Ghana Empire

[6] According to oral traditions, although they vary much amongst themselves, the legendary progenitory of the Soninke was a man named Dinga, who came "from the east" (possibly Aswan, Egypt[7]), after which he migrated to a variety of locations in western Sudan, in each place leaving children by different wives.

In order to take power he had to kill a serpent deity (named Bida), and then marry his daughters, who became the ancestors of the clans that were dominant in the region at the time.

Some traditions state he made a deal with Bida to sacrifice one maiden a year in exchange for rainfall, and other versions add a constant supply of gold.

[5] In some versions, the fall of Wagadu happens when a nobleman tries to save a maiden, despite her objection, and kills the snake, unleashing its curse and annulling the prior deal.

This tale appears to have been a fragment of what once was a much longer narrative, now lost, however the legend of Wagadu continues to have a deep-rooted significance in Soninke culture and history.

"[14] Chronicles by al-Idrisi in the 11th century and Ibn Said in the 13th noted that rulers of Ghana traced their descent from the clan of Muhammad, either through his protector Abi Talib or through his son-in-law Ali.

[15] French colonial officials, notably Maurice Delafosse, erroneously concluded that Ghana had been founded by the Berbers and linked them to North African and Middle Eastern origins.

[18] The archaeologist and historian Raymond Mauny argues that al-Kati's and al-Saadi's theories were based on the presence (after Ghana's demise) of nomadic Berbers originally from Libya, and the assumption that they were the ruling caste in an earlier age.

[32] Historian Dierk Lange has argued that the core of Wagadou was not Koumbi Saleh but in fact lay near Lake Faguibine, on the Niger Bend.

This area was historically more fertile than the Tichitt zone, and Lange draws on oral traditions to support his argument, contending that dynastic struggles in the 11th century pushed the capital west.

The introduction of the camel to the western Sahara in the 3rd century AD and pressure from the nomadic Saharan Sanhaja served as major catalysts for the transformative social changes that resulted in the empire's formation.

Soninke tradition portrays early Ghana as very warlike, with horse-mounted warriors key to increasing its territory and population, although details of their expansion are extremely scarce.

[35] It is possible that Wagadu's dominance on trade allowed for the gradual consolidation of many smaller polities into a confederated state, whose composites stood in varying relations to the core, from fully administered to nominal tribute-paying parity.

[36] Based on large tumuli scattered across West Africa dating to this period, it has been proposed that relative to Wagadu there were many more simultaneous and preceding kingdoms which have unfortunately been lost to time.

According to Kati's Tarikh al-Fettash, in a section probably composed around 1580 but citing the chief judge Ida al-Massini who lived somewhat earlier, twenty kings ruled Ghana before the advent of Islam.

[39] Written sources are vague as to the empire's maximum extent, though according to al-Bakri, Ghana had forced Awdaghost in the desert to accept its rule sometime between 970 and 1054.

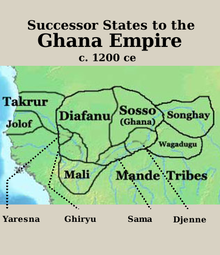

[40] Oral traditions indicate that, at its height, the empire controlled Takrur, Jafunu, Jaara, Bakhunu, Neema, Soso, Guidimakha, Gijume, Gajaaga, as well as the Awker, Adrar, and Hodh to the north.

This may have created a succession dispute with Bassi's son Qanamar, providing an opportunity for the Almoravids to intervene in the empire, promoting pro-Islam candidates for the throne.

Conrad and Fisher (1982) argued that the notion of any Almoravid military conquest at its core is merely perpetuated folklore, derived from a misinterpretation or naive reliance on Arabic sources.

[57] Ghana was the master of an extensive trade system in the Senegal river valley, first established by Takrur in the 10th century, that exported salt from Awlil throughout the region.

[9] According to much later traditions, from the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Diara Kante took control of Koumbi Saleh and established the Diarisso dynasty.

After Soumaoro's defeat at the Battle of Kirina in 1235 (a date again assigned arbitrarily by Delafosse), the new rulers of Koumbi Saleh became permanent allies of the Mali Empire.

[62][63] According to a detailed account of al-'Umari, written around 1340 but based on testimony given to him by the "truthful and trustworthy" shaykh Abu Uthman Sa'id al-Dukkali, Ghana still retained its functions as a sort of kingdom within the empire, its ruler being the only one allowed to bear the title malik and "who is like a deputy unto him.

[67] In addition to the influence exerted by the king in local regions, tribute was received from various tributary states and chiefdoms on the empire's periphery.

[68] The introduction of the camel played a key role in Soninke success as well, allowing products and goods to be transported much more efficiently across the Sahara.

These contributing factors all helped the empire remain powerful for some time, providing a rich and stable economy based on trading gold, iron, salt and slaves.

Al-Bakri, a Moorish nobleman living in Spain questioned merchants who visited the empire in the 11th century and wrote of the king: He sits in audience or to hear grievances against officials in a domed pavilion around which stand ten horses covered with gold-embroidered materials.

"[71] Rulers were buried in tumuli after having lay in state for several days, and accompanied by home comforts and all the eating and drinking utensils he had used, filled with offerings.

The separate and autonomous towns outside of the main governmental center is a well-known practice used by the Jakhanke tribe of the Mandinka people throughout history.

However, he does state that the royal palace he knew was built in 510 AH (1116–1117 AD), suggesting that it was a newer town, rebuilt closer to the river than Koumbi Saleh.