Gyromitrin

Gyromitrin is a toxin and carcinogen present in several members of the fungal genus Gyromitra, like G. esculenta.

Poisonings related to consumption of the false morel Gyromitra esculenta, a highly regarded fungus eaten mainly in Finland and by some in parts of Europe and North America, had been reported for at least a hundred years.

Experts speculated the reaction was more of an allergic one specific to the consumer, or a misidentification, rather than innate toxicity of the fungus, due to the wide range in effects seen.

[2] The identity of the toxic constituents of Gyromitra species eluded researchers until 1968, when N-methyl-N-formylhydrazone was isolated by German scientists List and Luft and named gyromitrin.

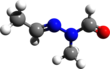

[3][contradictory] Gyromitrin is a volatile, water-soluble hydrazine compound that can be hydrolyzed in the body into monomethylhydrazine (MMH) through the intermediate N-methyl-N-formylhydrazine.

This reduces production of the neurotransmitter GABA via decreased activity of glutamic acid decarboxylase,[6] which gives rise to the neurological symptoms.

[8][9] Inhibition of diamine oxidase (histaminase) elevates histamine levels, resulting in headaches, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Tests of administering gyromitrin to mice to observe the correlation between the formation of MMH and stomach pH have been performed.

The conclusions drawn were that the formation of MMH in a stomach is likely a result of acid hydrolysis of gyromitrin rather than enzymatic metabolism.

[4] Based on this animal experimentation, it is reasonable to infer that a more acidic stomach environment would transform more gyromitrin into MMH, independent of the species in which the reaction is occurring.

Species in which gyromitrin's presence is suspected, but not proven, include G. californica, G. caroliniana, G. korfii, and G. sphaerospora, in addition to Disciotis venosa and Sarcosphaera coronaria.

[16] The early methods developed for the determination of gyromitrin concentration in mushroom tissue were based on thin-layer chromatography and spectrofluorometry, or the electrochemical oxidation of hydrazine.

[24] Toxic effects from gyromitrin may also be accumulated from sub-acute and chronic exposure due to "professional handling"; symptoms include pharyngitis, bronchitis, and keratitis.

[18] Treatment is mainly supportive; gastric decontamination with activated charcoal may be beneficial if medical attention is sought within a few hours of consumption.

[20] Monitoring of biochemical parameters such as methemoglobin levels, electrolytes, liver and kidney function, urinalysis, and complete blood count is undertaken and any abnormalities are corrected.

The identity of the toxin found in Gyromitra was not known until List and Luft of Germany were able to isolate and identify the structure of gyromitrin from these mushrooms in 1968.

[30] As gyromitrin is not especially stable, most poisonings apparently occur from the consumption of the raw or insufficiently cooked "false morel" mushrooms.

[31] Monomethylhydrazine,[32] as well as its precursors methylformylhydrazine[33][34] and gyromitrin[35] and raw Gyromitra esculenta,[36] have been shown to be carcinogenic in experimental animals.

[37][38] Although Gyromitra esculenta has not been observed to cause cancer in humans,[39] it is possible there is a carcinogenic risk for people who ingest these types of mushrooms.

[40] At least 11 different hydrazines have been isolated from Gyromitra esculenta, and it is not known if the potential carcinogens can be completely removed by parboiling.