Great Depression in India

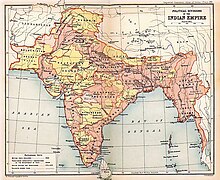

A global financial crisis, combined with protectionist policies adopted by the colonial government resulted in a rapid increase in the price of commodities in British India.

During the period 1929–1937, exports and imports in India fell drastically, crippling seaborne international trade in the region; the Indian railway and agricultural sectors were the most affected by the depression.

The Great Depression, along with the resulting economic policies from the colonial government, worsened already deteriorating Indo-British relations.

When the first general elections were held as stipulated in the Government of India Act 1935, anti-British feelings resulted in the pro-independence Indian National Congress winning in most provinces with a very high percentage of the vote share.

Since 1858, committees were established to investigate the possibility of cotton cultivation in India to provide raw materials for the mills in Lancashire.

[3] New technologies and industries were also introduced in India, albeit on a very small scale compared to developed nations of the world.

It remained low until 1925, when the then Chancellor of the Exchequer of United Kingdom, Winston Churchill, restored it to pre-War levels.

[6] India acted both as a supplier as well as a sprawling market for finished British goods in order to sustain Britain's wartime economy.

[6] However, the measures appeared symbolic and were intended to finance and protect British enterprise as was evident from the fact that all the benefactors were British-run industries.

[10] Moreover, imports were severely affected by the Swadeshi movement and the boycott of foreign goods imposed by Indian Freedom Fighters.

Most countries afflicted by the Great Depression such as Australia, New Zealand, Brazil and Denmark reduced the exchange value of their currencies.

[15] Therefore, having incurred heavy losses, farmers were compelled to sell off gold and silver ornaments in their possession in order to pay the land rent and other taxes.

[15] This gold intake was transported to the United Kingdom to compensate for the low bullion prices in the country and thereby revitalize the British economy, which was also experiencing a downturn due to the Great Depression|[4][15] The Viceroy of India, Lord Willingdon remarked that: For the first time in history, owing to the economic situation, Indians are disgorging gold.

As the national struggle intensified, the Government of India conceded some of the economic demands of the nationalists, including the establishment of a central bank.

[16] However, when Osborne Smith tried to function independently and indulged in open confrontation with P. J. Grigg, the finance member of the Viceroy's Council, he was removed from office.

[17] This was a remarkable shift of policy for the Indian National Congress as it had, till now, been a staunch advocate of dominion status.

The Government responded with a massive roundup, but by then, the march and the media coverage had radically moulded international opinion.