Great Pyramid of Giza

Over time, most of the smooth white limestone casing was removed, which lowered the pyramid's height to the current 138.5 metres (454.4 ft); what is seen today is the underlying core structure.

[18] The Great Pyramid's internal chambers lack inscriptions and decorations, the norm for Egyptian tombs of the fourth to late fifth dynasty, apart from work-gang graffiti that include Khufu's names.

For instance, Al-Maqrizi (1364–1442) reports the discovery of three shrouded bodies, a sarcophagus filled with gold, and a corpse in golden armour with a sword of inestimable value and a ruby as large as an egg.

Because of the differences in spelling, he did not recognize Khufu on Manetho's king list (as transcribed by Africanus and Eusebius),[61][full citation needed] hence he relied on Herodotus' incorrect account.

[44] The dating among Egyptologists still varied by multiple centuries (around 4000–2000 BC), depending on methodology, preconceived religious notions (such as the biblical deluge) and which source they thought was more credible.

It is still not a perfectly accurate method due to larger margins of error, calibration uncertainties and the problem of inbuilt age (time between growth and final usage) in plant material, including wood.

[70] Between 60 and 56 BC, the ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus visited Egypt and later dedicated the first book of his Bibliotheca historica to the land, its history, and its monuments, including the Great Pyramid.

[64] According to his report, neither Chemmis (Khufu) nor Cephren (Khafre) were buried in their pyramids, but rather in secret places, for fear that the people ostensibly forced to build the structures would seek out the bodies for revenge.

[73] Similar to Herodotus, Diodorus also claims that the side of the pyramid is inscribed with writing that "[set] forth [the price of] vegetables and purgatives for the workmen there were paid out over sixteen hundred talents.

The first textual evidence of this connection is found in the travel narratives of the female Christian pilgrim Egeria, who records that on her visit between 381 and 384 AD, "in the twelve-mile stretch between Memphis and Babylonia [= Old Cairo] are many pyramids, which Joseph made in order to store corn.

"[79] Ten years later the usage is confirmed in the anonymous travelogue of seven monks who set out from Jerusalem to visit the famous ascetics in Egypt, wherein they report that they "saw Joseph's granaries, where he stored grain in biblical times".

[80] This late 4th-century usage is further confirmed in the geographical treatise Cosmographia, written by Julius Honorius around 376 AD,[81] which explains that the Pyramids were called the "granaries of Joseph" (horrea Ioseph).

One legend in particular relates how, three hundred years prior to the Great Flood, Surid had a terrifying dream of the world's end, and so he ordered the construction of the pyramids so that they might house all the knowledge of Egypt and survive into the present.

[90] The author al-Kaisi, in his work the Tohfat Alalbab, retells the story of al-Ma'mun's entry but with the additional discovery of "an image of a man in green stone", which when opened revealed a body dressed in jewel-encrusted gold armour.

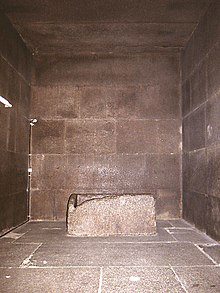

In addition to reasserting that Al-Ma'mun breached the structure in 820 AD, Al-Maqrizi's work also discusses the sarcophagus in the coffin chambers, explicitly noting that the pyramid was a grave.

[109] Worker graffiti found at Giza suggest haulers were divided into zau (singular za), groups of 40 men, consisting of four sub-units that each had an "Overseer of Ten".

[120] The sides of the Great Pyramid's base are closely aligned to the four geographic (not magnetic) cardinal directions, deviating on average 3 minutes and 38 seconds of arc, or about a tenth of a degree.

Precisely worked blocks were placed in horizontal layers and carefully fitted together with mortar, their outward faces cut at a slope and smoothed to a high degree.

[129][130] Unfinished casing blocks of the pyramids of Menkaure and Henutsen at Giza suggest that the front faces were smoothed only after the stones were laid, with chiselled seams marking correct positioning and where the superfluous rock would have to be trimmed off.

Amidst earthquakes in northern Egypt, workers (perhaps the descendants of those who served al-Ma'mun) stripped away many of the outer casing stones,[88] which were said to have been carted away by Bahri Sultan An-Nasir Nasir-ad-Din al-Hasan in 1356 for use in nearby Cairo.

[142][143] Laser scanning and photogrammetrical surveys concluded the concavities of the four sides to be the result of the removal of the casing stones, which damaged the underlying blocks that form the outer surface today.

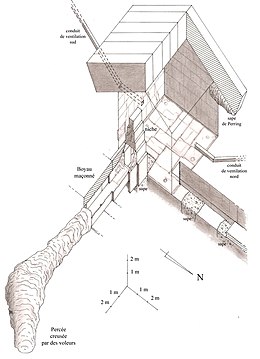

[99][151] According to Strabo (64–24 BC) a movable stone could be raised to enter this sloping corridor; however, it is not known if it was a later addition or original.A row of double chevrons diverts weight away from the entrance.

Most notable is a large, square text of hieroglyphs carved in honor of Frederick William IV, by Karl Richard Lepsius's Prussian expedition to Egypt in 1842.

[152] In 2016 the ScanPyramids team detected a cavity behind the entrance chevrons using muography, which was confirmed in 2019 to be a corridor at least 5 metres (16 ft) long, and running horizontal or sloping upwards (thus not parallel to the Descending Passage).

This theory is furthered by the report of patriarch Dionysius I Telmaharoyo, who claimed that before al-Ma'mun's expedition, there already existed a breach in the pyramid's north face that extended into the structure 33 metres (108 ft) before hitting a dead end.

Lazy guides used to block off this part with rubble to avoid having to lead people down and back up the long shaft, until around 1902 when Covington installed a padlocked iron grill-door to stop this practice.

Although seemingly known in antiquity, according to Herodotus and later authors, its existence had been forgotten in the Middle Ages until rediscovery in 1817, when Giovanni Caviglia cleared the rubble blocking the Descending Passage.

[168] In 1909, when the Edgar brothers' surveying activities were encumbered by the material, they moved the sand and smaller stones back into the shaft, leaving the upper part clear.

It is of the form common for early Egyptian sarcophagi, rectangular in shape with grooves to slide the now missing lid into place with three small holes for pegs to fix it.

[228][229] Herodotus visited Egypt in the 5th century BC and recounts a story that he was told concerning vaults under the pyramid built on an island where the body of Khufu lies.

- 1. Original entrance , North Face Corridor

- 2. Robbers' Tunnel (tourist entrance)

- 3, 4. Descending Passage

- 5. Subterranean Chamber

- 6. Ascending Passage

- 7. Queen's Chamber and its "air-shafts"

- 8. Horizontal Passage

- 9. Grand Gallery

- 10. King's Chamber and its "air-shafts"

- 11. Grotto and Well Shaft