Golf ball

It is commonly believed that hard wooden, round balls, made from hardwoods such as beech and box, were used for golf from the 14th through the 17th centuries.

Because gutties were cheaper to produce, could be re-formed if they became out-of-round or damaged, and had improved aerodynamic qualities, they soon became the preferred ball for use.

For decades, the wound rubber ball consisted of a liquid-filled or solid round core that was wound with a layer of rubber thread into a larger round inner core and then covered with a thin outer shell made of balatá sap.

The tree is tapped and the soft, viscous fluid released is a rubber-like material similar to gutta-percha, which was found to make an ideal cover for a golf ball.

[11] In the mid-1960s, a new synthetic resin, an ionomer of ethylene acid named Surlyn was introduced by DuPont as were new urethane blends for golf ball covers, and these new materials soon displaced balatá as they proved more durable and more resistant to cutting.

Titleist's Pro V1, Taylormade TP5, and Callaway Supersoft exemplify modern advancements in golf ball aerodynamics.

The Titleist Pro V1 boasts a tightly wound 388-dimple design, minimizing gaps between dimples for better aerodynamics.

However, due to the industrial revolution and the invention of vulcanization, balls increasingly became made from non-biodegradable materials.

During the late 2000's a few new biodegradable golf balls came into the market, including some made from wood, lobster shells or cornstarch.

[19] Additional rules direct players and manufacturers to other technical documents published by the R&A and USGA with additional restrictions, such as radius and depth of dimples, maximum launch speed from test apparatus (generally defining the coefficient of restitution) and maximum total distance when launched from the test equipment.

[22] Second, backspin generates lift by deforming the airflow around the ball,[23] in a similar manner to an airplane wing.

[24] Backspin is imparted in almost every shot due to the golf club's loft (i.e., angle between the clubface and a vertical plane).

[25] Curvature of the ball flight occurs when the clubface is not aligned perpendicularly to the club direction at impact, leading to an angled spin axis that causes the ball to curve to one side or the other based on difference between the face angle and swing path at impact.

Some dimple designs claim to reduce the sidespin effects to provide a straighter ball flight.

He then developed a pattern consisting of regularly spaced indentations over the entire surface, and later tools to help produce such balls in series.

The USGA refused to sanction it for tournament play and, in 1981, changed the rules to ban aerodynamic asymmetrical balls.

Today, golf balls are manufactured using a variety of different materials, offering a range of playing characteristics to suit the player's abilities and desired flight and landing behaviours.

Backspin creates lift that can increase carry distance, and also provides "bite" which allows a ball to arrest its forward motion at the initial point of impact, bouncing straight up or even backwards, allowing for precision placement of the ball on the green with an approach shot.

However, high-spin cover materials, typically being softer, are less durable which shortens the useful life of the ball, and backspin is not desirable on most long-distance shots, such as with the driver, as it causes the shot to "balloon" and then to bite on the fairway, when additional rolling distance is usually desired.

This allows designers to arrange the dimple patterns in such a way that the resistance to spinning is lower along certain axes of rotation and higher along others.

This causes the ball to "settle" into one of these low-resistance axes that (golfers hope) is close to parallel with the ground and perpendicular to the direction of travel, thereby eliminating "sidespin" induced by a slight mishit, which will cause the ball to curve off its intended flight path.

Their low compression and side spin reduction characteristics suit the lower swing speeds of average golfers quite well.

To accomplish these ends, practice balls are typically harder-cored than even recreational balls, have a firmer, more durable cover to withstand the normal abrasion caused by a club's hitting surface, and are made as cheaply as possible while maintaining a durable, quality product.

Balls hit into water hazards, penalty areas, buried deeply in sand, and otherwise lost or abandoned during play are a constant source of litter that groundskeepers must contend with, and can confuse players during a round who may hit an abandoned ball (incurring a penalty by strict rules).

Once collected, they may be discarded, kept by the groundskeeping staff for their own use, repurposed on the club's driving range, or sold in bulk to a recycling firm.

To avoid a loss of money on materials and labor, however, the balls which still generally conform to the Rules are marked to obscure the brand name (usually with a series of "X"s, hence the most common term "X-out"), packaged in generic boxes and sold at a deep discount.

Typically, the flaw that caused the ball to fail QC does not have a significant effect on its flight characteristics (balls with serious flaws are usually discarded outright at the manufacturing plant), and so these "X-outs" will often perform identically to their counterparts that have passed the company's QC.

Therefore, when playing in a tournament or other event that requires the ball used by the player to appear on this list as a "condition of competition", X-outs of any kind are illegal.

When the player hits a ball into a target, they receive distance and accuracy information calculated by the computer.

The previous record of 302 km/h (188 mph) was held by José Ramón Areitio, a Jai Alai player.

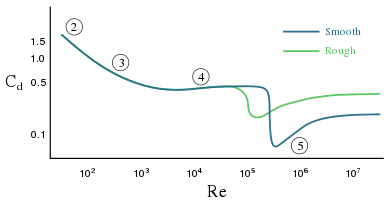

•2: attached flow ( Stokes flow ) and steady separated flow ,

•3: separated unsteady flow, having a laminar flow boundary layer upstream of the separation, and producing a vortex street ,

•4: separated unsteady flow with a laminar boundary layer at the upstream side, before flow separation, with downstream of the sphere a chaotic turbulent wake ,

•5: post-critical separated flow, with a turbulent boundary layer.