Gravitational constant

In SI units, its value is approximately 6.6743×10−11 m3 kg−1 s−2.[1] The modern notation of Newton's law involving G was introduced in the 1890s by C. V. Boys.

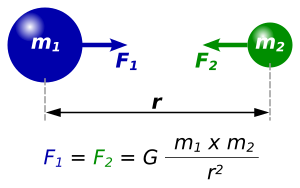

[b] According to Newton's law of universal gravitation, the magnitude of the attractive force (F) between two bodies each with a spherically symmetric density distribution is directly proportional to the product of their masses, m1 and m2, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance, r, directed along the line connecting their centres of mass:

The gravitational constant appears in the Einstein field equations of general relativity,[4][5]

[d] In SI units, the CODATA-recommended value of the gravitational constant is:[1] The relative standard uncertainty is 2.2×10−5.

In astrophysics, it is convenient to measure distances in parsecs (pc), velocities in kilometres per second (km/s) and masses in solar units M⊙.

For situations where tides are important, the relevant length scales are solar radii rather than parsecs.

It follows that This way of expressing G shows the relationship between the average density of a planet and the period of a satellite orbiting just above its surface.

The above equation is exact only within the approximation of the Earth's orbit around the Sun as a two-body problem in Newtonian mechanics, the measured quantities contain corrections from the perturbations from other bodies in the solar system and from general relativity.

For this purpose, the Gaussian gravitational constant was historically in widespread use, k = 0.01720209895 radians per day, expressing the mean angular velocity of the Sun–Earth system.

[citation needed] The use of this constant, and the implied definition of the astronomical unit discussed above, has been deprecated by the IAU since 2012.

[citation needed] The existence of the constant is implied in Newton's law of universal gravitation as published in the 1680s (although its notation as G dates to the 1890s),[12] but is not calculated in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica where it postulates the inverse-square law of gravitation.

[13] Nevertheless, he had the opportunity to estimate the order of magnitude of the constant when he surmised that "the mean density of the earth might be five or six times as great as the density of water", which is equivalent to a gravitational constant of the order:[14] A measurement was attempted in 1738 by Pierre Bouguer and Charles Marie de La Condamine in their "Peruvian expedition".

[15] The Schiehallion experiment, proposed in 1772 and completed in 1776, was the first successful measurement of the mean density of the Earth, and thus indirectly of the gravitational constant.

[16] This immediately led to estimates on the densities and masses of the Sun, Moon and planets, sent by Hutton to Jérôme Lalande for inclusion in his planetary tables.

The first direct measurement of gravitational attraction between two bodies in the laboratory was performed in 1798, seventy-one years after Newton's death, by Henry Cavendish.

[17] He determined a value for G implicitly, using a torsion balance invented by the geologist Rev.

It is surprisingly accurate, about 1% above the modern value (comparable to the claimed relative standard uncertainty of 0.6%).

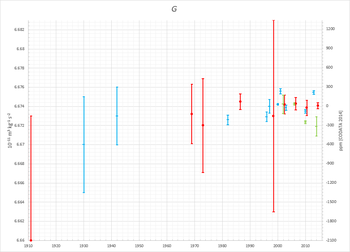

[18] The accuracy of the measured value of G has increased only modestly since the original Cavendish experiment.

[19] G is quite difficult to measure because gravity is much weaker than other fundamental forces, and an experimental apparatus cannot be separated from the gravitational influence of other bodies.

Measurements with pendulums were made by Francesco Carlini (1821, 4.39 g/cm3), Edward Sabine (1827, 4.77 g/cm3), Carlo Ignazio Giulio (1841, 4.95 g/cm3) and George Biddell Airy (1854, 6.6 g/cm3).

Pendulum experiments still continued to be performed, by Robert von Sterneck (1883, results between 5.0 and 6.3 g/cm3) and Thomas Corwin Mendenhall (1880, 5.77 g/cm3).

In addition to Poynting, measurements were made by C. V. Boys (1895)[25] and Carl Braun (1897),[26] with compatible results suggesting G = 6.66(1)×10−11 m3⋅kg−1⋅s−2.

The modern notation involving the constant G was introduced by Boys in 1894[12] and becomes standard by the end of the 1890s, with values usually cited in the cgs system.

Richarz and Krigar-Menzel (1898) attempted a repetition of the Cavendish experiment using 100,000 kg of lead for the attracting mass.

[27] Arthur Stanley Mackenzie in The Laws of Gravitation (1899) reviews the work done in the 19th century.

[28] Poynting is the author of the article "Gravitation" in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1911).

[30] However, Heyl used the statistical spread as his standard deviation, and he admitted himself that measurements using the same material yielded very similar results while measurements using different materials yielded vastly different results.

[32] For the 2014 update, CODATA reduced the uncertainty to 46 ppm, less than half the 2010 value, and one order of magnitude below the 1969 recommendation.

As of 2018, efforts to re-evaluate the conflicting results of measurements are underway, coordinated by NIST, notably a repetition of the experiments reported by Quinn et al.

[47] These are claimed as the most accurate measurements ever made, with standard uncertainties cited as low as 12 ppm.