Health care system in Japan

Payment for personal medical services is offered by a universal health care insurance system that provides relative equality of access, with fees set by a government committee.

The modern Japanese health care system started to develop just after the Meiji Restoration with the introduction of Western medicine.

[4] In the late 1980s, government and professional circles were considering changing the system so that primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care would be clearly distinguished within each geographical region.

Around the same time, there were nearly 191,400 physicians, 66,800 dentists, and 333,000 nurses, plus more than 200,000 people licensed to practice massage, acupuncture, moxibustion, and other East Asian therapeutic methods.

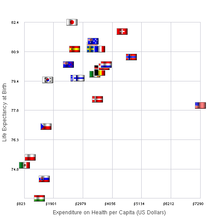

In 2008, Japan spent about 8.2% of the nation's gross domestic product (GDP), or US$2,859.7 or 405,737.84 Yen per capita, on health, ranking 20th among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

[6] According to 2018 data, share of gross domestic products rose to 10.9% of GDP, overtaking the OECD average of 8.8%.

[6] Comparisons based on this number may be difficult to make, however, since 34% of patients were admitted to hospitals for longer than 30 days even in beds that were classified as acute care.

[7] Unlike many countries, there is no system of general practitioners in Japan, instead, patients go straight to specialists, often working in clinics.

In an article titled "Does Japanese Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Qualify as a Global Leader?

"[22] Masami Ochi of Nippon Medical School points out that Japanese coronary bypass surgeries surpass those of other countries in multiple criteria.

Despite reforms, Japan's psychiatric hospitals continue to largely rely on outdated methods of patient control, with their rates of compulsory medication, isolation (solitary confinement) and physical restraints (tying patients to beds) much higher than in other countries.

[24] High levels of deep vein thrombosis have been found in restrained patients in Japan, which can lead to disability and death.

[27] The 47 local government prefectures have some responsibility for overseeing the quality of health care, but there is no systematic collection of treatment or outcome data.

In 2015 Japan introduced a law to require hospitals to conduct reviews of patient care for any unexpected deaths and to provide the reports to the next of kin and a third party organization.

[31] However, the increased number of hospital visits per capita compared to other nations and the generally good overall outcome suggests the rate of adverse medical events are not higher than in other countries.

As mentioned above, costs in Japan tend to be quite low compared to those in other developed countries, but utilization rates are much higher.

Some patients with mild illnesses tend to go straight to the hospital emergency departments rather than accessing more appropriate primary care services.

This causes a delay in helping people who have more urgent and severe conditions who need to be treated in the hospital environment.

A government survey for 2007, which got a lot of attention when it was released in 2009, cited several such incidents in the Tokyo area, including the case of an elderly man who was turned away by 14 hospitals before dying 90 minutes after being finally admitted,[37] and that of a pregnant woman complaining of a severe headache being refused admission to seven Tokyo hospitals and later dying of an undiagnosed brain hemorrhage after giving birth.

[38] The so-called "tarai mawashi" (ambulances being rejected by multiple hospitals before an emergency patient is admitted) has been attributed to several factors such as medical reimbursements set so low that hospitals need to maintain very high occupancy rates to stay solvent, hospital stays being cheaper for the patient than low-cost hotels, the shortage of specialist doctors and low-risk patients with minimal need for treatment flooding the system.

Health insurance is, in principle, mandatory for residents of Japan, but there is no penalty for the 10% of individuals who choose not to comply, making it optional in practice.

Supplementary private health insurance is available only to cover the co-payments or non-covered costs and has a fixed payment per day in hospital or per surgery performed, rather than per actual expenditure.

[45][46] There is a separate system of insurance - Kaigo-Hoken (介護保険) - for long-term care, run by the municipal governments.

[49] Today, Japan has the severe problem of paying for rising medical costs, benefits that are not equal from one person to another and even burdens on each of the nation's health insurance programs.

[50] One of the ways Japan has improved its healthcare more recently is by passing the Industrial Competitiveness Enhancement Action Plan.