Harriet Jacobs

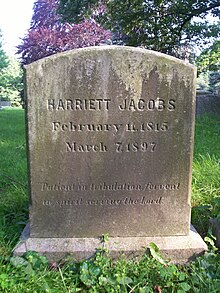

Harriet Jacobs[a] (1813 or 1815[b] – March 7, 1897) was an African-American abolitionist and writer whose autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent, is now considered an "American classic".

After staying there for seven years, she finally managed to escape to the free North, where she was reunited with her children Joseph and Louisa Matilda and her brother John S. Jacobs.

During and immediately after the American Civil War, she travelled to Union-occupied parts of the Confederate South together with her daughter, organizing help and founding two schools for fugitive and freed slaves.

[c] Under the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, both Harriet and her brother John were enslaved at birth by the tavern keeper's family, as a mother's status was passed to her children.

When Jacobs fell in love with a free black man who wanted to buy her freedom and marry her, Norcom intervened and forbade her to continue with the relationship.

After a short time, Jacobs had to hide in a swamp near the town, and at last she found refuge in a "tiny crawlspace"[25] under the roof of her grandmother's house.

[29] Norcom reacted by selling Jacobs's children and her brother John to a slave trader demanding that they should be sold in a different state, thus expecting to separate them forever from their mother and sister.

[42] The former "slave girl" who had never been to school, and whose life had mostly been confined by the struggle for her own survival in dignity and that of her children, now found herself in circles that were about to change America through their - by the standards of the time - radical set of ideas.

The Reading Room was in the same building as the newspaper The North Star, run by Frederick Douglass, who today is considered the most influential African American of his century.

Jacobs, in whose autobiography the constant danger for herself and other enslaved mothers of being separated from their children is an important theme, spoke to her employer of the sacrifice that letting go of her baby daughter meant to her.

[45] In February 1852, Jacobs read in the newspaper that her legal owner, the daughter of the recently deceased Norcom, had arrived at a New York Hotel together with her husband, obviously intending to re-claim their fugitive slave.

Post later described how difficult it was for Jacobs to tell of her traumatic experiences: "Though impelled by a natural craving for human sympathy, she passed through a baptism of suffering, even in recounting her trials to me.

Jacobs's brother had for some time been urging her to do so, and she felt a moral obligation to tell her story to help build public support for the antislavery cause and thus save others from suffering a similar fate.

The shame caused by this memory and the resulting fear of having to tell her story had been the reason for her initially avoiding contact with the abolitionist movement her brother John had joined in the 1840s.

Before Stowe's answer arrived, Jacobs read in the papers that the famous author, whose novel Uncle Tom's Cabin, published in 1852, had become an instant bestseller, was going to England.

In a letter to Post, she analyzed the racist thinking behind Stowe's remark on Louisa with bitter irony: "what a pity we poor blacks can[']t have the firmness and stability of character that you white people have."

With N.P.Willis being largely forgotten today,[56] Yellin comments on the irony of the situation: "Idlewild had been conceived as a famous writer's retreat, but its owner never imagined that it was his children's nurse who would create an American classic there".

Even in this letter she mentions the shame that made writing her story difficult for herself: "as much pleasure as it would afford me and as great an honor as I would deem it to have your name associated with my Book –Yet believe me dear friend[,] there are many painful things in it – that make me shrink from asking the sacrifice from one so good and pure as your self–.

Jacobs confessed to Amy Post, that after suffering another rejection from Stowe, she could hardly bring herself to asking another famous writer, but she "resolved to make my last effort".

[69] The London Daily News wrote in 1862, that Linda Brent was a true "heroine", giving an example "of endurance and persistency in the struggle for liberty" and "moral rectitude".

Originally, Jacobs had planned to follow the example her brother John S. had set nearly two decades ago and become an abolitionist speaker, but now she saw that helping the Contrabands would mean rendering her race a service more urgently needed.

Together with Quaker Julia Wilbur, the teacher, feminist and abolitionist, whom she had already known in Rochester, she was distributing clothes and blankets and at the same time struggling with incompetent, corrupt, or openly racist authorities.

Together with the other participants she watched the parade of the newly created 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment,[76] consisting of black soldiers led by white officers.

Jacobs expressed her joy and pride in a letter to Lydia Maria Child: "How my heart swelled with the thought that my poor oppressed race were to strike a blow for freedom !"

In the fall of 1863 her daughter Louisa Matilda who had been trained as a teacher, came to Alexandria in the company of Virginia Lawton, a black friend of the Jacobs family.

In the National Anti-Slavery Standard, Harriet Jacobs explained that it was not disapproval of white teachers that made her fight for the school being controlled by the black community.

[80] On August 1, 1864, she delivered the speech on occasion of the celebration of the British West Indian Emancipation[i] in front of the African American soldiers of a military hospital in Alexandria.

The land question together with the unjust labor contracts forced on the former slaves by their former enslavers with the help of the army, are an important subject in Jacobs's reports from Georgia.

Epistle to the Romans, 12:11–12)[90] Prior to Jean Fagan Yellin's research in the 1980s, the accepted academic opinion, voiced by such historians as John Blassingame, was that Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was a fictional novel written by Lydia Maria Child.

"[94] In an interview, Colson Whitehead, author of the best selling novel, The Underground Railroad, published in 2016, said: "Harriet Jacobs is a big referent for the character of Cora",[95] the heroine of the novel.