Ottonian art

It emerged some decades into their rule and persisted past the Ottonian emperors into the reigns of the early Salian dynasty, which lacks an artistic "style label" of its own.

Like the former and unlike the latter, it was very largely a style restricted to a few of the small cities of the period, and important monasteries, as well as the court circles of the emperor and his leading vassals.

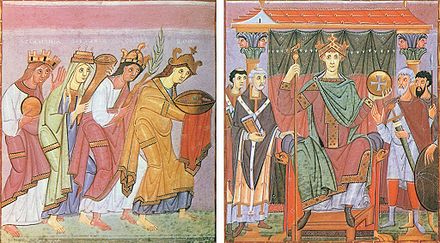

It was in this atmosphere that masterpieces were created that fused the traditions from which Ottonian artists derived their inspiration: models of Late Antique, Carolingian, and Byzantine origin.

Surviving Ottonian art is very largely religious, in the form of illuminated manuscripts and metalwork, and was produced in a small number of centres for a narrow range of patrons in the circle of the Imperial court, as well as important figures in the church.

[3] The style is generally grand and heavy, sometimes to excess, and initially less sophisticated than the Carolingian equivalents, with less direct influence from Byzantine art and less understanding of its classical models, but around 1000 a striking intensity and expressiveness emerge in many works, as "a solemn monumentality is combined with a vibrant inwardness, an unworldly, visionary quality with sharp attention to actuality, surface patterns of flowing lines and rich bright colours with passionate emotionalism".

For example, the many Ottonian ruler portraits typically include elements, such as province personifications, or representatives of the military and the Church flanking the emperor, with a lengthy imperial iconographical history.

[10] While secular jewellery supplied a steady stream of work for goldsmiths, ivory carving at this period was mainly for the church, and may have been centred in monasteries, although (see below) wall-paintings seems to have been usually done by laymen.

[11] The range of heavily illuminated texts was very largely restricted (unlike in the Carolingian Renaissance) to the main liturgical books, with very few secular works being so treated.

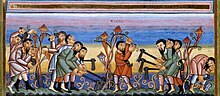

Some manuscripts also include relatively extensive cycles of narrative art, such as the sixteen pages of the Codex Aureus of Echternach devoted to "strips" in three tiers with scenes from the life of Christ and his parables.

[12] Heavily illuminated manuscripts were given rich treasure bindings and their pages were probably seen by very few; when they were carried in the grand processions of Ottonian churches it seems to have been with the book closed to display the cover.

[18] The outstanding miniaturist of the "Ruodprecht group" was the so-called Master of the Registrum Gregorii, or Gregory Master, whose work looked back in some respects to Late Antique manuscript painting, and whose miniatures are notable for "their delicate sensibility to tonal grades and harmonies, their fine sense of compositional rhythms, their feelings for the relationship of figures in space, and above all their special touch of reticence and poise".

[21] Backgrounds are often composed of bands of colour with a symbolic rather than naturalistic rationale, the size of figures reflects their importance, and in them "emphasis is not so much on movement as in gesture and glance", with narrative scenes "presented as a quasi-liturgical act, dialogues of divinity".

In Regensburg St. Emmeram's Abbey held the major Carolingian Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, which probably influenced a style with "an incisive line and highly formal organization of the page", giving in the Uta Codex of c. 1020 complex schemes where "bands of gold outline the bold, squares circles, ellipses, and rhombs that enclose the figures", and inscriptions are incorporated in the design explicating its complex theological symbolism.

[25] Other important monastic scriptoria that flourished during the Ottonian age include those at Salzburg,[26] Hildesheim, Corvey, Fulda, and Cologne, where the Hitda Codex was made.

Objects for decorating churches such as crosses, reliquaries, altar frontals and treasure bindings for books were all made of or covered by gold, embellished with gems, enamels, crystals, and cameos.

[30] The few surviving pieces of secular jewellery are in similar styles, including the crown worn by Otto III as a child, which he presented to the Golden Madonna of Essen after he outgrew it.

[33] Other major objects include a reliquary of St Andrew surmounted by a foot in Trier,[34] and gold altar frontals for the Palace Chapel, Aachen and Basel Cathedral (now in Paris).

The late Carolingian upper cover of the Lindau Gospels (Morgan Library, New York) and the Arnulf Ciborium in Munich were important forerunners of the style, from a few decades before and probably from the same workshop.

[38] Around 980, Archbishop Egbert of Trier seems to have established the major Ottonian workshop producing cloisonné enamel in Germany, which is thought to have fulfilled orders for other centres, and after his death in 993 possibly moved to Essen.

[47] Among various stylistic groups and putative workshops that can be detected, that responsible for pieces including the panel from the cover of the Codex Aureus of Echternach and two diptych wings now in Berlin (all illustrated below) produced particularly fine and distinctive work, perhaps in Trier, with "an astonishing perception of the human form ... [and] facility in handling the material".

[49] The style of the figures is described by Peter Lasko as "very heavy, stiff, and massive ... with extremely clear and flat treatment of drapery ... in simple but powerful compositions".

[51] There is a record of bishop Gebhard of Constance hiring lay artists for a now vanished cycle at his newly foundation (983) of Petershausen Abbey, and laymen may have dominated the art of wall-painting, though perhaps sometimes working to designs by monastic illuminators.

[52] The church of St George at Oberzell on Reichenau Island has the best-known surviving scheme, though much of the original work has been lost and the remaining paintings to the sides of the nave have suffered from time and restoration.

A number of exhibitions held in Germany in the years following World War II helped introduce the subject to a wider public and promote the understanding of art media other than manuscript illustrations.