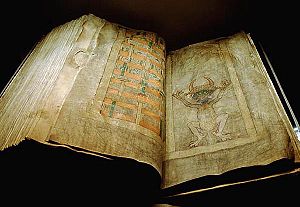

Codex

Technically, the vast majority of modern books use the codex format of a stack of pages bound at one edge, along the side of the text.

The gradual replacement of the scroll by the codex has been called the most important advance in book making before the invention of the printing press.

[11] The change from rolls to codices roughly coincides with the transition from papyrus to parchment as the preferred writing material, but the two developments are unconnected.

[12] Technically, even modern notebooks and paperbacks are codices, but publishers and scholars reserve the term for manuscript (hand-written) books produced from late antiquity until the Middle Ages.

Two ancient polyptychs, a pentaptych and octoptych excavated at Herculaneum, used a unique connecting system that presages later sewing on of thongs or cords.

[15][page range too broad] A first evidence of the use of papyrus in codex form comes from the Ptolemaic period in Egypt, as a find at the University of Graz shows.

[16][17] Julius Caesar may have been the first Roman to reduce scrolls to bound pages in the form of a note-book, possibly even as a papyrus codex.

[18] At the turn of the 1st century AD, a kind of folded parchment notebook called pugillares membranei in Latin became commonly used for writing in the Roman Empire.

He wrote a series of five couplets meant to accompany gifts of literature that Romans exchanged during the festival of Saturnalia.

In another poem by Martial, the poet advertises a new edition of his works, specifically noting that it is produced as a codex, taking less space than a scroll and being more comfortable to hold in one hand.

"[23] Early codices of parchment or papyrus appear to have been widely used as personal notebooks, for instance in recording copies of letters sent (Cicero Fam.

"Official documents and deluxe manuscripts [in the late Middle Ages] were written in gold and silver ink on parchment...dyed or painted with costly purple pigments as an expression of imperial power and wealth.

Despite this comparison, a fragment of a non-Christian parchment codex of Demosthenes' De Falsa Legatione from Oxyrhynchus in Egypt demonstrates that the surviving evidence is insufficient to conclude whether Christians played a major or central role in the development of early codices—or if they simply adopted the format to distinguish themselves from Jews.

[26] The earliest surviving fragments from codices come from Egypt, and are variously dated (always tentatively) towards the end of the 1st century or in the first half of the 2nd.

This group includes the Rylands Library Papyrus P52, containing part of St John's Gospel, and perhaps dating from between 125 and 160.

[4] The codices of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica (Mexico and Central America) had a similar appearance when closed to the European codex, but were instead made with long folded strips of either fig bark (amatl) or plant fibers, often with a layer of whitewash applied before writing.

There are significant codices produced in the colonial era, with pictorial and alphabetic texts in Spanish or an indigenous language such as Nahuatl.

There were intermediate stages, such as scrolls folded concertina-style and pasted together at the back and books that were printed only on one side of the paper.

[30] This replaced traditional Chinese writing mediums such as bamboo and wooden slips, as well as silk and paper scrolls.

[32][failed verification] The initial phase of this evolution, the accordion-folded palm-leaf-style book, most likely came from India and was introduced to China via Buddhist missionaries and scriptures.

The next evolutionary step was to cut the folios and sew and glue them at their centers, making it easier to use the papyrus or vellum recto-verso as with a modern book.

For example, the average calfskin can provide three-and-a-half medium sheets of writing material, which can be doubled when they are folded into two conjoint leaves, also known as a bifolium.

Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham point out, in "Introduction to Manuscript Studies", that "the quire was the scribe's basic writing unit throughout the Middle Ages":[35]: 14 Pricking is the process of making holes in a sheet of parchment (or membrane) in preparation of it ruling.

This was not the same style used in the British Isles, where the membrane was folded so that it turned out an eight-leaf quire, with single leaves in the third and sixth positions.

[citation needed] The materials codices are made with are their support, and include papyrus, parchment (sometimes referred to as membrane or vellum), and paper.

[38] The structure of a codex includes its size, format/ordinatio[38] (its quires or gatherings),[39] consisting of sheets folded a number of times, often twice- a bifolio,[40] sewing, bookbinding, and rebinding.

The apparatus of books for scholars became more elaborate during the 13th and 14th centuries when chapter, verse, page numbering, marginalia finding guides, indexes, glossaries, and tables of contents were developed.

[38] By a close examination of the physical attributes of a codex, it is sometimes possible to match up long-separated elements originally from the same book.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek , Munich.