Herbal medicine

[3][4] There is limited scientific evidence for the safety and efficacy of many plants used in 21st-century herbalism, which generally does not provide standards for purity or dosage.

[6] Paraherbalism describes alternative and pseudoscientific practices of using unrefined plant or animal extracts as unproven medicines or health-promoting agents.

[1][5][7][8] Paraherbalism relies on the belief that preserving various substances from a given source with less processing is safer or more effective than manufactured products, a concept for which there is no evidence.

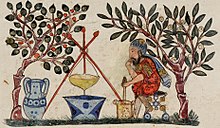

Written evidence of herbal remedies dates back over 5,000 years to the Sumerians, who compiled lists of plants.

[11] Seeds likely used for herbalism were found in archaeological sites of Bronze Age China dating from the Shang dynasty[12] (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BCE).

[14] De Materia Medica, originally written in Greek by Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40 – c. 90 CE) of Anazarbus, Cilicia, a physician and botanist, is one example of herbal writing used over centuries until the 1600s.

[19] In the United States, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health funds clinical trials on herbal compounds, provides fact sheets evaluating the safety, potential effectiveness and side effects of many plant sources,[20] and maintains a registry of clinical research conducted on herbal products.

[22][23][24] Multiple factors such as gender, age, ethnicity, education and social class are also shown to have associations with the prevalence of herbal remedy use.

[25] There are many forms in which herbs can be administered, the most common of which is a liquid consumed as a herbal tea or a (possibly diluted) plant extract.

[36] Furthermore, "adulteration, inappropriate formulation, or lack of understanding of plant and drug interactions have led to adverse reactions that are sometimes life threatening or lethal.

[39] Standardization of purity and dosage is not mandated in the United States, but even products made to the same specification may differ as a result of biochemical variations within a species of plant.

[41] They are not marketed to the public as herbs, because the risks are well known, partly due to a long and colorful history in Europe, associated with "sorcery", "magic" and intrigue.

[53] In a 2018 study, the FDA identified active pharmaceutical additives in over 700 analyzed dietary supplements sold as "herbal", "natural" or "traditional".

Researchers at the University of Adelaide found in 2014 that almost 20 percent of herbal remedies surveyed were not registered with the Therapeutic Goods Administration, despite this being a condition for their sale.

[55] In 2015, the New York Attorney General issued cease and desist letters to four major U.S. retailers (GNC, Target, Walgreens, and Walmart) who were accused of selling herbal supplements that were mislabeled and potentially dangerous.

[58] In the United Kingdom, the training of herbalists is done by state-funded universities offering Bachelor of Science degrees in herbal medicine.

[61][62][63] During the COVID-19 pandemic, the FDA and U.S. Federal Trade Commission issued warnings to several hundred American companies for promoting false claims that herbal products could prevent or treat COVID-19 disease.

[8][72] Presumed claims of therapeutic benefit from herbal products, without rigorous evidence of efficacy and safety, receive skeptical views by scientists.

It relies on the false belief that preserving the complexity of substances from a given plant with less processing is safer and potentially more effective, for which there is no evidence either condition applies.

[78] In Andean healing practices, the use of entheogens, in particular the San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi) is still a vital component, and has been around for millennia.

[79] Some researchers trained in both Western and traditional Chinese medicine have attempted to deconstruct ancient medical texts in the light of modern science.

In 1972, Tu Youyou, a pharmaceutical chemist and Nobel Prize winner, extracted the anti-malarial drug artemisinin from sweet wormwood, a traditional Chinese treatment for intermittent fevers.

[84] In Indonesia, especially among the Javanese, the jamu traditional herbal medicine may have originated in the Mataram Kingdom era, some 1300 years ago.

[86] The Madhawapura inscription from Majapahit period mentioned a specific profession of herb mixer and combiner (herbalist), called Acaraki.

[88] Although primarily herbal, some Jamu materials are acquired from animals, such as honey, royal jelly, milk, and Ayam Kampung eggs.

[89][90] Indigenous healers often claim to have learned by observing that sick animals change their food preferences to nibble at bitter herbs they would normally reject.

[91] Field biologists have provided corroborating evidence based on observation of diverse species, such as chickens, sheep, butterflies, and chimpanzees.