Cavendish experiment

The experiment was devised sometime before 1783 by geologist John Michell,[6][7] who constructed a torsion balance apparatus for it.

After his death the apparatus passed to Francis John Hyde Wollaston and then to Cavendish, who rebuilt it, but kept close to Michell's original plan.

Cavendish then carried out a series of measurements with the equipment and reported his results in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1798.

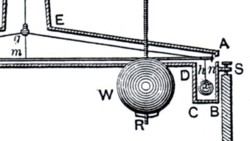

[8] The apparatus consisted of a torsion balance made of a six-foot (1.8 m) wooden rod horizontally suspended from a wire, with two 2-inch-diameter (51 mm), 1.61-pound (0.73 kg) lead spheres, one attached to each end.

[9] The experiment measured the faint gravitational attraction between the small and large balls, which deflected the torsion balance rod by about 0.16" (or only 0.03" with a stiffer suspending wire).

Their mutual attraction to the small balls caused the arm to rotate, twisting the suspension wire.

[14] To prevent air currents and temperature changes from interfering with the measurements, Cavendish placed the entire apparatus in a mahogany box about 1.98 meters wide, 1.27 meters tall, and 14 cm thick,[1] all in a closed shed on his estate.

Through two holes in the walls of the shed, Cavendish used telescopes to observe the movement of the torsion balance's horizontal rod.

The key observable was of course the deflection of the torsion balance rod, which Cavendish measured to be about 0.16" (or only 0.03" for the stiffer wire used mostly).

[15] Cavendish was able to measure this small deflection to an accuracy of better than 0.01 inches (0.25 mm) using vernier scales on the ends of the rod.

[17] Cavendish's result provided additional evidence for a planetary core made of metal, an idea first proposed by Charles Hutton based on his analysis of the 1774 Schiehallion experiment.

[19] The formulation of Newtonian gravity in terms of a gravitational constant did not become standard until long after Cavendish's time.

In Cavendish's time, physicists used the same units for mass and weight, in effect taking g as a standard acceleration.

The density of the Earth was hence a much sought-after quantity at the time, and there had been earlier attempts to measure it, such as the Schiehallion experiment in 1774.