Gold ground

Gold in mosaic began in Roman mosaics around the 1st century AD, and originally was used for details and had no particular religious connotation, but in Early Christian art it came to be regarded as very suitable for representing Christian religious figures, highlighting them against a plain but glistering background that might be read as representing heaven, or a less specific spiritual plane.

The style could not be used in fresco, but was adapted very successfully for miniatures in manuscripts and the increasingly important portable icons on wood.

[1] The style remains in use for Eastern Orthodox icons to the present day, but in Western Europe fell from popularity in the Late Middle Ages, as painters developed landscape backgrounds.

Writing in 1984, Otto Pächt said "the history of the colour gold in the Middle Ages forms an important chapter which has yet to be written",[2] a gap which perhaps has still only been partly filled.

The New Testament and patristic accounts of the Transfiguration of Christ were an especial focus of analysis, as Jesus is described as emitting or at least bathed in a special light, whose nature was discussed by theologians.

Unlike the main late medieval theory of optics in the West, where the viewer's eye was believed to emit rays that reached the viewed object, Byzantium believed the light proceeded from the object to the viewer's eye, and Byzantine art was very sensitive to alterations in the light conditions in which art was seen.

"[6] According to one scholar, "in a gold ground painting, the sacred image the Virgin, for example was firmly located on the material surface of the picture plane.

The other method was to use a water-soluble glue to fix the tesserae face down to a thin sheet; in modern times this is paper.

The leaf could then be "burnished", carefully rubbed with either the tooth of a dog or wolf, or a piece of agate, giving a brightly shining surface.

[15] According to Otto Pächt, it was only in the 12th century that Western illuminators learnt how to achieve the full burnished gold leaf effect from Byzantine sources.

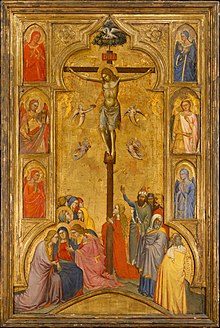

[17] In the West, the style was usual in Italo-Byzantine icon-style paintings from the 13th century onwards, inspired by the Byzantine icons reaching Europe after the Sack of Constantinople in 1204.

By the end of the century, increased numbers of Italian frescos were developing naturalistic backgrounds, as well as effects of mass and depth.

[18] This trend began to spread to panel paintings, although many still used the golden backgrounds until well into the 14th century, and indeed beyond, especially in more conservative centres such as Venice and Siena, and for major altarpieces.

[19] In Early Netherlandish painting the gold ground style was initially used, as in the Seilern Triptych of c. 1425 by Robert Campin, but a few years later his Mérode Altarpiece is given a famously detailed naturalistic setting.

The Roman painter Antoniazzo Romano and his workshop continued to use it into the first years of the 16th century, as he "made a speciality of repainting or interpreting older images, or generating new cult images with an archaic flavor",[22] Carlo Crivelli (died c. 1495), who for much of his career worked for relatively provincial patrons in the Marche region, also made late use of the style, to achieve sophisticated effects.

In 1762 George Stubbs painted three compositions with racehorses on a blank gold or honey background, much the largest being Whistlejacket (now National Gallery).

Viewing the pictures from this point you get a brilliant effect, like the brightness of day upon it; if from the other side you observe the light resolves itself into the rich, warm glow of the setting sun".

Apparently Klimt's interest in the style intensified after a visit to Ravenna in 1903, where his companion said that "the mosaics made an immense, decisive impression on him".

[29] The Cretan School continued using gold gilded backgrounds which became known as the Maniera Greca in the West, where many were exported, and is now called the Italo-Byzantine style.

Giorgio Vasari's famous book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects commented on the Greek technique unfavourably.

Clearly, the painter intentionally replaces the sky in his work with gold sheet while maintaining the modern flemish painting style escaping the Greek Italian Byzantine tradition.

[33] In Azuchi–Momoyama period Japan (1568–1600), the style became used in the large folding screens (byōbu) in the shiro or castles of the daimyo families by the late 16th century.

The amount of gold background varies between scenes, and is often mixed with architectural settings, blue skies, and other elements.

Later, mosaic became "the vehicle of choice for conveying the truth of Orthodox beliefs", as well as "the imperial medium par excellence".

[42] The traditional view, now challenged by some scholars, is that patterns of mosaic use spread from the court workshops of Constantinople, from which teams were sometimes despatched to other parts of the empire, or beyond as diplomatic gifts, and that their involvement can be deduced from the relatively higher quality of their production.

[47] In India it was mostly used in borders, or in elements of images, such as the sky; this is especially common in the showy style of Deccan painting.