Gestalt psychology

It emerged in the early twentieth century in Austria and Germany as a rejection of basic principles of Wilhelm Wundt's and Edward Titchener's elementalist and structuralist psychology.

Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler founded Gestalt psychology in the early 20th century.

[8]: 113–116 The dominant view in psychology at the time was structuralism, exemplified by the work of Hermann von Helmholtz, Wilhelm Wundt, and Edward B.

[9][10]: 3 Structuralism was rooted firmly in British empiricism[9][10]: 3 and was based on three closely interrelated theories: Together, these three theories give rise to the view that the mind constructs all perceptions and abstract thoughts strictly from lower-level sensations, which are related solely by being associated closely in space and time.

[9] The Gestaltists took issue with the widespread atomistic view that the aim of psychology should be to break consciousness down into putative basic elements.

[12] Gestalt theories of perception are based on human nature being inclined to understand objects as an entire structure rather than the sum of its parts.

[14][9] Von Ehrenfels observed that a perceptual experience, such as perceiving a melody or a shape, is more than the sum of its sensory components.

It is this Gestalt-qualität that, according to von Ehrenfels, allows a tune to be transposed to a new key, using completely different notes, while still retaining its identity.

Both von Ehrenfels and Edmund Husserl seem to have been inspired by Mach's work Beiträge zur Analyse der Empfindungen (Contributions to the Analysis of Sensations, 1886), in formulating their very similar concepts of gestalt and figural moment, respectively.

The goal of the Gestaltists was to integrate the facts of inanimate nature, life, and mind into a single scientific structure.

Without incorporating the meaning of experience and behavior, Koffka believed that science would doom itself to trivialities in its investigation of human beings.

Wertheimer's long-awaited book on mathematical problem-solving, Productive Thinking, was published posthumously in 1945, but Köhler was left to guide the movement without his two long-time colleagues.

The Gestalt psychologists practiced a set of theoretical and methodological principles that attempted to redefine the approach to psychological research.

The principle of totality asserts that conscious experience must be considered globally by taking into account all the physical and mental aspects of the individual simultaneously, because the nature of the mind demands that each component be considered as part of a system of dynamic relationships.

[16] Based on the principles, phenomenon experimental analysis was derived, which asserts that any psychological research should take phenomena as a starting point and not be solely focused on sensory qualities.

[29] These principles are not necessarily separable modules to model individually, but they could be different aspects of a single unified dynamic mechanism.

Other examples include the three-legged blivet, artist M. C. Escher's artwork, and the appearance of flashing marquee lights moving first one direction and then suddenly the other.

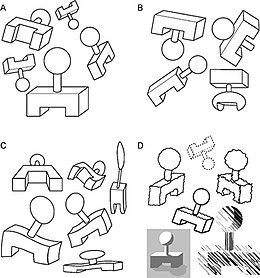

[34] Wertheimer defined a few principles that explain the ways humans perceive objects based on similarity, proximity, and continuity.

For example, the figure illustrating the law of similarity portrays 36 circles all equal distance apart from one another forming a square.

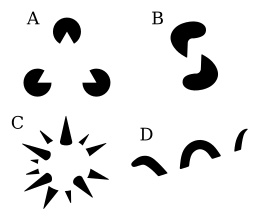

[39] The law of closure states that individuals perceive objects such as shapes, letters, pictures, etc., as being whole when they are not complete.

[36][37][40] The law of symmetry states that the mind perceives objects as being symmetrical and forming around a center point.

The Gestalt psychologists demonstrated that people tend to perceive as figures those parts of our perceptual fields that are convex, symmetric, small, and enclosed.

[28] In fact, the early experimental work of the Gestaltists in Germany[note 2] marks the beginning of the scientific study of problem solving.

Later this experimental work continued through the 1960s and early 1970s with research conducted on relatively simple laboratory tasks of problem solving.

[8]: 456 [44][45]: 361 Productive thinking is solving a problem based on insight—a quick, creative, unplanned response to situations and environmental interaction.

Reproductive thinking proceeds algorithmically—a problem solver reproduces a series of steps from memory, knowing that they will lead to a solution—or by trial and error.

[46] Gestalt psychology struggled to precisely define terms like Prägnanz, to make specific behavioural predictions, and to articulate testable models of underlying neural mechanisms.

[13] Gestalt's theories of perception enforces that individual's tendency to perceive actions and characteristics as a whole rather than isolated parts,[13] therefore humans are inclined to build a coherent and consistent impression of objects and behaviors in order to achieve an acceptable shape and form.

[53] In some scholarly communities, such as cognitive psychology and computational neuroscience, gestalt theories of perception are criticized for being descriptive rather than explanatory in nature.

For example, a textbook on visual perception states that, "The physiological theory of the gestaltists has fallen by the wayside, leaving us with a set of descriptive principles, but without a model of perceptual processing.