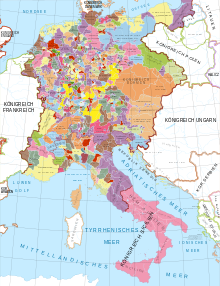

Guelphs and Ghibellines

The struggle for power between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire arose with the Investiture Controversy, which began in 1075 and ended with the Concordat of Worms in 1122.

Timeline The conflict between Guelphs and Ghibellines arose from the political divisions caused by the Investiture Controversy, about whether secular rulers or the pope had the authority to appoint bishops and abbots.

[10] The conflict between the two factions dominated the politics of medieval Italy, and persisted long after the confrontation between emperor and pope had ceased.

The conflicts between Guelphs and Ghibellines ended in the 14th century with the creation of a new situation, where the State and the laity began to withdraw from any ecclesiastical interference.

Frederick soon recovered and rebuilt an army, but this defeat encouraged resistance in many cities that could no longer bear the fiscal burden of his regime: parts of the Romagna, Marche and Spoleto were lost.

Basing himself in Piedmont in June, Frederick hosted many nobles of northern Italy and ambassadors from foreign kings in his court, and his deposition, it seems, had not diminished his fame or preeminence.

In the first month of the year, the indomitable Ranieri of Viterbo died, depriving pro-papal leadership in Italy of an implacable foe of Frederick.

Conrad, King of the Romans, scored several victories in Germany against William of Holland and forced the pro-papal Rhenish archbishops to sign a truce.

Innocent IV was increasingly isolated as support for the papal cause dwindled rapidly in Germany, Italy, and across Europe generally.

Even with imperial prospects brightening however, areas of Italy had been ravaged by years of war and even the resources of the wealthy and prosperous Kingdom of Sicily were strained.

Frederick's unified regime in Italy and Sicily was despotic and brutal, imposing harsh taxes and ruthlessly suppressing dissent.

Despite the betrayals, setbacks, and flux of fortune he had faced in his last years, Frederick died peacefully, reportedly wearing the habit of a Cistercian monk.

Of his father's death, Manfred wrote to Conrad in Germany, "The sun of justice has set, the maker of peace has passed away.

Everywhere Innocent IV's fortunes seemed dire: the papal treasury was depleted, his anti-king William of Holland had been defeated by Conrad in Germany and forced to submit while no other European monarch proved willing to offer much support for fear of Frederick's ire.

Despite the economic strains placed on the Regno, support from the Emperor of Nicaea, John III Doukas Vatatzes, enabled Frederick to relatively refill his coffers and resupply his forces.

After the failure of Louis IX's crusade in Egypt, Frederick had skillfully imaged himself as the aggrieved party against the papacy, hindered by Innocent's machinations from supporting the campaign.

Manfred received the principality of Taranto, 100,000 gold ounces, and regency over Sicily and Italy while his half-brother remained in Germany.

Perhaps aiming to lay stones for a potential peace settlement between Conrad and Innocent—or a final crafty scheme to further demonstrate papal prejudice against him, Frederick's will stipulated that all the lands he had taken from the Church were to be returned to it, all the prisoners freed, and the taxes reduced, provided this did not damage the Empire's prestige.

At his death, the Hohenstaufen empire remained the leading power in Europe and its security seemed assured in the persons of his sons.

That city remained with the Ghibelline factions, partly as a means of preserving its independence, rather than out of loyalty to the temporal power, as Forlì was nominally in the Papal States.

To identify themselves, people adopted distinctive customs such as wearing a feather on a particular side of their hats, or cutting fruit a particular way, according to their affiliation.

The conflict between Guelphs and Ghibellines was important in the Republic of Genoa, where the former were called rampini ("grappling hooks") and the latter mascherati ("masked"), although the origin of these terms is not clear.

They were forced to cease their resistance after several military campaigns: they were again accepted in the city's political life, after paying war expenses.

The term Ghibelline continued to indicate allegiance to the declining Imperial authority in Italy, and saw a brief resurgence during the Italian campaigns of Emperors Henry VII (1310) and Louis IV (1327).

[20] Since the Pope granted Sicily (Southern Italy) to the French prince Charles I of Anjou, the Guelphs took a pro-French stance.

The Guelph government became increasingly autocratic, leading to a Ghibelline conspiracy led by Giorgio Lampugnino and Teodoro Bossi.

The Mayor of Florence established the headquarters of the reborn Guelph Party in the historic Palazzo di Parte Guelfa in the city.

[25] Some individuals and families indicated their faction affiliation in their coats of arms by including an appropriate heraldic "chief" (a horizontal band at the top of the shield).

[27] During the 12th and 13th centuries, armies of the Ghibelline communes usually adopted the war banner of the Holy Roman Empire – white cross on a red field – as their own.

These two schemes are prevalent in the civic heraldry of northern Italian towns and remain a revealing indicator of their past factional leanings.