Pullman Strike

[7] Historian David Ray Papke, building on the work of Almont Lindsey published in 1942, estimated that another 40 were killed in other states.

[9] The federal government obtained an injunction against the union, Debs, and other boycott leaders, ordering them to stop interfering with trains that carried mail cars.

Defended by a team including Clarence Darrow, Debs was convicted of violating a court order and sentenced to prison; the ARU then dissolved.

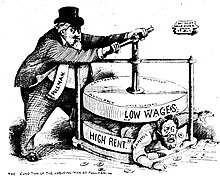

However, he did not cut rents nor lower prices at his company stores, nor did he give any indication of a commensurate cost of living adjustment.

The pressure put on by the population at the time on Pullman increased as ARU members used "unity" to shut down rail networks.

But, by refusing to engage in negotiations and receiving federal court orders to put an end to the strike, the railroads, who were unified under the General Managers' Association, showed all of its corporate power.

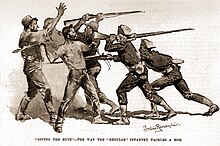

Conflict broke out between strikers and replacement workers that often turned violent in Chicago alone, and federal troops were eventually called in to bring the peace back.

The boycott revealed the amount of racial and economic divides while showing the growing influence of industrial labor unions.

Debs's arrest afterward stamped the Pullman Strike as a turning point in labor history by showing the federal government's preference for corporate interests over workers' rights.

[16] [17] [18] On June 29, 1894, Debs hosted a peaceful meeting to rally support for the strike from railroad workers at Blue Island, Illinois.

[13] Elsewhere in the western states, sympathy strikers prevented transportation of goods by walking off the job, obstructing railroad tracks, or threatening and attacking strikebreakers.

[citation needed] The strike was handled by US Attorney General Richard Olney, who was appointed by President Grover Cleveland.

A majority of the president's cabinet in Washington, D.C., backed Olney's proposal for federal troops to be dispatched to Chicago to put an end to the "rule of terror."

Olney got an injunction from circuit court justices Peter S. Grosscup and William Allen Woods (both anti-union) prohibiting ARU officials from "compelling or encouraging" any impacted railroad employees "to refuse or fail to perform any of their duties".

He called on ARU members to ignore the federal court injunctions and the U.S. Army:[20] Strong men and broad minds only can resist the plutocracy and arrogant monopoly.

[22] United States Marshall John W. Arnold told those in Washington that “no force less than regular troops could procure the passage of mail trains or enforce the orders of federal court”.

[citation needed] In Billings, Montana, an important rail center, a local Methodist minister, J. W. Jennings, supported the ARU.

In a sermon, he compared the Pullman boycott to the Boston Tea Party, and attacked Montana state officials and President Cleveland for abandoning "the faith of the Jacksonian fathers.

"[25] Rather than defending "the rights of the people against aggression and oppressive corporations," he said party leaders were "the pliant tools of the codfish monied aristocracy who seek to dominate this country.

"[25] Billings remained quiet but, on July 10, soldiers reached Lockwood, Montana, a small rail center, where the troop train was surrounded by hundreds of angry strikers.

[25] In California, the boycott was effective in Sacramento, a labor stronghold, but weak in the Bay Area and minimal in Los Angeles.

The strike lingered as strikers expressed longstanding grievances over wage reductions, and indicated how unpopular the Southern Pacific Railroad was.

Strikers engaged in violence and sabotage; the companies saw it as civil war, while the ARU proclaimed it was a crusade for the rights of unskilled workers.

[26] President Cleveland did not think Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld could manage the strike as it continued to cause more and more physical and economic damage.

News reports and editorials commonly depicted the strikers as foreigners who contested the patriotism expressed by the militias and troops involved, as numerous recent immigrants worked in the factories and on the railroads.

Conversely, Reverend William H. Cawardine, pastor of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Pullman, was a well-known supporter of the ARU and the striking workers.

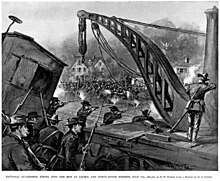

[34] Early in 1895, General Graham erected a memorial obelisk in the San Francisco National Cemetery at the Presidio in honor of four soldiers of the 5th Artillery killed in a Sacramento train crash of July 11, 1894, during the strike.

With this change the company would shift its focus away from its environmental strategy of having superior living and recreational accommodations to keep workers loyal, and would instead use the town of Pullman for more industrial purposes, building storage and repair shops in place of fields.

[42] Cleveland's administration appointed a national commission to study the causes of the 1894 strike; it found George Pullman's paternalism partly to blame and described the operations of his company town to be "un-American".

Samuel Gompers, who had sided with the federal government in its effort to end the strike by the American Railway Union, spoke out in favor of the holiday.