Egyptian hieroglyphs

[5] Egyptian hieroglyphs are the ultimate ancestor of the Phoenician alphabet, the first widely adopted phonetic writing system.

[7] During the 5th century, the permanent closing of pagan temples across Roman Egypt ultimately resulted in the ability to read and write hieroglyphs being forgotten.

Despite attempts at decipherment, the nature of the script remained unknown throughout the Middle Ages and the early modern period.

The most complete compendium of Ancient Egyptian, the Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache, contains 1.5–1.7 million words.

The glyphs themselves, since the Ptolemaic period, were called τὰ ἱερογλυφικὰ [γράμματα] (tà hieroglyphikà [grámmata]) "the sacred engraved letters", the Greek counterpart to the Egyptian expression of mdw.w-nṯr "god's words".

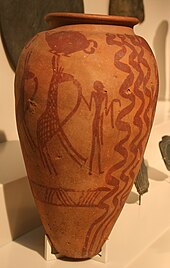

[6] The first full sentence written in mature hieroglyphs so far discovered was found on a seal impression in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen at Umm el-Qa'ab, which dates from the Second Dynasty (28th or 27th century BC).

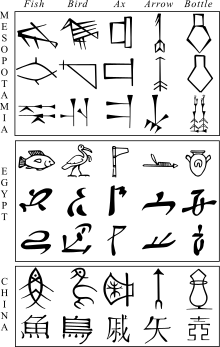

[24][25] Further, Egyptian writing appeared suddenly, while Mesopotamia had a long evolutionary history of the usage of signs—for agricultural and accounting purposes—in tokens dating as early back to c. 8000 BC.

However, more recent scholars have held that "the evidence for such direct influence remains flimsy" and that "a very credible argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt..."[26] While there are many instances of early Egypt-Mesopotamia relations, the lack of direct evidence for the transfer of writing means that "no definitive determination has been made as to the origin of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt".

[27] Since the 1990s, the above-mentioned discoveries of glyphs at Abydos, dated to between 3400 and 3200 BCE, have shed further doubt on the classical notion that the Mesopotamian symbol system predates the Egyptian one.

Hieroglyphs continued to be used under Persian rule (intermittent in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE), and after Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt, during the ensuing Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

It appears that the misleading quality of comments from Greek and Roman writers about hieroglyphs came about, at least in part, as a response to the changed political situation.

[7] Monumental use of hieroglyphs ceased after the closing of all non-Christian temples in 391 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I; the last known inscription is from Philae, known as the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom, from 394.

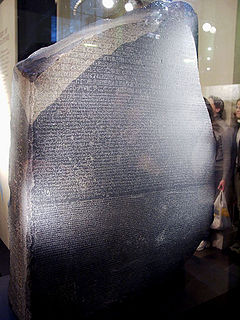

[32] All medieval and early modern attempts were hampered by the fundamental assumption that hieroglyphs recorded ideas and not the sounds of the language.

Kircher was familiar with Coptic, and thought that it might be the key to deciphering the hieroglyphs, but was held back by a belief in the mystical nature of the symbols.

In the early 19th century, scholars such as Silvestre de Sacy, Johan David Åkerblad, and Thomas Young studied the inscriptions on the stone, and were able to make some headway.

In his Lettre à M. Dacier (1822), he wrote: It is a complex system, writing figurative, symbolic, and phonetic all at once, in the same text, the same phrase, I would almost say in the same word.

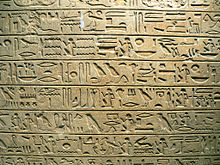

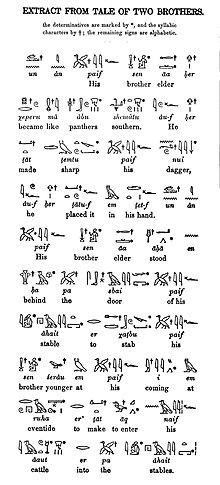

[34]Visually, hieroglyphs are all more or less figurative: they represent real or abstract elements, sometimes stylized and simplified, but all generally perfectly recognizable in form.

It is also possible to use the hieroglyph of the pintail duck without a link to its meaning in order to represent the two phonemes s and ꜣ, independently of any vowels that could accompany these consonants, and in this way write the word: sꜣ, "son"; or when complemented by other signs detailed below[clarification needed] sꜣ, "keep, watch"; and sꜣṯ.w, "hard ground".

The Egyptian hieroglyphic script contained 24 uniliterals (symbols that stood for single consonants, much like letters in English).

Ancient Egyptian scribes consistently avoided leaving large areas of blank space in their writing and might add additional phonetic complements or sometimes even invert the order of signs if this would result in a more aesthetically pleasing appearance (good scribes attended to the artistic, and even religious, aspects of the hieroglyphs, and would not simply view them as a communication tool).

For example, the symbol of "the seat" (or chair): Finally, it sometimes happens that the pronunciation of words might be changed because of their connection to Ancient Egyptian: in this case, it is not rare for writing to adopt a compromise in notation, the two readings being indicated jointly.

Besides a phonetic interpretation, characters can also be read for their meaning: in this instance, logograms are being spoken (or ideograms) and semagrams (the latter are also called determinatives).

Here, are several examples of the use of determinatives borrowed from the book, Je lis les hiéroglyphes ("I am reading hieroglyphs") by Jean Capart, which illustrate their importance: – nfrw (w and the three strokes are the marks of the plural): [literally] "the beautiful young people", that is to say, the young military recruits.

These signs have, however, a function and existence of their own: for example, a forearm where the hand holds a scepter is used as a determinative for words meaning "to direct, to drive" and their derivatives.

As of July 2013[update], four fonts, Aegyptus, NewGardiner, Noto Sans Egyptian Hieroglyphs and JSeshFont support this range.

Another font, Segoe UI Historic, comes bundled with Windows 10 and also contains glyphs for the Egyptian Hieroglyphs block.

Segoe UI Historic excludes three glyphs depicting phallus (Gardiner's D52, D52A D53, Unicode code points U+130B8–U+130BA).