Origami

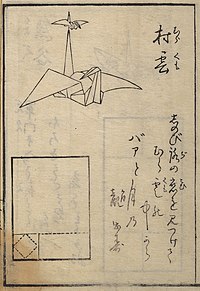

Traditional Japanese origami, which has been practiced since the Edo period (1603–1868), has often been less strict about these conventions, sometimes cutting the paper or using nonsquare shapes to start with.

Before that, paper folding for play was known by a variety of names, including "orikata" or "origata" (折形), "orisue" (折据), "orimono" (折物), "tatamigami" (畳紙) and others.

The Ise clan presided over the decorum of the inside of the palace of the Ashikaga Shogunate, and in particular, Ise Sadachika (ja:伊勢貞親) during the reign of the eighth Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa (足利義政), greatly influenced the development of the decorum of the daimyo and samurai classes, leading to the development of various stylized forms of ceremonial origami.

The "noshi" wrapping, and the folding of female and male butterflies, which are still used for weddings and celebrations, are a continuation and development of a tradition that began in the Muromachi period.

[1][2][11] A reference in a poem by Ihara Saikaku from 1680 describes the origami butterflies used during Shinto weddings to represent the bride and groom.

After this period, this genre declined and was mostly forgotten; historian Joan Sallas attributes this to the introduction of porcelain, which replaced complex napkin folds as a dinner-table status symbol among nobility.

[17] When Japan opened its borders in the 1860s, as part of a modernization strategy, they imported Fröbel's Kindergarten system—and with it, German ideas about paperfolding.

Before this, traditional Japanese sources use a variety of starting shapes, often had cuts, and if they had color or markings, these were added after the model was folded.

Akira Yoshizawa in particular was responsible for a number of innovations, such as wet-folding and the Yoshizawa–Randlett diagramming system, and his work inspired a renaissance of the art form.

[20] During the 1980s a number of folders started systematically studying the mathematical properties of folded forms, which led to a rapid increase in the complexity of origami models.

The "new origami," which distinguishes it from old craft practices, has had a rapid evolution due to the contribution of computational mathematics and the development of techniques such as box-pleating, tessellations and wet-folding.

Artists like Robert J. Lang, Erik Demaine, Sipho Mabona, Giang Dinh, Paul Jackson, and others, are frequently cited for advancing new applications of the art.

The computational facet and the interchanges through social networks, where new techniques and designs are introduced, have raised the profile of origami in the 21st century.

It is commonly colored on one side and white on the other; however, dual coloured and patterned versions exist and can be used effectively for color-changed models.

Artisan papers such as unryu, lokta, hanji[citation needed], gampi, kozo, saa, and abaca have long fibers and are often extremely strong.

One example is Robert Lang's instrumentalists; when the figures' heads are pulled away from their bodies, their hands will move, resembling the playing of music.

[citation needed] This style originated from some Chinese refugees while they were detained in America and is also called Golden Venture folding from the ship they came on.

[citation needed] Wet-folding is an origami technique for producing models with gentle curves rather than geometric straight folds and flat surfaces.

During the 1960s, Shuzo Fujimoto was the first to explore twist fold tessellations in any systematic way, coming up with dozens of patterns and establishing the genre in the origami mainstream.

Around the same time period, Ron Resch patented some tessellation patterns as part of his explorations into kinetic sculpture and developable surfaces, although his work was not known by the origami community until the 1980s.

Tessellation artists include Polly Verity (Scotland); Joel Cooper, Christine Edison, Ray Schamp and Goran Konjevod from the US; Roberto Gretter (Italy); Christiane Bettens (Switzerland); Carlos Natan López (Mexico); and Jorge C. Lucero (Brazil).

[30] Teabag folding is credited to Dutch artist Tiny van der Plas, who developed the technique in 1992 as a papercraft art for embellishing greeting cards.

[32] The problem of rigid origami ("if we replaced the paper with sheet metal and had hinges in place of the crease lines, could we still fold the model?")

This method of origami design was developed by Robert Lang, Meguro Toshiyuki and others, and allows for the creation of extremely complex multi-limbed models such as many-legged centipedes, human figures with a full complement of fingers and toes, and the like.

The use of polygonal shapes other than circles is often motivated by the desire to find easily locatable creases (such as multiples of 22.5 degrees) and hence an easier folding sequence as well.

As a result, the crease pattern that arises from this method contains only 45 and 90 degree angles, which often makes for a more direct folding sequence.

[34] TreeMaker allows new origami bases to be designed for special purposes[35] and Oripa tries to calculate the folded shape from the crease pattern.

It has been claimed that all commercial rights to designs and models are typically reserved by origami artists; however, the degree to which this can be enforced has been disputed.

However, a court in Japan has asserted that the folding method of an origami model "comprises an idea and not a creative expression, and thus is not protected under the copyright law".

From a global perspective, the term 'origami' refers to the folding of paper to shape objects for entertainment purposes, but it has historically been used in various ways in Japan.