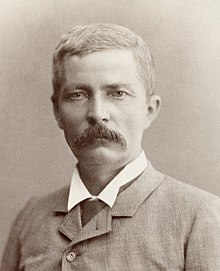

Henry Morton Stanley

Although he personally had high regard for many of the native African people who accompanied him on his expeditions,[3]: 10–11 the exaggerated accounts of corporal punishment and brutality in his books fostered a public reputation as a hard-driving, cruel leader,[3]: 201–202 in contrast to the supposedly more humanitarian Livingstone.

[6] As his parents were unmarried, his birth certificate describes him as a bastard; he was baptised in the parish of Denbigh on 19 February 1841, the register recording that he had been born on 28 January of that year.

34–41 Stanley reluctantly joined[12]: 50 in the American Civil War, first enrolling in the Confederate States Army's 6th Arkansas Infantry Regiment[13] and fighting in the Battle of Shiloh in 1862.

[20] Neither man mentioned it in any of the letters they wrote at this time,[3] and Livingstone tended to instead recount the reaction of his servant, Susi, who cried out: "An Englishman coming!

[21] Stanley biographer Tim Jeal argued that the explorer invented it afterwards to help raise his standing because of "insecurity about his background",[3]: 117 though ironically the phrase was mocked in the press for being absurdly formal for the situation.

[3]: 140 The Herald's own first account of the meeting, published 1 July 1872, reports:[22] Preserving a calmness of exterior before the Arabs which was hard to simulate as he reached the group, Mr. Stanley said: – "Doctor Livingstone, I presume?"

Between 1875 and 1876 Stanley succeeded in the first part of his objective, establishing that Lake Victoria had only a single outlet, the one discovered by John Hanning Speke on 21 July 1862 and named Ripon Falls.

[27] Stanley and his men reached the Portuguese outpost of Boma, around 100 kilometres (62 mi) from the mouth of the Congo River on the Atlantic Ocean, after 999 days on 9 August 1877.

Muster lists and Stanley's diary (12 November 1874) show that he started with 228 people[3]: 163, 511 note 21 and reached Boma with 114 survivors, with him the only European left alive out of four.

But neither the Foreign Office nor Edward, the Prince of Wales, felt called to receive Stanley after the many rumours of his looting and killing in the interior of the African continent.

[3]: 236 Stanley persuaded Leopold that the first step should be the construction of a wagon trail around the Congo rapids and a chain of trading stations on the river.

Building a road from Vivi to Isangila, Stanley took almost 2 years to traverse the rapids towing with him 50 tonnes of equipment, including 2 dismantled steamboats and a barge.

Tippu Tip had raided 118 villages, killed 4,000 Africans, and, when Stanley reached his camp, had 2,300 slaves, mostly young women and children, in chains ready to transport halfway across the continent to the markets of Zanzibar.

[citation needed] Having found the new ruler of the Upper Congo, Stanley had no choice but to negotiate an agreement with him, to stop Tip coming further downstream and attacking Leopoldville and other stations.

[40][citation needed] At the end of his physical resources, Stanley returned home, to be replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Francis de Winton, a former British Army officer.

[3] The spread of sleeping sickness across areas of central and eastern Africa that were previously free of the disease has been attributed to this expedition,[43][44] but this hypothesis has been disputed.

[3]: 437 He became Sir Henry Morton Stanley when he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the 1899 Birthday Honours, in recognition of his service to the British Empire in Africa.

His grave is in the churchyard of St Michael and All Angels' Church in Pirbright, Surrey, marked by a large piece of granite inscribed with the words "Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841–1904, Africa".

It can be translated as a term of endearment for, as the leader of Leopold's expedition, he commonly worked with the labourers breaking rocks with which they built the first modern road along the Congo River.

[3]: 241–242 Author Adam Hochschild suggested that Stanley understood it as a heroic epithet,[56]: 68 but there is evidence that Nsakala, the man who coined it, had meant it humorously.

[57][3]: 242 Having survived for ten years of his childhood in the workhouse at St Asaph, it is postulated that he needed as a young man to be thought of as harder and more formidable than other explorers.

"[68] In How I Found Livingstone (1872), he wrote that he was "prepared to admit any black man possessing the attributes of true manhood, or any good qualities ... to a brotherhood with myself.

[71] When Stanley first met a group of his Wangwana assistants, he was surprised: "They were an exceedingly fine looking body of men, far more intelligent in appearance than I could ever have believed African barbarians could be".

Stanley was charged with excessive violence, wanton destruction, the selling of labourers into slavery, the sexual exploitation of native women and the plundering of villages for ivory and canoes.

Kirk's report to the British Foreign Office was never published, but in it, he claimed: "If the story of this expedition were known it would stand in the annals of African discovery unequalled for the reckless use of power that modern weapons placed in his hands over natives who never before heard a gun fired.

[77] An American merchant in Zanzibar, Augustus Sparhawk, wrote that several of Stanley's African assistants, including Manwa Sera, "a big rascal and too fond of money", had been bribed to tell Kirk what he wanted to hear.

He wrote to the owner of the Daily Telegraph, insisting that he (Lawson) force the British government to send a warship to take the Wangwana home to Zanzibar and to pay all their back wages.

[80] Stanley's hatred of the promiscuity that had caused his illegitimacy and his legendary shyness with women, made the Kirk report's claim that he had accepted an African mistress offered to him by Kabaka Mutesa exceedingly implausible.

[90] John Rose Troup, in his book about the Emin Pasha expedition, said that he saw Stanley's self-serving and vindictive side: "In the forgoing letter he brings forward disgraceful charges, that really do not refer to me at all, although he blames me for what happened.

"[95] The legacy of death and destruction in the Congo region during the Free State period and the fact that Stanley had worked for Leopold are considered by author Norman Sherry to have made him an inspiration for Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness.