Hand

A hand is a prehensile, multi-fingered appendage located at the end of the forearm or forelimb of primates such as humans, chimpanzees, monkeys, and lemurs.

Fingers contain some of the densest areas of nerve endings in the body, and are the richest source of tactile feedback.

Likewise, the ten digits of two hands and the twelve phalanges of four fingers (touchable by the thumb) have given rise to number systems and calculation techniques.

The scientific use of the term hand in this sense to distinguish the terminations of the front paws from the hind ones is an example of anthropomorphism.

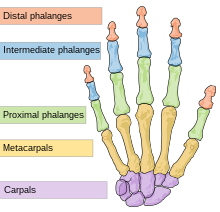

The heads of the metacarpals will each in turn articulate with the bases of the proximal phalanx of the fingers and thumb.

[11] Together with the phalanges of the fingers and thumb these metacarpal bones form five rays or poly-articulated chains.

Because supination and pronation (rotation about the axis of the forearm) are added to the two axes of movements of the wrist, the ulna and radius are sometimes considered part of the skeleton of the hand.

There are numerous sesamoid bones in the hand, small ossified nodes embedded in tendons; the exact number varies between people:[7] whereas a pair of sesamoid bones are found at virtually all thumb metacarpophalangeal joints, sesamoid bones are also common at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb (72.9%) and at the metacarpophalangeal joints of the little finger (82.5%) and the index finger (48%).

Because the proximal arch simultaneously has to adapt to the articular surface of the radius and to the distal carpal row, it is by necessity flexible.

These ligaments also form the carpal tunnel and contribute to the deep and superficial palmar arches.

Together with the index and middle finger, it forms the dynamic tridactyl configuration responsible for most grips not requiring force.

The ring and little fingers are more static, a reserve ready to interact with the palm when great force is needed.

The extensors are located on the back of the forearm and are connected in a more complex way than the flexors to the dorsum of the fingers.

The median nerve supplies the flexors of the wrist and digits, the abductors and opponens of the thumb, the first and second lumbrical.

[15] All muscles of the hand are innervated by the brachial plexus (C5–T1) and can be classified by innervation:[16] The radial nerve supplies the skin on the back of the hand from the thumb to the ring finger and the dorsal aspects of the index, middle, and half ring fingers as far as the proximal interphalangeal joints.

The median nerve supplies the palmar side of the thumb, index, middle, and half ring fingers.

Dorsal branches innervates the distal phalanges of the index, middle, and half ring fingers.

All parts of the skin involved in grasping are covered by papillary ridges (fingerprints) acting as friction pads.

On the dorsal side, the skin can be moved across the hand up to 3 cm (1.2 in); an important input the cutaneous mechanoreceptors.

Hominidae (great apes including humans) acquired an erect bipedal posture about 3.6 million years ago, which freed the hands from the task of locomotion and paved the way for the precision and range of motion in human hands.

[22] Functional analyses of the features unique to the hand of modern humans have shown that they are consistent with the stresses and requirements associated with the effective use of paleolithic stone tools.

[23] It is possible that the refinement of the bipedal posture in the earliest hominids evolved to facilitate the use of the trunk as leverage in accelerating the hand.

[25] The recent evolution of the human hand is thus a direct result of the development of the central nervous system, and the hand, therefore, is a direct tool of our consciousness—the main source of differentiated tactile sensations—and a precise working organ enabling gestures—the expressions of our personalities.

[27] Humans did not evolve from knuckle-walking apes,[28] and chimpanzees and gorillas independently acquired elongated metacarpals as part of their adaptation to their modes of locomotion.

This suggests that the derived changes in modern humans and Neanderthals did not evolve until 2.5 to 1.5 million years ago or after the appearance of the earliest Acheulian stone tools, and that these changes are associated with tool-related tasks beyond those observed in other hominins.

[30] The thumbs of Ardipithecus ramidus, an early hominin, are almost as robust as in humans, so this may be a primitive trait, while the palms of other extant higher primates are elongated to the extent that some of the thumb's original function has been lost (most notably in highly arboreal primates such as the spider monkey).

[29] There is a hypothesis suggesting the form of the modern human hand is especially conducive to the formation of a compact fist, presumably for fighting purposes.

[31][32][33] However, this is not widely accepted to be one of the primary selective pressures acting on hand morphology throughout human evolution, with tool use and production being thought to be far more influential.

Red: one of the oblique arches

Brown: one of the longitudinal arches of the digits

Dark green: transverse carpal arch

Light green: transverse metacarpal arch