Ancient Greek astronomy

During the Hellenistic era and onwards, Greek astronomy expanded beyond the geographic region of Greece as the Greek language had become the language of scholarship throughout the Hellenistic world, in large part delimited by the boundaries of the Macedonian Empire established by Alexander the Great.

The most prominent and influential practitioner of Greek astronomy was Ptolemy, whose treatise Almagest shaped astronomical thinking until the modern era.

They include (a flat) earth, a heaven (firmament) where the sun, moon, and stars are located, an outer ocean surrounding the inhabited human realm, and the netherworld (Tartarus), the first three of which corresponded to the gods Ouranos, Gaia, and Oceanus (or Pontos).

[7] Like his predecessors, such as Hesiod and Homer, Thales accepted that the Earth was flat and rests on a primordial and endless ocean.

[9] Anaximander, a student of Thales and another prominent member of the Ionian school, realized that the northern sky seems to turn around the North star, which led him to the concept of a Celestial sphere around Earth.

The notion of a spherical Earth first found an audience with the Pythagoreans, but this was due to philosophical as opposed to scientific reasons: the sphere was considered a perfectly geometrical figure.

Five planets can be seen with the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, the Greek names being Hermes, Aphrodite, Ares, Zeus and Cronus.

The earliest extant description of the constellations, the Phaenomena of Aratus (270 BC), is the primary source for his work on this subject.

[19] Finally, in the 3rd century BCE, Aristarchus of Samos (sometimes called the "Ancient Copernicus"[20]) was the first and only premodern figure to propose a truly heliocentric model of the Solar System, placing the sun, not the earth, at the center of the universe.

[21] Plato and Eudoxus of Cnidus were both active in astronomical thought in the first half of the fourth century BC, and with them came a decisive shift in Greek astronomy.

A new two-sphere model of the solar system was proposed, and, for the first time, explanations for planetary observations were posited in the form of geometric theories.

Eudoxus established a school of thought that prioritized the use of geometrical models to explain the apparent paths of the stars.

[34] Claudius Ptolemy was a mathematician who worked in the city of Alexandria in Roman Egypt in the 2nd century AD, deeply examining the shape and motion of the Earth and other celestial bodies.

The Almagest was a monumental series of 13 books including roughly a quarter-million words in Greek that gave a comprehensive treatment of astrology until its time, incorporating theorems, models, and observations from many previous mathematicians.

Since the moon and other objects appear to change in size depending on the time of observation, it was understood that the earths distance to other astral bodies was changing, and that a simple circular motion of another body around the earth, as in the homocentric theory of Eudoxus, was unable to account for this.

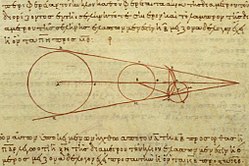

[38] Eccentrics and epicycles are the two main tools of Ptolemaic astronomy, and Ptolemy demonstrated that the two were closely related.

The models for Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars included the center of the circle, the equant point, the epicycle, and an observer from earth to give perspective.

Ptolemy's model of the cosmos and his studies landed him an important place in history in the development of modern-day science.

The circle of fixed stars marked the outermost sphere of the universe and beyond that would be the philosophical "aether" realm.

The sphere carrying the Moon is described as the boundary between the corruptible and changing sublunary world and the incorruptible and unchanging heavens above it.

Though Proclus criticized some elements of the Almagest, such as its suggestion of the existence of epicycles, he and future Neoplatonists believed astronomy was essential to theology and continued to read Ptolemy's works.

Students and successors of Proclus to continue working in the tradition of the Almagest included Hilarius of Antioch and Marinus.

The author of the original commentary is, however, not known, as many plausible candidates studied in the astronomy of Ptolemy lived in this era, such as Eutocius of Ascalon and John Philoponus.

[45] In addition to the authors named in the article, the following list of people who worked on mathematical astronomy or cosmology may be of interest.