Government in Anglo-Saxon England

Kings had extensive powers to make laws, mint coins, levy taxes, raise armies, regulate trade, and conduct diplomacy.

[3] Britain's security deteriorated as the Roman army was gradually withdrawn and redeployed to other parts of the Empire to defend against barbarian invasions.

[5] After Roman rule, Britain experienced widespread anarchy, peasant revolt, and the rise of warlords, such as Vortigern and Ambrosius Aurelianus.

Around half the population were free, independent farmers (Old English: ceorls) who cultivated enough land to provide for a family (a unit called a hide).

These caused famine and other societal disruptions that may have increased violence and led previously independent farmers to submit to the rule of strong lords.

The surrounding population delivered food rent to a royal vill, which would be consumed by the king and his comitatus when they visited on their regular travels through the kingdom.

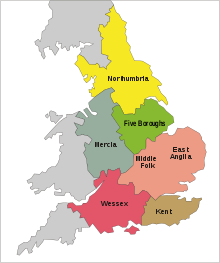

[19] Consolidation through war and marriage meant that by the 9th century only four kingdoms remained: East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, and Wessex.

[20] In his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Bede lists seven kings who achieved imperium or overlordship over England south of the Humber.

[21] The first four overlords were Ælle of Sussex (late 5th century), Ceawlin of Wessex (r. 560–592), Æthelberht of Kent (r. 589–616), and Rædwald of East Anglia (r. 599–624).

[24] Historian H. R. Loyn remarked that "some hazy imperial ideas" were associated with the bretwaldaship, such as influence over the English church, military leadership against the native Britons, and receiving tribute.

When the throne became vacant, a kingdom's witan (secular and ecclesiastical "wise men") chose the new king from among eligible candidates of the ruling dynasty.

In 787, Ecgfrith of Mercia became the first Anglo-Saxon king anointed with holy oil, imitating Carolingian and biblical precedents.

He presided in person as judge of the royal court, which could sentence freemen to death, enslavement, or impose financial penalties.

[39] In the 850s, England faced a formidable threat as Viking invaders, led by their Great Heathen Army, conquered most Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

The ealdormen were entrusted with crucial responsibilities, including the management of the army, fortifications, and tax collection in their respective shires.

[46] Kings had extensive powers to make laws, mint coins, levy taxes, raise armies, regulate trade, and conduct diplomacy.

[52] The laws of Cnut defined king's pleas as:[53][54] From 899 to 1016, a direct descendant of Alfred the Great of the House of Wessex sat on the English throne.

[62] Ælfthryth, Edgar's second wife, is believed to have assassinated Edward the Martyr (r. 975–978) to pave the way for her son, Æthelred the Unready (r. 978–1016), to become king.

[45] As part of the coronation ritual, kings swore a three-part oath:[63] Firstly, that the Church of God and all Christian people keep true peace, by my command.

In 1066, Harold Godwinson was crowned at the newly consecrated Westminster Abbey, which remained the customary place of coronation for future kings.

Within the chapel was a scriptorium or writing office dedicated to producing charters, writs, royal letters, and other official documents.

[80] Whenever the king asked a large or small group of nobles to advise him and to witness or consent to a royal action, that assembly was a witan.

In the words of Lyon, kings "seemed to feel that to consult with men from all parts of the kingdom produced a wider sampling of opinion and gave the law more solid support".

After Viking attacks resumed in the 980s, English kings used Danegeld to fund tribute payments until England's conquest by Danish prince Cnut the Great.

The heregeld was abolished in 1049 by Edward the Confessor, who placed responsibility for naval defense on the Cinque Ports in return for special privileges.

[96][99] Cnut's realm, the North Sea Empire, extended beyond England, and he was forced to delegate viceregal power to his earls.

[106] The sheriff (or sometimes the earl)[107] and the bishop presided, but there was no judge in the modern sense (royal justices would not sit in shire courts until the reign of Henry I).

The suitors of the court (bishops, earls, and thegns) declared the law and decided what proof of innocence or guilt to accept (such as ordeal or compurgation).

The king could grant ecclesiastical and lay lords the right of sac and soc ("cause and suit"), toll and team, and infangenetheof over their estates.

[118] In addition to the regular divisions of a shire, there also existed special jurisdictions called liberties where the sheriff had limited power and where dues owed to the king were granted to local lords.