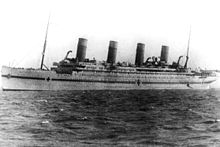

HMHS Britannic

On the morning of 21 November 1916 she hit a naval mine of the Imperial German Navy near the Greek island of Kea and sank 55 minutes later, killing 30 of 1,066 people on board; the 1,036 survivors were rescued from the water and lifeboats.

[3] After the War, the White Star Line was compensated for the loss of Britannic by the award of SS Bismarck as part of postwar reparations; she entered service as RMS Majestic.

With Britannic, these changes made before launch included increasing the ship's beam to 94 feet (29 m) to allow for a double hull along the engine and boiler rooms and raising six out of the 15 watertight bulkheads up to B Deck.

[19][20][21][22] Tom McCluskie stated that in his capacity as archive manager and historian at Harland and Wolff, he "never saw any official reference to the name Gigantic being used or proposed for the third of the Olympic-class vessels".

[29] Reusing Olympic's space saved the shipyard time and money by not clearing out a third slip similar in size to those used for the two previous vessels.

[31] The following month, the Admiralty decided to use recently requisitioned passenger liners as troop transports in the Gallipoli Campaign (also called the Dardanelles service).

As the Gallipoli landings proved to be disastrous and the casualties mounted, the need for large hospital ships for treatment and evacuation of wounded became evident.

[citation needed] Repainted white with large red crosses and a horizontal green stripe, she was renamed HMHS (His Majesty's Hospital Ship) Britannic[30] and placed under the command of Captain Charles Alfred Bartlett.

[32] On 23 December, she left Liverpool to join the port of Mudros on the island of Lemnos on the Aegean Sea to bring back sick and wounded soldiers.

[38] At the end of her military service on 6 June 1916, Britannic returned to Belfast to undergo the necessary modifications for transforming her into a transatlantic passenger liner.

The reaction in the dining room was immediate; doctors and nurses left instantly for their posts but not everybody reacted the same way, as further aft, the power of the explosion was less felt, and many thought the ship had hit a smaller boat.

The captain ordered the port shaft driven at a higher speed than the starboard side, which helped the ship move towards Kea.

Major Harold Priestley gathered his detachments from the Royal Army Medical Corps to the back of the A deck and inspected the cabins to ensure no one was left behind.

At this point, Bartlett concluded that the rate at which Britannic was sinking had slowed so he called a halt to the evacuation and ordered the engines restarted in the hope that he might still be able to beach the ship.

As Britannic's length was greater than the depth of the water, the impact caused major structural damage to the bow before she slipped completely beneath the waves at 09:07, 55 minutes after the explosion.

[66] Some 150 had made it to Korissia, Kea, where surviving doctors and nurses from Britannic were trying to save the injured, using aprons and pieces of lifebelts to make dressings.

HMS Foxhound arrived at 11:45 and, after sweeping the area, anchored in the small port at 13:00 to offer medical assistance and take on board the remaining survivors.

Foxhound departed for Piraeus at 14:15 while Foresight remained to arrange the burial on Kea of RAMC Sergeant William Sharpe, who had died of his injuries.

[70] In November 2006, Britannic researcher Michail Michailakis discovered that one of the 45 unidentified graves in the New British Cemetery in the town of Hermoupolis on the island of Syros contained the remains of a soldier collected from the church of Ag.

[71] When the remains were moved to the new cemetery at Syros in June 1921, it was found that there was no record relating this name with the loss of the ship, and the grave was registered as unidentified.

[76] The B Deck included a hair salon, post office, and redesigned deluxe Parlour Suites, dubbed Saloons in the Builder's Plans.

[82][73] In filming the expedition, Cousteau also held conference on camera with several surviving personnel from the ship including Sheila MacBeth Mitchell, a survivor of the sinking.

[85] The giant liner lies on her starboard side relatively intact, hiding the large hole that was torn open by the mine.

[88] In November 1997, an international team of divers led by Kevin Gurr used open-circuit trimix diving techniques to visit and film the wreck in the newly available DV digital video format.

[89][90] Using diver propulsion vehicles, the team made more man-dives to the wreck and produced more images than ever before, including video of four telegraphs, a helm and a telemotor on the captain's bridge.

[94] In 2006, an expedition, funded and filmed by the History Channel, brought together fourteen skilled divers to help determine what caused the quick sinking of Britannic.

One last dive was to be attempted on Britannic's boiler room, but it was discovered that photographing this far inside the wreck would lead to violating a permit issued by the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, a department within the Greek Ministry of Culture.

[95] In 2012, on an expedition organised by Alexander Sotiriou and Paul Lijnen, divers using rebreathers installed and recovered scientific equipment used for environmental purposes, to determine how fast bacteria are eating Britannic's iron compared to Titanic.

[97] Having her career cut short in wartime, never having entered commercial service, and having had few victims, Britannic did not experience the same notoriety as her sister ship Titanic.

[citation needed] A BBC2 documentary, Titanic's Tragic Twin – the Britannic Disaster, was broadcast on 5 December 2016; presented by Kate Humble and Andy Torbet, it used up-to-date underwater film of the wreck and spoke to relatives of survivors.