Passionate Journey

Passionate Journey, or My Book of Hours (French: Mon livre d'heures), is a wordless novel of 1919 by Flemish artist Frans Masereel.

At five his father died, and his mother remarried to a doctor in Ghent, whose political beliefs left an impression on the young Masereel.

[3] During World War I he volunteered as a translator for the Red Cross in Geneva, drew newspaper political cartoons, and copublished a magazine Les Tablettes, in which he published his first woodcut prints.

[7] From 1917 Masereel began publishing books of woodcut prints,[8] using similar imagery to make political statements on the strife of the common people rather than to illustrate the lives of Christ and the saints.

[1] Masereel self-published the book in Geneva on credit from Swiss printer Albert Kundig[9] in 1919 as Mon livre d'heures[10] in an edition of 200 copies.

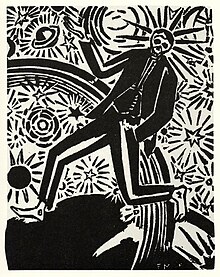

The 1926 edition had an introduction by German writer Thomas Mann:[11] Look at these powerful black-and-white figures, their features etched in light and shadow.

[12] He considered Passionate Journey partly autobiographical,[18] which he emphasized with a pair of self-portraits that open the book—in the first, Masereel sits at his desk with his woodcutting tools, and in the second appears the protagonist, dressed in identical fashion with the first.

[20] Wordless novel scholar David Beronä saw the work as a catalogue of human activity, and in this regard compared it to Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass and Allen Ginsberg's Howl.

[21] Austrian writer Stefan Zweig remarked, "If everything were to perish, all the books, monuments, photographs and memoirs, and only the woodcuts that [Masereel] has executed in ten years were spared, our whole present-day world could be reconstructed from them.

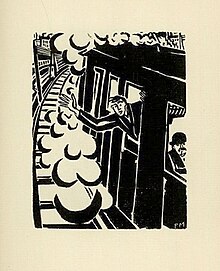

[2] In contrast to the works of Masereel's imitators, the images do not form an unfolding sequence of actions but are rather like individual snapshots of events in the protagonist's life.

[12] Wolf's edition of Passionate Journey went through multiple printings, and the book was popular throughout Europe, where it sold over 100,000 copies.

[13] Soon other publishers also engaged in the publication of wordless novels,[12] though none matched the success of Masereel's,[6] which Beronä has called "perhaps the most seminal work in the genre".

[24] While the graphic narrative bears strong similarities to the comics that were proliferating in the early 20th century, Masereel's book emerged from a fine arts environment and was aimed at such an audience.