Diadochi

: diadochos) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC.

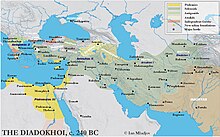

The Wars of the Diadochi mark the beginning of the Hellenistic period from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indus River Valley.

[2] In ancient Greek, diadochos[3] is a noun (substantive or adjective) formed from the verb, diadechesthai, "succeed to,"[4] a compound of dia- and dechesthai, "receive.

Philip is said to have wept for joy when Alexander performed a feat of which no one else was capable, taming the wild horse, Bucephalus, at his first attempt in front of a skeptical audience including the king.

[citation needed] The inebriated Philip, rising to his feet and drawing his sword to defend Attalus, promptly fell.

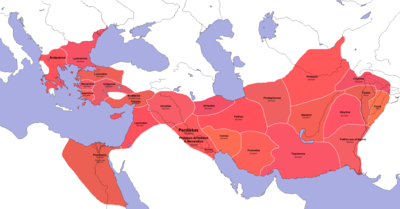

When Alexander the Great died on June 10, 323 BC, he left behind a huge empire which comprised many essentially independent territories.

Alexander's empire stretched from his homeland of Macedon itself, along with the Greek city-states that his father had subdued, to Bactria and parts of India in the east.

The hetairoi were a special cavalry unit composed of general officers without fixed rank, whom Alexander could assign where needed.

After the revolt of his army at Opis on the Tigris in 324, Alexander ordered Craterus to command the veterans as they returned home to Macedonia.

Though his distance from Babylon prevented him from participating in the distribution of power, Craterus hastened to Macedonia to assume the protection of Alexander's family.

Originally the Epigoni (/ɪˈpɪɡənaɪ/; from Ancient Greek: Ἐπίγονοι "offspring") were the sons of the Argive heroes who had fought in the first Theban war.

Perdiccas, summoned a council of the great men of Alexander's court to appoint satraps for the parts of the Empire in the partition of Babylon.

Macedon and the rest of Greece were to be jointly ruled by Antipater and Craterus, while Alexander's former secretary, Eumenes of Cardia, was to receive Cappadocia and Paphlagonia.

Antipater was relieved by a force sent by Leonnatus, who was killed in action, but the war did not come to an end until Craterus's arrival with a fleet to defeat the Athenians at the Battle of Crannon on September 5, 322 BC.

Meanwhile, Peithon suppressed a revolt of Greek settlers in the eastern parts of the Empire, and Perdiccas and Eumenes subdued Cappadocia.

Perdiccas' marriage to Alexander's sister Cleopatra led Antipater, Craterus, Antigonus, and Ptolemy to join in rebellion.

Although Eumenes defeated the rebels in Asia Minor, in a battle at which Craterus was killed, it was all for nought, as Perdiccas himself was murdered by his own generals Peithon, Seleucus, and Antigenes during an invasion of Egypt.

Ptolemy came to terms with Perdiccas's murderers, making Peithon and Arrhidaeus regents in his place, but soon these came to a new agreement with Antipater at the Partition of Triparadisus.

In effect, Antipater retained for himself control of Europe, while Antigonus, as leader of the largest army east of the Hellespont, held a similar position in Asia.

Polyperchon allied himself to Eumenes in Asia, but was driven from Macedonia by Cassander, and fled to Epirus with the infant king Alexander IV and his mother Roxana.

Soon after, though, the tide turned, and Cassander was victorious, capturing and killing Olympias, and attaining control of Macedon, the boy king, and his mother.

The cosmopolitan nature of Ptolemaic Egypt can be seen with the Rosetta Stone, an edict ordered by Ptolemy V Epiphanes (204–180 BC), would be written in three languages: Egyptian hieroglyphs, Coptic, and Greek.

However, the Ptolemaic rulers' insistence on the incorporation of Greek influences into Egyptian society led to many peasant revolts and uprisings throughout the course of the kingdom's existence.

In the formal "court" titulature of the Hellenistic empires ruled by dynasties we know as Diadochs, the title was not customary for the Monarch, but has actually been proven to be the lowest in a system of official rank titles, known as Aulic titulature, conferred – ex officio or nominatim – to actual courtiers and as an honorary rank (for protocol) to various military and civilian officials.

There is no uniform agreement concerning exactly which historical persons fit the description, or the territorial range over which the role was in effect, or the calendar dates of the period.

Their comprehensive histories of ancient Greece typically covering from prehistory to the Roman Empire ran into many volumes.

So large a number of them is neither verifiable nor probable, unless we either reckon up simple military posts or borrow from the list of foundations really established by his successors."

To Grote's assertion in the Preface to his work that the period "is of no interest in itself," but serves only to elucidate "the preceding centuries," Austin comments "Few nowadays would subscribe to this view.

A series of six (as of 2014) international symposia held at different universities 1997–2010 on the topics of the imperial Macedonians and their Diadochi have to a large degree solidified and internationalized Droysen's concepts.

[18] The 2010 symposium, entitled "The Time of the Diadochi (323-281 BC)," held at the University of A Coruña, Spain, represents the current concepts and investigations.