Greek government-debt crisis

The crisis started in late 2009, triggered by the turmoil of the world-wide Great Recession, structural weaknesses in the Greek economy, and lack of monetary policy flexibility as a member of the eurozone.

[citation needed] The crisis led to a loss of confidence in the Greek economy, indicated by a widening of bond yield spreads and rising cost of risk insurance on credit default swaps compared to the other Eurozone countries, particularly Germany.

[35] "However, the sudden stop has not prompted the European periphery countries to move toward devaluation by abandoning the euro, in part because capital transfers from euro-area partners have allowed them to finance current account deficits".

[39] The Greek crisis was triggered primarily by the Great Recession, which led the budget deficits of several Western nations to reach or exceed 10% of GDP.

[10][11] Finally, dramatic revisions in Greek budget statistics were heavily reported on by media and condemned by other EU states,[41] leading to strong reactions in private bond markets.

[50] In the five years from 2005 to 2009, Eurostat noted reservations about Greek fiscal data in five semiannual assessments of the quality of EU member states' public finance statistics.

Yet, these deficit and debt statistics reported by Greece were again published with reservation by Eurostat, "due to uncertainties on the surplus of social security funds for 2009, on the classification of some public entities and on the recording of off-market swaps.

[90][91] By 28 July 2017, numerous businesses were required by law to install a point of sale (POS) device to enable them to accept payment by credit or debit card.

[119] A German derivatives dealer commented, "The Maastricht rules can be circumvented quite legally through swaps", and "In previous years, Italy used a similar trick to mask its true debt with the help of a different US bank.

[121] The Finance Ministry accepted the need to restore trust among investors and correct methodological flaws, "by making the National Statistics Service an independent legal entity and phasing in, during the first quarter of 2010, all the necessary checks and balances".

Specifically, questions have been raised about the way the cost of aforementioned previous actions such as cross currency swaps was estimated, and why it was retroactively added to the 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2009 budget deficits, rather than to those of earlier years, more relevant to the transactions.

[134] The government agreed to creditor proposals that Greece raise up to €50 billion through the sale or development of state-owned assets,[135] but receipts were much lower than expected, while the policy was strongly opposed by the left-wing political party, Syriza.

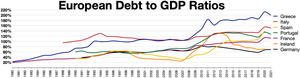

[151] This promise was that if Greece completed the program, but its debt-to-GDP ratio subsequently was forecast to be over 124% in 2020 or 110% in 2022 for any reason, then the Eurozone would provide debt-relief sufficient to ensure that these two targets would still be met.

[186][187] The third and last Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece was signed on 12 July 2015 by the Greek Government under prime minister Alexis Tsipras and it expired on 20 August 2018.

However, this shifted as the "troika" (ECB, IMF and a European government-sponsored fund) gradually replaced private investors as Greece's main creditor, by setting up the EFSF.

[210] In a May 2011 poll, 62% of respondents felt that the IMF memorandum that Greece signed in 2010 was a bad decision that hurt the country, while 80% had no faith in the Minister of Finance, Giorgos Papakonstantinou, to handle the crisis.

The International Monetary Fund therefore argued in 2015 that Greece's debt crisis could be almost completely resolved if the country's government found a way to solve the tax evasion problem.

[233][failed verification] Data for 2012 placed the Greek underground or "black" economy at 24.3% of GDP, compared with 28.6% for Estonia, 26.5% for Latvia, 21.6% for Italy, 17.1% for Belgium, 14.7% for Sweden, 13.7% for Finland, and 13.5% for Germany.

Consequently, because of financial shock, unemployment directly affects debt management, isolation, and unhealthy coping mechanisms such as depression, suicide, and addiction.

[250] However, the consequences of "Grexit" could be global and severe, including:[37][251][252][253] Greece could accept additional bailout funds and debt relief (i.e. bondholder haircuts or principal reductions) in exchange for greater austerity.

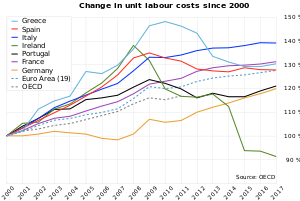

This reflected the difficulties that Spain, Portugal, Italy and Ireland had faced (along with Greece) before ECB-head Mario Draghi signaled a pivot to looser monetary policy.

"[281] OECD projections of relative export prices—a measure of competitiveness—showed Germany beating all Eurozone members except for crisis-hit Spain and Ireland for 2012, with the lead only widening in subsequent years.

[282] A study by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2010 noted that "Germany, now poised to derive the greatest gains from the euro's crisis-triggered decline, should boost its domestic demand" to help the periphery recover.

But if Germany is going to have only 1 percent inflation, we're talking about massive deflation in the periphery, which is both hard (probably impossible) as a macroeconomic proposition, and would greatly magnify the debt burden.

[295] The version of adjustment offered by Germany and its allies is that austerity will lead to an internal devaluation, i.e. deflation, which would enable Greece gradually to regain competitiveness.

[281] Almost four million German tourists—more than any other EU country—visit Greece annually, but they comprised most of the 50,000 cancelled bookings in the ten days after 6 May 2012 Greek elections, a figure The Observer called "extraordinary".

[305] Such is the ill-feeling, historic claims on Germany from WWII have been reopened,[306] including "a huge, never-repaid loan the nation was forced to make under Nazi occupation from 1941 to 1945.

"[307] Perhaps to curb some of the popular reactions, Germany and the eurozone members approve the 2019 budget of Greece, which called for no further pension cuts, in spite of the fact that these were agreed under the third memorandum.

[309][192] This had a critical effect: the debt-to-GDP ratio, the key factor defining the severity of the crisis, would jump from its 2009 level of 127%[193] to about 170%, solely due to the GDP drop (for the same debt).

[79] Similarly, negative reports about the Greek economy rarely mentioned the previous decades of Greece's high economic growth rates combined with low government debt.