High-velocity cloud

High-velocity clouds (HVCs) are large accumulations of gas with an unusually rapid motion relative to their surroundings.

This was quite notable because the models of the Milky Way showed the density of gas decreasing with distance from the galactic plane, rendering this a striking exception.

According to the prevailing galactic models, the dense pockets should have dissipated long ago, making their very existence in the halo quite puzzling.

In 1956 the solution was proposed that the dense pockets were stabilized by a hot, gaseous corona that surrounds the Milky Way.

In 1997, a map of the Milky Way's neutral hydrogen was largely complete, again allowing astronomers to detect more HVCs.

In the late 1990s, using data from the La Palma Observatory in the Canary Islands, the Hubble Space Telescope, and, later, the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE), the distance to an HVC was gauged for the first time.

HVCs are defined by their respective velocities, but distance measurements allow for estimates on their size, mass, volume density, and even pressure.

Halo stars that have been identified through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey have led to distance measurements for almost all of the large complexes currently known.

One indirect method involves Hα observations, where an assumption is made that the emission lines come from ionizing radiation from the galaxy, reaching the cloud's surface.

Observations have shown that HVCs can have ionized exteriors due to external radiation or the motion of the HVC through a diffuse halo medium.

Typically, high resolution observations eventually show that larger HVCs are often composed of many smaller complexes.

[1] Cold clouds moving through a diffuse halo medium are estimated to have a survival time on the order of a couple hundred million years without some sort of support mechanism that prevents them from dissipating.

The multi-phase structure of the gaseous halo suggests that there is an ongoing life-cycle of HVC destruction and cooling.

This process works due to the HVC having a cold neutral interior shielded by a warmer and lower-density exterior, causing the HI clouds to have smaller relative velocities with respect to their surroundings.

Jan Oort developed a model to explain HVCs as gas left over from the early formation of the galaxy.

Given an isolated galaxy (i.e. one without ongoing assimilation of hydrogen gas), successive generations of stars should infuse the Interstellar Medium (ISM) with higher abundances of heavy elements.

HVCs may explain these observations by representing a portion of the primordial gas responsible for continuously diluting the ISM.

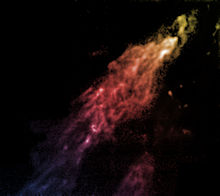

[1] Evidence for this model of HVC formation comes from observations of the Magellanic Stream in the halo of the Milky Way.

[1] Another model, proposed by David Eichler, now at Ben Gurion University, and later by Leo Blitz of the University of California at Berkeley, assumes the clouds are very massive, located between galaxies, and created when baryonic material pools near concentrations of dark matter.

The Milky Way has approximately 5 billion solar masses of star forming material within its disk and a SFR of 1–3

[1] Models for galactic chemical evolution find that at least half of this amount must be continuously accreted, low-metallicity material to describe the current, observable structure.

The current model for the universe, ɅCDM, indicates that galaxies tend to cluster and achieve a web-like structure over time.

70% of the mass inflow at the virial radius is consistent with coming in along cosmic filaments in evolutionary models of the Milky Way.

Gas of this type, detectable out to ~160,000 ly (50 kpc), largely becomes part of the hot halo, cools and condenses, and falls into the Galactic disk to serve in star formation.

X-ray and gamma-ray observations in the Milky Way indicate the likelihood of some central engine feedback having occurred in the past 10–15 megayears (Myr).

Furthermore, as described in “origins,” the disk-wide “galactic fountain” phenomenon is similarly crucial in piecing together the Milky Way's evolution.

[1] Likewise detailed in the "origins" section, satellite accretion plays a role in the evolution of a galaxy.

[2] These measurements have led scientists to believe that Complex C has begun to mix with other, younger, nearby gas clouds.

The other half of the gas (the leading arm component) was accelerated and pulled out in front of the galaxies in their orbit.

Smith's Cloud is another well-studied HVC found in the Southern Hemisphere, located in the constellation Aquila.