Glacier

Between latitudes 35°N and 35°S, glaciers occur only in the Himalayas, Andes, and a few high mountains in East Africa, Mexico, New Guinea and on Zard-Kuh in Iran.

[23] This contrast is thought to a large extent to govern the ability of a glacier to effectively erode its bed, as sliding ice promotes plucking at rock from the surface below.

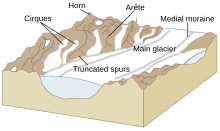

A glacier usually originates from a cirque landform (alternatively known as a corrie or as a cwm) – a typically armchair-shaped geological feature (such as a depression between mountains enclosed by arêtes) – which collects and compresses through gravity the snow that falls into it.

When the mass of snow and ice reaches sufficient thickness, it begins to move by a combination of surface slope, gravity, and pressure.

Glacial ice has a distinctive blue tint because it absorbs some red light due to an overtone of the infrared OH stretching mode of the water molecule.

Consequently, pre-glacial low hollows will be deepened and pre-existing topography will be amplified by glacial action, while nunataks, which protrude above ice sheets, barely erode at all – erosion has been estimated as 5 m per 1.2 million years.

If two rigid sections of a glacier move at different speeds or directions, shear forces cause them to break apart, opening a crevasse.

Glacial speed is affected by factors such as slope, ice thickness, snowfall, longitudinal confinement, basal temperature, meltwater production, and bed hardness.

[46] These surges may be caused by the failure of the underlying bedrock, the pooling of meltwater at the base of the glacier[47] — perhaps delivered from a supraglacial lake — or the simple accumulation of mass beyond a critical "tipping point".

[48] Temporary rates up to 90 m (300 ft) per day have occurred when increased temperature or overlying pressure caused bottom ice to melt and water to accumulate beneath a glacier.

During glacial periods of the Quaternary, Taiwan, Hawaii on Mauna Kea[58] and Tenerife also had large alpine glaciers, while the Faroe and Crozet Islands[59] were completely glaciated.

The permanent snow cover necessary for glacier formation is affected by factors such as the degree of slope on the land, amount of snowfall and the winds.

Glaciers can be found in all latitudes except from 20° to 27° north and south of the equator where the presence of the descending limb of the Hadley circulation lowers precipitation so much that with high insolation snow lines reach above 6,500 m (21,330 ft).

Areas of the Arctic, such as Banks Island, and the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica are considered polar deserts where glaciers cannot form because they receive little snowfall despite the bitter cold.

Even during glacial periods of the Quaternary, Manchuria, lowland Siberia,[60] and central and northern Alaska,[61] though extraordinarily cold, had such light snowfall that glaciers could not form.

[62][63] In addition to the dry, unglaciated polar regions, some mountains and volcanoes in Bolivia, Chile and Argentina are high (4,500 to 6,900 m or 14,800 to 22,600 ft) and cold, but the relative lack of precipitation prevents snow from accumulating into glaciers.

Abrasion leads to steeper valley walls and mountain slopes in alpine settings, which can cause avalanches and rock slides, which add even more material to the glacier.

Less apparent are ground moraines, also called glacial drift, which often blankets the surface underneath the glacier downslope from the equilibrium line.

Although the process that forms drumlins is not fully understood, their shape implies that they are products of the plastic deformation zone of ancient glaciers.

If multiple cirques encircle a single mountain, they create pointed pyramidal peaks; particularly steep examples are called horns.

[75] Researchers melt or crush samples from glacier ice cores whose progressively deep layers represent respectively earlier times in Earth's climate history.

[75] The researchers apply various instruments to the content of bubbles trapped in the cores' layers in order to track changes in the atmosphere's composition.

[75] Human activities in the industrial era have increased the concentration of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the air, causing current global warming.

[78] A study that investigated the period 1995 to 2022 showed that the flow velocity of glaciers in the Alps accelerates and slows down to a similar extent at the same time, despite large distances.

[79] Water runoff from melting glaciers causes global sea level to rise, a phenomenon the IPCC terms a "slow onset" event.

[80] Impacts at least partially attributable to sea level rise include for example encroachment on coastal settlements and infrastructure, existential threats to small islands and low-lying coasts, losses of coastal ecosystems and ecosystem services, groundwater salinization, and compounding damage from tropical cyclones, flooding, storm surges, and land subsidence.

This post-glacial rebound, which proceeds very slowly after the melting of the ice sheet or glacier, is currently occurring in measurable amounts in Scandinavia and the Great Lakes region of North America.

A radar instrument on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter found ice under a thin layer of rocks in formations called lobate debris aprons (LDAs).

[84][85][86] In 2015, as New Horizons flew by the Pluto-Charon system, the spacecraft discovered a massive basin covered in a layer of nitrogen ice on Pluto.

A large portion of the basin's surface is divided into irregular polygonal features separated by narrow troughs, interpreted as convection cells fueled by internal heat from Pluto's interior.