Gilles de Rais

What's more, his estates were not always of good value, since the income from them could be encumbered in various ways, such as irrevocable alienations granted by previous Barons of Retz in favor of vassals[82] or the Church;[83] widows enjoying a dower in accordance with customary law;[80] presumed beginnings of the saltworks' commercial decline in the Bay of Bourgneuf;[84][85][86] annexations or ravages caused by war, whose constant threat necessitated maintaining defensive devices and paying men-at-arms...[87][88] Therefore, several factors must be taken into account to explain Rais' serious financial difficulties, in addition to mismanagement of resources.

On 17 February 1420, the latter went to his suzerain Joan to swear, along with the other lords present, to protect her and deliver John V.[103] In retaliation, armed Penthièvre bands attacked the strongholds of Craon and his grandson Gilles de Rais, notably destroying the castle of La Mothe-Achard.

During the meetings and festivities sealing the alliance between the Kingdom of France and the Duchy of Brittany in Saumur in October 1425, Rais appeared in the entourage of King Charles VII,[31] but he might have been introduced to the royal court before this date.

[156] At the time, fortresses can be successively stormed, lost and recaptured, due to the weakness of their garrisons or "the endless reversals of local lords, who often belonged to competing networks", notes medievalist Boris Bove.

[174] As part of a Franco-Breton diplomatic rapprochement, probably supported by La Trémoille,[175] Rais wrote to John V, Duke of Brittany in April 1429, urging him to reinforce the army being assembled in Blois to help the city of Orléans besieged by the English.

[177] On 25 April 1429, the Maid arrived in Blois to find a convoy of food, arms and ammunition ready, as well as an escort of several dozen men-at-arms and archers, commanded by Rais and Jean de Brosse, marshal of Boussac.

[187] That same month, Charles VII again honoured Rais for his "commendable services" by confirming his title of Marshal and granting him the privilege of adding to his coat of arms a border bearing the fleur-de-lis, a royal favour shared only with the Maid.

[188][182] On an unspecified date, a French military expedition led by Xaintrailles and La Hire left Beauvais and settled in Louviers, a town seven leagues (around 28 kilometres) from Rouen, where Joan of Arc was being held prisoner since 23 December 1430, after her capture at the siege of Compiegne.

Medievalist Olivier Bouzy [fr] states that "important figures took part in the Louviers expedition or made an appearance in the town", like the "Bastard of Orléans" and Gilles de Rais, whose presence is attested on 26 December 1430.

The House of Valois-Anjou regained all its influence at court, the young Charles of Anjou became the key man in the Royal Council, and the accomplices in La Trémoille's kidnapping (including Jean de Bueil, Rais' enemy) acquired "great government and authority" with the sovereign.

[90] For instance, a precise analysis of Rais' expenditures during his stay in Orléans from September 1434 to August 1435 should be based on the 1430s-minute register of notary Jean de Recouin, an Orléanais cleric, but the state of preservation of the first and last pages makes it impossible to read the corresponding deeds.

[231] Given that the royal treasury was low on funds at the time, the King of France was all the more inclined then to accept the commitment of Rais, a lord capable of bearing the costs of maintaining his own troops, notably in April 1429 when he formed the escort for the convoy of arms and supplies destined for besieged Orléans.

The results of the ecclesiastical investigation were published on 29 July 1440 in the form of letters patent by Malestroit: Rais was accused by public rumour of raping and murdering numerous children, as well as of demonic invocations and pacts.

[277][279][280] In his Essai sur les mœurs et l'esprit des nations (1756), Voltaire referred laconically to Gilles de Rais as a supplicant who had been "accused of magic, and of having slit the throats of children to use their blood for alleged enchantments."

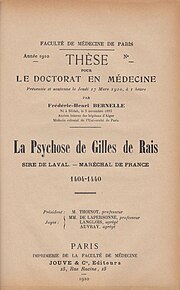

His thesis was developed "in a particular context, where debates on the religious question, the memory of the Dreyfus Affair, and the reassurance of the scientific spirit are pushing for a "rehabilitation" In line with the zeitgeist,” explains historian Pierre Savy.

For Bataille, understanding such criminal behaviour, and thus being able to affabulate it, remained impossible in medieval times without the later assistance of Marquis de Sade and Sigmund Freud, whose works "explore these abysses" and "force humanity to recognize their existence, to designate, to name these virtualities", adds Bercé.

Prouteau led a team consisting of lawyers, writers, former French ministers, parliament members, a biologist and a medical doctor[312][313][314] before Judge Henri Juramy, who found Gilles de Rais not guilty.

[q] These descriptions of bloody and orgasmic rituals have no equivalent in every inquisitorial interrogation studied by Chiffoleau, because in this case the trial documents record murders and sadistic pleasures that had never been put down on paper before Marquis de Sade's literary work in the 18th century.

Essayist Michel Meurger [fr] notes that "the judicial Gilles de Rais, a man without a face, elusive to historical psychology, acquires a body and a mind" for the first time in this work, the starting point for the interplay of filiations from one century to the next.

[346][347] In 1863, French archivist and historian Auguste Vallet de Viriville added new, imaginary details to Rais' description : "He was a handsome young man, graceful, petulant, with a lively, playful spirit, but weak and frivolous.

"[14][348] Afterwards, 19th-century medical science participated in "the reification of the ultra-romantic legend" of Rais as an alleged "superior degenerate" and out of the ordinary character, magnified by French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans in his novel Là-bas (1891) as a Faustian scholar, artist, flamboyant mystic and "great sadist".

"[351] The most famous study of the period remains the work of German-Austrian psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), whose chapter on sexual sadism disorder invokes Gilles de Rais.

In this way, Alexandre Lacassagne and his peers pled for the possibility of the human species' "physical and moral regeneration" through public health and eugenics, against the atavistic and deterministic theory of the "born criminal" formulated by Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso.

Although peppered with fanciful inventions, Lacroix's book was perceived at the time as a reliable historical source by various physicians such as Krafft-Ebing, German psychiatrist Albert Moll and French forensic doctor Léon-Henri Thoinot.

"Fiction therefore facilitated Gilles' passage from historical to medical discourse", points out Zrinka Stahuljak, adding that Lacroix's literary forgery conveniently provided these physicians with a "scientific explanation of [Rais'] conduct".

[360] Subsequently, the connection between the criminal category of serial killers and the case of Gilles de Rais was occasionally used to refute the thesis of the latter's innocence, thanks to the mention of supposedly comparable murderers like Fritz Haarmann.

"[365] He acknowledges that his approach has been contested, but he claims not to confuse medieval and contemporary mentalities,[336] admitting, moreover, that "the abysses of the human psyche remain unfathomable and ... Gilles de Rais has definitely taken his secret to the grave".

[381] Writer Alain Jost notes its "dramatic effect is assured and the Manichean symbolism is obvious"; Gilles and Joan shared youth and military fame, their given names "sound good together", "their destinies will be both parallel and radically opposed: both tried and executed", one embodying demonic vice and the other holy virtue.

[383] In Joris-Karl Huysmans' novel Là-bas, the protagonist Durtal, planning to write a book about Rais, paints the Middle Ages in the vivid colors of crime and Satanism, while drawing a parallel between medieval times and "the 19th century fond of spiritualism, occultism and black masses".

This troop had been previously commanded by Jeanne des Armoises, a Joan of Arc impersonator, but her relationship with Rais remains "poorly documented and difficult to interpret", according to medievalist Jacques Chiffoleau.

In keeping with the French 15th-century fashion , [ 148 ] this artist's impression depicts a beardless Gilles de Rais, wearing the men's bowl cut . Dressed in plate armor , he holds a bascinet under his arm. His tabard is emblazoned with the House of Retz 's coat of arms .

Gouache adorning a manuscript of Charles Perrault 's Mother Goose Tales , 1695.