Greek divination

As it is a form of compelling divinity to reveal its will by the application of method, it is, and has been since classical times, considered a type of magic.

[1] It depends on a presumed "sympathy" (Greek sumpatheia) between the mantic event and the real circumstance, which he denies as contrary to the laws of nature.

[4] A mantis is to be distinguished from a hiereus, "priest," or hiereia, "priestess," by the participation of the latter in the traditional religion of the city-state.

His mantosune, or "art of divination" (Cicero's mantike, which he translates into Latin as divinatio), endowed him with knowledge of past, present, and future, which he got from Apollo (Iliad A 68–72).

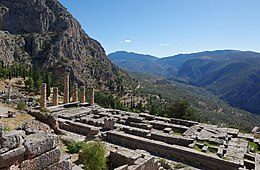

Although these oracles were located in sovereign city-states, they were granted a political "hands-off" status and free access so that delegations from anywhere could visit them.

The important generals and statesmen had their own prophets, to avoid such difficulties as Agamemnon experienced, when Calchas forced him to sacrifice his daughter and ransom his female prize in the opening of the Iliad.

Privately hired manteis, such as Alexander used, never seemed to disagree with command decisions, or if a possibly negative prophecy was received, made sure that it was given the most favorable interpretation.

By that time, based on what Cicero said, the leaders were probably skeptical of prophecy, but the beliefs of the superstitious soldiers were a factor to be considered.

[8] Oracles were known institutional centers committed to vatic practice, as opposed to individual practitioners for hire.

Part of the oracular administration was thus a team of what today would be called political scientists, as well as other scholars, who could perform such feats as rendering an oracle into the language of the applicant.

The cost was covered unknowingly by states and persons eager to make generous contributions to the god.

It has been necessary to supplement some of Smith's scanty descriptions with information from his sources, especially Plutarch Lives, Moralia and De Defectu Oraculorum.

The literary fragments suggest that Aristotle's view was generally believed, that the first Hellenes were of the tribe of the Selloi, or Helloi, in Epirus and that they called the country Hellopia.

If these fragments are to be believed, Epirus must have been an early settlement location of Indo-Europeans who were to become Greek speakers by evolution of the culture, especially language.

[18] Apollo, the most important oracular deity, is most closely associated with the supreme knowledge of future events which is the possession of Zeus.

His divination required the sacrifice of the commander's daughter to obtain the winds to bring the Greek fleet to Troy.

Of all oracles of ancient Hellenic culture and society, a man named Tiresias was thought as the most vital and important.

The divinator uses reason and conjecture to set up an experiment, so to speak, testing the god's will, such as determining to look at certain quarters of the sky at certain times for the presence of certain kinds of birds.

Events that happen according to natural law are given surcharges of prejudicial meaning, when the outcomes are really attributable to chance.

Gardner in the Oxford Companion to Greek Studies refers to “direct” or “spontaneous” and “indirect” or “artificial” divination, which turn out to be Quintus Cicero's “of nature” and “of art” respectively.

Attested techniques include, sleeping in conditions whereby dreams might be more likely to occur, inhaling mephitic vapour, chewing bay leaf, and drinking of blood.

Under the influence of this scientific view, recounted by Marcus Cicero, that the phenomenal world is driven by natural law, whether or not there is any divinity, the pre-Christian emperors suppressed artificial, or indirect, divination, attacking its social centers, the oracles, as political rivals.

Under this guise Quintus’ classification appeared again as “evoked” for “of art” and “spontaneous” for “of nature.”[33] The contest between the scientific view, which rejects all divination as superstition, and the religious view, which promulgates signs, continues in the present times, along with generally discredited remnants of indirect divination, such as reading the tea leaves, or Chinese fortune cookies.

Astragalomancy is a type of cleromancy performed by throwing the knuckle-bones of sheep or other ruminants (astragaloi[46]) to be able to tell the future.

[47] Hydromancy, or divination by water, is a Hellenic practice which still survives in the modern era (circa 2013).

[49] Herodotus provided a record of the prophetic productions resulting from Delphi as well as several instances of augury.

[49] Xenophon recorded his own meeting with a diviner named Eucleides,[6] in chapter 7 of his work Anabasis.

[49] Xenophon was thought to be skilled at foretelling from sacrifices, and attributed much of his knowledge to Socrates in "The Cavalry Commander".