Gold mining

[2] A group of German and Georgian archaeologists claims the Sakdrisi site in southern Georgia, dating to the 3rd or 4th millennium BC, may be the world's oldest known gold mine.

The ancient Sumerians, around 2500 BCE, developed sophisticated techniques for extracting gold from alluvial deposits and underground mines.

[6] During the Bronze Age, sites in the Eastern Desert became a great source of gold-mining for nomadic Nubians, who used "two-hand-mallets" and "grinding ore extraction."

[6][7] Additionally, gold was associated with the sun god Ra and was believed to be eternal and indestructible, symbolising the pharoah's divine power and afterlife.

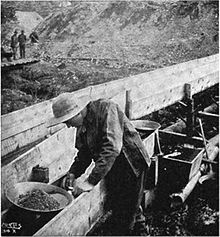

[10] Romans employed slave labour and used hydraulic mining methods, such as hushing and ground sluicing on a large scale to extract gold from extensive alluvial (loose sediment) deposits, such as those at Las Medulas.

Gold was a prime motivation for the campaign in Dacia when the Romans invaded Transylvania in what is now modern Romania in the second century AD.

[13] Under the Eastern Roman Empire Emperor Justinian's rule, gold was mined in the Balkans, Anatolia, Armenia, Egypt, and Nubia.

Golden objects found in Harappa and Mohenjo-daro have been traced to Kolar through the analysis of impurities – the impurities include 11% silver concentration, found only in KGF ore.[citation needed] The Champion reef at the Kolar gold fields was mined to a depth of 50 metres (160 ft) during the Gupta period in the fifth century AD.

The first recorded instances of placer mining are from ancient Rome, where gold and other precious metals were extracted from streams and mountainsides using sluices and panning[41] (ruina montium).

Smaller dredges with 50-to-100-millimetre (2 to 4 in) suction tubes are used to sample areas behind boulders and along potential pay streaks, until "colour" (gold) appears.

Other larger scale dredging operations take place on exposed river gravel bars at seasonal low water.

These operations typically use a land based excavator to feed a gravel screening plant and sluice box floating in a temporary pond.

[66][67] Miners risk government persecution, mine shaft collapses, and toxic poisoning from unsafe chemicals used in processing, such as mercury.

[62] Children in these mines suffer extremely harsh working conditions and various hazards such as collapsing tunnels, explosions, and chemical exposure.

[70] Local communities are frequently vulnerable to environmental degradation caused by large mining companies and may lack government protection or industry regulation.

[69] For example, thousands of people around Lega Dembi mine are exposed to mercury, arsenic, and other toxins resulting in widespread health problems and birth defects.

Gold mining activities in tropical forests are increasingly causing deforestation along rivers and in remote areas rich in biodiversity.

Rainforest recovery rates are the lowest ever recorded for tropical forests, with there being little to no tree regeneration at abandoned mining camps, even after several years.

[85][75][86] Mining activities can disturb soil structure, leading to erosion, sedimentation of waterways, and loss of fertile land for agriculture or vegetation regrowth.

[87][88] Large-scale gold mining projects may require land acquisition and resettlement of local communities, leading to displacement, loss of livelihoods, and disruption of traditional ways of life.

These chemicals pose risks to gold miners, communities, and wildlife; resulting in further medical problems involving neurological disorders and waterborne diseases.

[95][96] Artisanal gold mining is widespread across Africa, occurring in numerous countries including Ghana, Mali, Burkina Faso, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and many others.

[97] For many individuals and communities in rural Africa, artisanal gold mining represents a critical source of income and livelihood, providing employment opportunities and economic support in regions with limited alternative options.

The discovery of significant gold deposits in a region often sees a flood of resources and development, which lasts as long as the mines are economic.

When goldfields begin to decline in production, local economies find themselves destabilised and overly reliant upon an industry that will inevitably abandon the region when gold deposits are sufficiently depleted;[101][102] leaving the areas without proper rehabilitation.

[102] The some instances, the 'resource curse' phenomenon may occur, where countries rich in natural resources, like gold, may experience economic challenges, corruption, inequality, and governence issues instead of sustained development.

Fluctuation in gold prices can influence investment decisions, currency values, and trade balances in gold-producing and consuming countries.

Ensuring ethical and sustainable practices throughout this supply chain, including addressing issues such as child labour and environmental degradation, remains a challenge.

A UN investigation reported human rights abuses such as sexual exploitation of women and children, mercury poisoning, and child labor affecting communities where illegal gold production occurs.

[117] Gold demand is subdivided into central bank reserve increases, jewellery production, industrial consumption (including dental), and investment (bars, coins, exchange-traded funds, etc.)