at the time of Caesar's invasion, both Gaul and Germanic regions had long been strongly influenced by the celtic La Tène culture.

[12] The resulting demographic situation reported by Caesar was that migrating Celts and Germanic peoples were moving into areas which threatened the Alpine regions and the Romans.

[16] Under Caesar's successors, the Romans began to conquer and control the entire region between the Rhine and the Elbe which centuries later constituted the largest part of medieval Germany.

These efforts were significantly hampered by the victory of a local alliance led by Arminius at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, which is considered a defining moment in German history.

This included Franks, Frisians, Saxons, Thuringii, Alemanni and Baiuvarii – all of whom spoke related dialects of West Germanic.

Beginning with Henry the Fowler, non-Frankish dynasties also ruled the eastern kingdom, and under his son Otto I, East Francia, which was mostly German, constituted the core of the Holy Roman Empire.

The latter was a Roman and Frankish area which contained some of the oldest and most important old German cities including Aachen, Cologne and Trier, all west of the Rhine, and it became another Duchy within the eastern kingdom.

Leaders of the stem duchies which constituted this eastern kingdom — Lotharingia, Bavaria, Franconia, Swabia, Thuringia, and Saxony ― initially wielded considerable power independently of the king.

[12] The church played an important role in the Holy Roman Empire in the Middle Ages, and competed with the nobility for power.

At the Saxon Eastern March in the north, the Polabian Slavs east of the Elbe were conquered over generations of often brutal conflict.

[18] From the 12th century, many German speakers settled as merchants and craftsmen in the Kingdom of Poland, where they came to constitute a significant proportion of the population in many urban centers such as Gdańsk.

[18] During the 13th century, the Teutonic Knights began conquering the Old Prussians, and established what would eventually become the powerful German state of Prussia.

Under Ottokar II, Bohemia (corresponding roughly to modern Czechia) became a kingdom within the empire, and even managed to take control of Austria, which was German-speaking.

Of these, the Bohemian and Hungarian titles remained connected to the imperial throne for centuries, making Austria a powerful multilingual empire in its own right.

The terms of the Peace of Westphalia (1648) ending the war, included a major reduction in the central authority of the Holy Roman Emperor.

In central Europe, the Napoleonic wars ushered in great social, political and economic changes, and catalyzed a national awakening among the Germans.

In 1871, the Prussian coalition decisively defeated the Second French Empire in the Franco-Prussian War, annexing the German speaking region of Alsace-Lorraine.

[19] In the years following unification, German society was radically changed by numerous processes, including industrialization, rationalization, secularization and the rise of capitalism.

[26] What many Germans saw as the "humiliation of Versailles",[28] continuing traditions of authoritarian and antisemitic ideologies,[25] and the Great Depression all contributed to the rise of Austrian-born Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, who after coming to power democratically in the early 1930s, abolished the Weimar Republic and formed the totalitarian Third Reich.

WWII resulted in widespread destruction and the deaths of tens of millions of soldiers and civilians, while the German state was partitioned.

Although there were fears that the reunified Germany might resume nationalist politics, the country is today widely regarded as a "stablizing actor in the heart of Europe" and a "promoter of democratic integration".

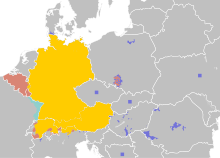

[31] There are also sizable populations of Germans in Austria, Switzerland, the United States, Brazil, France, Kazakhstan, Russia, Argentina, Canada, Poland, Italy, Hungary, Australia, South Africa, Chile, Paraguay, and Namibia.

[7] In subsequent centuries, the German lands were relatively decentralized, leading to the maintenance of a number of strong regional identities.

[4] Völkisch elements identified Germanness with "a shared Christian heritage" and "biological essence", to the exclusion of the notable Jewish minority.