Printing press

It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the cloth, paper, or other medium was brushed or rubbed repeatedly to achieve the transfer of ink and accelerated the process.

[4] Gutenberg's newly devised hand mould made possible the precise and rapid creation of metal movable type in large quantities.

[8] The spread of mechanical movable type printing in Europe in the Renaissance introduced the era of mass communication, which permanently altered the structure of society.

The relatively unrestricted circulation of information and (revolutionary) ideas transcended borders, captured the masses in the Reformation, and threatened the power of political and religious authorities.

The sharp increase in literacy broke the monopoly of the literate elite on education and learning and bolstered the emerging middle class.

Across Europe, the increasing cultural self-awareness of its peoples led to the rise of proto-nationalism and accelerated the development of European vernaculars, to the detriment of Latin's status as lingua franca.

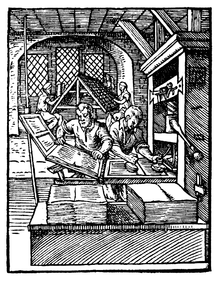

[10] The rapid economic and socio-cultural development of late medieval society in Europe created favorable intellectual and technological conditions for Gutenberg's improved version of the printing press: the entrepreneurial spirit of emerging capitalism increasingly made its impact on medieval modes of production, fostering economic thinking and improving the efficiency of traditional work processes.

The sharp rise of medieval learning and literacy amongst the middle class led to an increased demand for books which the time-consuming hand-copying method fell far short of accommodating.

[12] At the same time, a number of medieval products and technological processes had reached a level of maturity which allowed their potential use for printing purposes.

[13] Introduced in the 1st century AD by the Romans, it was commonly employed in agricultural production for pressing grapes for wine and olives for oil, both of which formed an integral part of the Mediterranean and medieval diet.

In Egypt during the Fatimid era, the printing technique was adopted reproducing texts on paper strips by hand and supplying them in various copies to meet the demand.

Gutenberg adapted the construction so that the pressing power exerted by the platen on the paper was now applied both evenly and with the required sudden elasticity.

Other notable examples include the Prüfening inscription from Germany, letter tiles from England and Altarpiece of Pellegrino II in Italy.

[25] The Latin alphabet proved to be an enormous advantage in the process because, in contrast to logographic writing systems, it allowed the type-setter to represent any text with a theoretical minimum of only around two dozen different letters.

[27] Considered the most important advance in the history of the book prior to printing itself, the codex had completely replaced the ancient scroll at the onset of the Middle Ages (AD 500).

The introduction of water-powered paper mills, the first certain evidence of which dates to 1282,[30] allowed for a massive expansion of production and replaced the laborious handcraft characteristic of both Chinese[31] and Muslim papermaking.

[32] Papermaking centres began to multiply in the late 13th century in Italy, reducing the price of paper to one-sixth of parchment and then falling further.

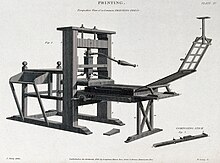

The frisket is a slender frame-work, covered with coarse paper, on which an impression is first taken; the whole of the printed part is then cut out, leaving apertures exactly corresponding with the pages of type on the carriage of the press.

The frisket when folded on to the tympans, and both turned down over the forme of types and run in under the platten, preserves the sheet from contact with any thing but the inked surface of the types, when the pull, which brings down the screw and forces the platten to produce the impression, is made by the pressman who works the lever,—to whom is facetiously given the title of "the practitioner at the bar.".

His type case is estimated to have contained around 290 separate letter boxes, most of which were required for special characters, ligatures, punctuation marks, and so forth.

[45] A later work, the Mainz Psalter of 1453, presumably designed by Gutenberg but published under the imprint of his successors Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer, had elaborate red and blue printed initials.

[48] Much later, printed literature played a major role in rallying support, and opposition, during the lead-up to the English Civil War, and later still the American and French Revolutions through newspapers, pamphlets and bulletins.

[52] As early as 1480, there were printers active in 110 different places in Germany, Italy, France, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, England, Bohemia and Poland.

[57] The rapidity of typographical text production, as well as the sharp fall in unit costs, led to the issuing of the first newspapers (see Relation) which opened up an entirely new field for conveying up-to-date information to the public.

[citation needed] Over the next 200 years, the wider availability of printed materials led to a dramatic rise in the adult literacy rate throughout Europe.

[67] The publication of trade-related manuals and books teaching techniques like double-entry bookkeeping increased the reliability of trade and led to the decline of merchant guilds and the rise of individual traders.

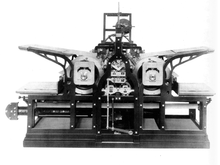

[68] At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the mechanics of the hand-operated Gutenberg-style press were still essentially unchanged, although new materials in its construction, amongst other innovations, had gradually improved its printing efficiency.

By 1800, Lord Stanhope had built a press completely from cast iron which reduced the force required by 90%, while doubling the size of the printed area.

The steam-powered rotary printing press, invented in 1843 in the United States by Richard M. Hoe,[72] ultimately allowed millions of copies of a page in a single day.

Mass production of printed works flourished after the transition to rolled paper, as continuous feed allowed the presses to run at a much faster pace.