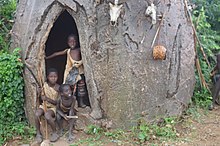

Hadza people

As descendants of Tanzania's aboriginal, pre-Bantu expansion hunter-gatherer population, they have probably occupied their current territory for thousands of years with relatively little modification to their basic way of life until the last century.

Since the first European contact in the late 19th century, governments and missionaries have made many attempts to settle the Hadza by introducing farming and Christianity.

Traditionally, they primarily forage for food, eating mostly honey, tubers, fruit, and, especially in the dry season, meat.

The akakaanebee did not possess tools or fire; they hunted game by running it down until it fell dead; they ate meat raw.

When discussing the hamayishonebee epoch, people often mention specific names and places and can say approximately how many generations ago events occurred.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the area has been continuously occupied by hunter-gatherers much like the Hadza since at least the beginning of the Later Stone Age, 50,000 years ago.

[17] Each of these expansions of farming and herding peoples displaced earlier populations of hunter-gatherers, who were at a demographic and technological disadvantage and vulnerable to the loss of environmental resources (i.e., foraging areas and habitats for game) to farmland and pastures.

[18] Groups such as the Hadza and the Sandawe are remnants of indigenous hunter-gatherer populations that were once much more widespread, and they are under continued pressure from the expansion of agriculture into their traditional lands.

They viewed them as backward, lacking a "real language," and made up of the dispossessed of neighboring tribes that had fled into the forest out of poverty or because they committed a crime.

The earliest mention of the Hadza in a written account is in German explorer Oscar Baumann's Durch Massailand zur Nilquelle (1894).

Early on, Obst noted a distinction between what he considered the 'pure' Hadza (those subsisting purely by hunting and gathering) and those that lived with the Isanzu and practiced some cultivation.

Generally, the Hadza willingly settle as long as provided food stocks last, then leave and resume their traditional hunter-gatherer lives when the provisions run out; few have adopted farming for sustenance.

[citation needed] Of the four villages built for the Hadza since 1965, two (Yaeda Chini and Munguli) are now inhabited by the Isanzu, Iraqw, and Datooga.

Another, Mongo wa Mono, established in 1988, is sporadically occupied by Hadza groups who stay there for a few months at a time, either farming, foraging, or using the food given to them by missionaries.

People access the western area by crossing the southern end of the lake, which is the first part to dry up, or by following the escarpment of the Serengeti Plateau around the northern shore.

The Hadza have traditionally foraged outside of these areas, in the Yaeda Valley, on the slopes of Mount Oldeani north of Mang'ola, and up onto the Serengeti Plains.

Ernst Fehr and Urs Fischbacher point out that the Hadza people “exhibit a considerable amount of altruistic punishment” to organize these tribes.

A 2001 anthropological study on modern foragers found that the Hadza men and women had an average life expectancy at birth of 33.

Women forage in larger parties and usually bring home berries, baobab fruit,[39] and tubers, depending on availability.

[40] During the dry season, men often hunt in pairs and spend entire nights lying in wait by waterholes, hoping to shoot animals that approach for a night-time drink with poisoned bows and arrows.

The Hadza hunt and eat a variety of animals including impala, dik-dik, kudu, baboon, vervet monkey, bush baby, shrew, warthog, bushpig and various birds.

The human eats or carries away most of the liquid honey, while the honeyguide consumes beeswax that may be left adhering to the tree, spat out, or otherwise discarded at the site of acquisition.

[21] Honey represents a substantial portion of the Hadza diet (~10-20% of calories), which is similar to many other hunter-gatherer societies living in the tropics.

[45] Honey likely carried an evolutionary advantage via an improvement in the energy density of the human diet when it contained bee products.

They also hold rituals such as the monthly epeme dance for men at the new moon and the less frequent maitoko circumcision and coming-of-age ceremony for women.

He wears a headdress of dark ostrich feathers, bells on one of his ankles, a rattle in his hand, and a long black cape on his back.

He stamps his right foot hard on the ground in time with the women's singing, causing the bells to ring while marking the beat of the music with his rattle.

[47] These figures are described as making crucial decisions about the animals and humans by choosing their food and environment,[48] giving people access to fire, and creating the capability of sitting.

"[53] Indaya, the man who went to the Isanzu territory after his death and returned,[54] plays the role of a culture hero: he introduces customs and goods to the Hadza.

Finally, the god Haine determined a course of justice: he warned the people, revealed the boy's malevolent deed, and changed the giant into a big white clam.