History of Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

[29] Alexander I, who Herodotus claimed was entitled proxenos ('host') and euergetes ('benefactor') by the Athenians, cultivated a close relationship with the Greeks following the Persian defeat and withdrawal, sponsoring the erection of statues at both major panhellenic sanctuaries at Delphi and Olympia.

[35] This led Perdiccas to seek alliances with Athens' rivals Sparta and Corinth, yet when his efforts were rejected he instead promoted the rebellion of nearby nominal Athenian allies in Chalcidice, winning over the important city of Potidaea.

[42] However, given Sitalces' huge Thracian invading force (allegedly 150,000 soldiers) and a nephew of Perdiccas II that he intended to place on the Macedonian throne after toppling the latter's regime, Athens must have become wary of acting on their supposed alliance since they failed to provide him with promised naval support.

[46] The massive combined force commanded by Arrhabaeus apparently caused the army of Perdiccas II to flee in haste before the battle began, which enraged the Spartans under Brasidas, who proceeded to snatch pieces of the Macedonian baggage train left unprotected.

[48] The treaty offered Athens economic concessions, but it also guaranteed internal stability in Macedonia since Arrhabaeus and other domestic detractors were convinced to lay down their arms and accept Perdiccas II as their suzerain lord.

[51] This proved to be a strategic error, since Argos quickly switched sides as a pro-Athenian democracy, allowing Athens to punish Macedonia with a naval blockade in 417 BC along with the resumption of military activity in Chalcidice.

[54] With improvements to military organization and building of new infrastructure such as fortresses, Archelaus was able to strengthen Macedonia and project his power into Thessaly, where he aided his allies; yet he faced some internal revolt as well as problems fending off Illyrian incursions led by Sirras.

[70] By 365 BC, Perdiccas III had reached the age of majority and took the opportunity to kill his regent Ptolemy, initiating a sole reign marked by internal stability, financial recovery, fostering of Greek intellectualism at his court, and the return of his brother Philip from Thebes.

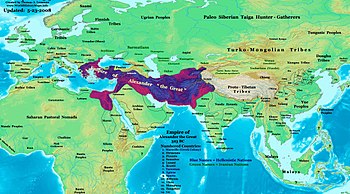

[71] Philip II of Macedon (r. 359 – 336 BC), who spent much of his adolescence as a political hostage in Thebes, was twenty-four years old when he acceded to the throne and immediately faced crises that threatened to topple his leadership.

[94] Meanwhile, Phocis and Thermopylae were captured, the Delphic temple robbers executed, and Philip II was awarded the two Phocian seats on the Amphictyonic Council as well as the position of master of ceremonies over the Pythian Games.

[101] After the Macedonian victory at Chaeronea, Philip II imposed harsh conditions on Thebes, installing an oligarchy there, yet was lenient to Athens due to his desire to utilize their navy in a planned invasion of the Achaemenid Empire.

[104] The Persian aid offered to Perinthus and Byzantion in 341–340 BC highlighted Macedonia's strategic need to secure Thrace and the Aegean Sea against increasing Achaemenid encroachment, as Artaxerxes III further consolidated his control over satrapies in western Anatolia.

[106] After his election by the League of Corinth as their commander-in-chief (strategos autokrator) of a forthcoming campaign to invade the Achaemenid Empire, Philip II sought to shore up further Macedonian support by marrying Cleopatra Eurydice, niece of general Attalus.

[110] Before Philip II was assassinated in the summer of 336 BC, relations with his son Alexander had degenerated to the point where he excluded him entirely from his planned invasion of Asia, choosing instead for him to act as regent of Greece and deputy hegemon of the League of Corinth.

[127] While utilizing effective propaganda such as the cutting of the Gordian Knot, he also attempted to portray himself as a living god and son of Zeus following his visit to the oracle at Siwah in the Libyan Desert (in modern-day Egypt) in 331 BC.

[145] Although Eumenes of Cardia managed to kill Craterus in battle, this had no grand effect on the course of events now that the victorious coalition convened in Syria to settle the issue of a new regency and territorial rights in the 321 BC Partition of Triparadisus.

[147] Forming an alliance with Ptolemy, Antigonus, and Lysimachus, Cassander had his officer Nicanor capture the Munichia fortress of Athens' port town Piraeus in defiance of Polyperchon's decree that Greek cities should be free of Macedonian garrisons, sparking the Second War of the Diadochi (319–315 BC).

[151] Cassander married Philip II's daughter Thessalonike, inducting him into the Argead dynastic house, and briefly extended Macedonian control into Illyria as far as Epidamnos, although by 313 BC, it was retaken by the Illyrian king Glaucias of Taulantii.

[153] Antigonus promptly allied with Polyperchon, now based in Corinth, and issued an ultimatum of his own to Cassander, charging him with murder for executing Olympias and demanding that he hand over the royal family, king Alexander IV and the queen mother Roxana.

[199] Rome responded by sending ten heavy quinqueremes from Roman Sicily to patrol the Illyrian coasts, causing Philip V to reverse course and order his fleet to retreat, averting open conflict for the time being.

[205] A year after the Aetolian League concluded a peace agreement with Philip V in 206 BC, the Roman Republic negotiated the Treaty of Phoenice, which ended the war and allowed the Macedonians to retain the settlements they had captured in Illyria.

[208] Although Rome's envoys played a critical role in convincing Athens to join the anti-Macedonian alliance with Pergamon and Rhodes in 200 BC, the comitia centuriata (i.e. people's assembly) rejected the Roman Senate's proposal for a declaration of war on Macedonia.

[210] Despite Philip V's nominal alliance with the Seleucid king, he lost the naval Battle of Chios in 201 BC and was subsequently blockaded at Bargylia by a combined fleet of the victorious Rhodian and Pergamene navies.

[212] With Carthage finally subdued following the Second Punic War, Bringmann contends that the Roman strategy changed from protecting southern Italy from Macedonia, to exacting revenge on Philip V for allying with Hannibal.

[215] When the comitia centuriata finally voted in approval of the Roman Senate's declaration of war and handed their ultimatum to Philip V by the summer of 200 BC, demanding that a tribunal assess the damages owed to Rhodes and Pergamon, the Macedonian king rejected it outright.

[216] Although the Macedonians were able to successfully defend their territory for roughly two years,[217] the Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus managed to expel Philip V from Macedonia in 198 BC with him and his forces taking refuge in Thessaly.

[219] Rome, dismissing the Aetolian League's demands to dismantle the Macedonian monarchy altogether, ratified a treaty that forced Macedonia to relinquish control of much of its Greek possessions, including Corinth, while allowing it to preserve its core territory, if only to act as a buffer against Illyrian and Thracian incursions into Greece.

[230] Although Eumenes II attempted to undermine these diplomatic relationships, Perseus fostered an alliance with the Boeotian League, extended his authority into Illyria and Thrace, and in 174 BC, won the role of managing the Temple of Apollo at Delphi in the Amphictyonic Council.

[234] Perseus fled to Samothrace but surrendered shortly afterwards, was brought to Rome for the triumph of Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, and placed under house arrest at Alba Fucens where he died in 166 BC.

[236] The Romans imposed severe laws inhibiting many social and economic interactions between the inhabitants of these respective republics, including the banning of marriages between them and the (temporary) prohibition on the use of Macedonia's gold and silver mines.