Hexamethylbenzene

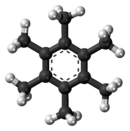

In 1929, Kathleen Lonsdale reported the crystal structure of hexamethylbenzene, demonstrating that the central ring is hexagonal and flat[1] and thereby ending an ongoing debate about the physical parameters of the benzene system.

[20] Hexamethylbenzene is sometimes called mellitene,[20] a name derived from mellite, a rare honey-coloured mineral (μέλι meli (GEN μέλιτος melitos) is the Greek word for honey.

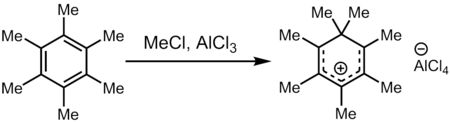

Conversely, mellitene can be oxidised to form mellitic acid:[4] Treatment of hexamethylbenzene with a superelectrophilic mixture of methyl chloride and aluminum trichloride (a source of Meδ⊕Cl---δ⊖AlCl3) gives heptamethylbenzenium cation, one of the first carbocations to be directly observed.

[3] Lonsdale described the work in her book Crystals and X-Rays,[25] explaining that she recognised that, though the unit cell was triclinic, the diffraction pattern had pseudo-hexagonal symmetry that allowed the structural possibilities to be restricted sufficiently for a trial-and-error approach to produce a model.

[3] This work definitively showed that hexamethylbenzene is flat and that the carbon-to-carbon distances within the ring are the same,[2] providing crucial evidence in understanding the nature of aromaticity.

[35][36] In 1880, Joseph Achille Le Bel and William H. Greene reported[37] what has been described as an "extraordinary" zinc chloride-catalysed one-pot synthesis of hexamethylbenzene from methanol.

[38] At the catalyst's melting point (283 °C), the reaction has a Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of −1090 kJ mol−1 and can be idealised as:[38] Le Bel and Greene rationalised the process as involving aromatisation by condensation of methylene units, formed by dehydration of methanol molecules, followed by complete Friedel–Crafts methylation of the resulting benzene ring with chloromethane generated in situ.

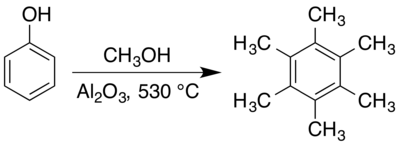

[32] An Organic Syntheses preparation, using methanol and phenol with an alumina catalyst at 530 °C, gives approximately a 66% yield,[21] though synthesis under different conditions has also been reported.

Valentin Koptyug and co-workers found that both hexamethylcyclohexadienone isomers (2,3,4,4,5,6- and 2,3,4,5,6,6-) are intermediates in the process, undergoing methyl migration to form the 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexamethylbenzene carbon skeleton.

[6] The electron-donating nature of the methyl groups—both that there are six of them individually and that there are six meta pairs among them—enhance the basicity of the central ring by six to seven orders of magnitude relative to benzene.

[48] Examples of such complexes have been reported for a variety of metal centres, including cobalt,[49] chromium,[35] iron,[7] rhenium,[50] rhodium,[49] ruthenium,[8] and titanium.

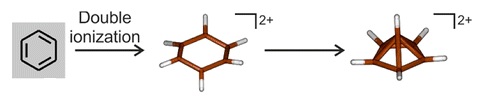

[54] In the early 1970s theoretical work led by Hepke Hogeveen predicted the existence of a pyramidal dication C6(CH3)2+6, and the suggestion was soon supported by experimental evidence.

The preparation method involved treating the epoxide of hexamethyl Dewar benzene with magic acid, which formally abstracts an oxide anion (O2−) to form the dication:[9] Though indirect spectroscopic evidence and theoretical calculations previously pointed to their existence, the isolation and structural determination of a species with a hexacoordinate carbon bound only to other carbon atoms is unprecedented,[9] and has attracted comment in Chemical & Engineering News,[11] New Scientist,[10] Science News,[12] and ZME Science.

[14] This satisfies the octet rule by binding a carbon(IV) centre (C4+) to an aromatic η5–pentamethylcyclopentadienyl anion (six-electron donor) and methyl anion (two-electron donor), analogous to the way the gas-phase organozinc monomer [(η5–C5(CH3)5)Zn(CH3)], having the same ligands bound to a zinc(II) centre (Zn2+) satisfies the 18 electron rule on the metal.

Left : n = 2, [Ru II (η 6 -C 6 (CH 3 ) 6 ) 2 ] 2+

Right : n = 0, [Ru 0 (η 4 -C 6 (CH 3 ) 6 )(η 6 -C 6 (CH 3 ) 6 )]

Methyl groups omitted for clarity. The electron-pairs involved with carbon–ruthenium bonding are in red.

6 (CH

3 ) 2+

6

6 (CH

3 ) 2+

6 having a rearranged pentagonal-pyramid framework