Great Depression in Canada

Widespread losses of jobs and savings ultimately transformed the country by triggering the birth of social welfare, a variety of populist political movements, and a more activist role for government in the economy.

New rules limited immigration to British and American subjects or agriculturalists with money, certain classes of workers, and immediate family of the Canadian residents.

The fall of wheat prices drove many farmers to the towns and cities, such as Calgary, Alberta; Regina, Saskatchewan; and Brandon, Manitoba.

The labour unions largely retreated in response to the ravages of the depression at the same time that significant portions of the working class, including the unemployed, clamoured for collective action.

Some notable ones include a coal miners strike that resulted in the Estevan Riot in Estevan, Saskatchewan where four miners were killed by the RCMP in 1931, a waterfront strike in Vancouver that culminated with the "Battle of Ballantyne Pier" in 1935, and numerous unemployed demonstrations up to and including the On-to-Ottawa Trek that left one Regina police constable and one protester dead in the "Regina Riot".

Agitation and unrest nonetheless persisted throughout the depression, marked by periodic clashes, such as a sit-down strike in Vancouver that ended with "Bloody Sunday".

These developments had far-reaching consequences in shaping the postwar environment, including the domestic cold war climate, the rise of the welfare state, and the implementation of an institutional framework for industrial relations.

Women's primary role were as housewives; without a steady flow of family income, their work became much harder in dealing with food and clothing and medical care.

These strategies show that women's domestic labor—cooking, cleaning, budgeting, shopping, childcare—was essential to the economic maintenance of the family and offered room for economies.

[16] Srigley emphasizes the wide range of background factors and family circumstances, arguing that gender itself was typically less important than race, ethnicity, or class.

To save money the districts consolidated nearby schools, dropped staff lines, postponed new construction, and increased class size.

[23] The Stock Market crash in New York led people to hoard their money; as consumption fell, the American economy steadily contracted, 1929-32.

This hurt the Canadian economy more than most other countries in the world, and Canada retaliated by raising its own rates on American exports and by switching business to the Empire.

The onset of the depression created critical balance of payment deficits, and it was largely the extension of imperial protection by Britain that gave Canada the opportunity to increase their exports to the British market.

Thus, the British market played a vital role in helping Canada and Australia stabilize their balance of payments in the immensely difficult economic conditions of the 1930s.

Newfoundland (an independent dominion at the time) was bankrupt economically and politically and gave up responsible government by reverting to direct British control.

First World War veterans built on a history of postwar political activism to play an important role in the expansion of state-sponsored social welfare in Canada.

Arguing that their wartime sacrifices had not been properly rewarded, veterans claimed that they were entitled to state protection from poverty and unemployment on the home front.

The rhetoric of patriotism, courage, sacrifice, and duty created powerful demands for jobs, relief, and adequate pensions that should, veterans argued, be administered as a right of social citizenship and not a form of charity.

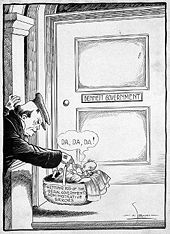

With falling support and the depression only getting worse, Bennett attempted to introduce policies based on the New Deal of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the United States.

The judicial and political failure of Bennett's New Deal legislation shifted the struggle to reconstitute capitalism to the provincial and municipal levels of the state.

Attempts to deal with the dislocations of the Great Depression in Ontario focused on the "sweatshop crisis" that came to dominate political and social discourse after 1934.

After 1936 the prime minister lost patience when westerners preferred radical alternatives such as the CCF (Co-operative Commonwealth Federation) and Social Credit to his middle-of-the-road liberalism.

"[28] Instead he paid more attention to the industrial regions and the needs of Ontario and Quebec regarding the proposed St. Lawrence Seaway project with the United States.

"Bible Bill" preached that the capitalist economy was rotten because of its immorality; specifically it produced goods and services but did not provide people with sufficient purchasing power to enjoy them.

Alberta's businessmen, professionals, newspaper editors and the traditional middle-class leaders vehemently protested Aberhart's crack-pot ideas, but they had not solved any problems and spoke not of the promised land ahead.

[34] The $25 monthly social dividend never arrived, as Aberhart decided nothing could be done until the province's financial system was changed, and 1936 Alberta defaulted on its bonds.

Although Aberhart was hostile to banks and newspapers, he was basically in favour of capitalism and did not support socialist policies as did the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in Saskatchewan.

[35] By 1938 the Social Credit government abandoned its notions about the $25 payouts, but its inability to break with UFA policies led to disillusionment and heavy defections from the party.

In the midst of the Great Depression, the Crown-in-Council attempted to uplift the people, and created two national corporations: the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (CRBC), and the Bank of Canada.