Girolamo Savonarola

Declaring that Florence would be the New Jerusalem, the world centre of Christianity and "richer, more powerful, more glorious than ever",[9] he instituted an extreme moralistic campaign, enlisting the active help of Florentine youth.

[13] Most of his biographers reject or ignore the account of his younger brother and follower, Maurelio (later fra Mauro), that in his youth Girolamo had been spurned by a neighbour, Laudomia Strozzi, to whom he had proposed marriage.

He studied Scripture, logic, Aristotelian philosophy and Thomistic theology in the Dominican studium, practised preaching to his fellow friars, and engaged in disputations.

One explanation is that he had alienated certain of his superiors, particularly fra Vincenzo Bandelli, or Bandello, a professor at the studium and future master general of the Dominicans, who resented the young friar's opposition to modifying the Order's rules against the ownership of property.

It seems that this was due to the initiative of the humanist philosopher-prince, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who had heard Savonarola in a formal disputation in Reggio Emilia and been impressed with his learning and piety.

Pico was in trouble with the Church for some of his unorthodox philosophical ideas (the famous "900 theses") and was living under the protection of Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Medici de facto ruler of Florence.

[24] After some delay, apparently due to the interference of his former professor fra Vincenzo Bandelli, now Vicar General of the Order, Lorenzo succeeded in bringing Savonarola back to Florence, where he arrived in May or June of that year.

Without mentioning names, he made pointed allusions to tyrants who usurped the freedom of the people, and he excoriated their allies, the rich and powerful who neglected and exploited the poor.

Scoffers dismissed him as an over-excited zealot and "preacher of the desperate" and sneered at his growing band of followers as Piagnoni—"Weepers" or "Wailers", an epithet they adopted.

As the populace took to the streets to expel Piero the Unfortunate, Lorenzo de' Medici's son and successor, Savonarola led a delegation to the camp of the French king in mid-November 1494.

After a short, tense occupation of the city, and another intervention by fra Girolamo (as well as the promise of a huge subsidy), the French resumed their journey southward on 28 November 1494.

Savonarola now declared that by answering his call to penitence, the Florentines had begun to build a new Ark of Noah which had saved them from the waters of the divine flood.

With Savonarola's advice and support (as a non-citizen and cleric he was ineligible to hold office), a Savonarolan political "party", dubbed "the Frateschi", took shape and steered the friar's program through the councils.

A new constitution enfranchised the artisan class, opened minor civic offices to selection by lot, and granted every citizen in good standing the right to a vote in a new parliament, the Consiglio Maggiore, or Great Council.

At Savonarola's urging, the Frateschi government, after months of debate, passed a "Law of Appeal" to limit the longtime practice of using exile and capital punishment as factional weapons.

He now claimed that he had predicted the deaths of Lorenzo de' Medici and of Pope Innocent VIII in 1492 and the coming of the sword to Italy—the invasion of King Charles of France.

As he had foreseen, God had chosen Florence, "the navel of Italy", as his favourite and he repeated: if the city continued to do penance and began the work of renewal it would have riches, glory and power.

Mary warns that the way will be hard both for the city and for him, but she assures him that God will fulfil his promises: Florence will be "more glorious, more powerful and richer than ever, extending its wings farther than anyone can imagine".

At his repeated insistence, new laws were passed against "sodomy" (which included male and female same-sex relations), adultery, public drunkenness, and other moral transgressions, while his lieutenant Fra Silvestro Maruffi organised boys and young men to patrol the streets to curb immodest dress and behaviour.

[35] For a time, Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503) tolerated friar Girolamo's strictures against the Church, but he was moved to anger when Florence declined to join his new Holy League against the French invader, and blamed it on Savonarola's pernicious influence.

He summoned the friar to appear before him in Rome, and when Savonarola refused, pleading ill health and confessing that he was afraid of being attacked on the journey, Alexander banned him from further preaching.

He not only attacked secret enemies at home whom he rightly suspected of being in league with the papal Curia, he condemned the conventional, or "tepid", Christians who were slow to respond to his calls.

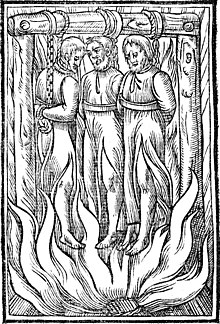

[47] On the morning of 23 May 1498, the three friars were led out into the main square where, before a tribunal of high clerics and government officials, they were condemned as heretics and schismatics, and sentenced to die forthwith.

They encouraged women in local convents and surrounding towns to find mystical inspiration in his example,[49] and, by preserving many of his sermons and writings, they helped keep his political as well as his religious ideas alive.

Savonarola's contemporary Niccolò Machiavelli discusses the friar in Chapter VI of his book The Prince, writing:[52]If Moses, Cyrus, Theseus, and Romulus had been unarmed they could not have enforced their constitutions for long—as happened in our time to Fra Girolamo Savonarola, who was ruined with his new order of things immediately the multitude believed in him no longer, and he had no means of keeping steadfast those who believed or of making the unbelievers to believe.Savonarolan religious ideas found a reception elsewhere.

[53] Within the Dominican Order Savonarola was seen as a devotional figure ("the evolving image of a Counter-Reformation saintly prelate"[54]), and in this benevolent guise his memory lived on.

This somewhat anachronistic image, fortified by much new scholarship, informed the major new biography by Pasquale Villari, who regarded Savonarola's preaching against Medici despotism as the model for the Italian struggle for liberty and national unification.

[56] In Germany, the Catholic theologian and church historian Joseph Schnitzer edited and published contemporary sources which illuminated Savonarola's career.

In 1924 he crowned his vast research with a comprehensive study of Savonarola's life and times in which he presented the friar as the last best hope of the Catholic Church before the catastrophe of the Protestant Reformation.

Today, most of Savonarola's treatises and sermons and many of the contemporary sources (chronicles, diaries, government documents, and literary works) are available in critical editions.